Abstract

This white paper discusses a model of best practices to better identify and address plagiarism issues with students using AI. It serves as an example to help younger institutions that may not have a policy in place to recognize the importance of hitting this head-on. By creating a taskforce, we were able to quickly come to a resolution for a university that has three campuses in Chicago, Online, and in Vancouver, BC. We also share best practices that will help current professors and core faculty alike in dealing with plagiarism from students using AI in their work. We end with a discussion of examples that support this effort.

Keywords: AI, plagiarism, model of best practices, Turnitin, Grammarly, and training.

Artificial Intelligence and Plagiarism

For most universities, plagiarism is nothing new. It has been an issue for students since the first paper was submitted. Universities have academic honesty policies in place to help combat the use of plagiarism; however, it is a battle that will likely never end. In fact, the more advanced the world's technology gets, the easier it will be for students to plagiarize. Luckily, as the technology grows, so do the tools used to recognize plagiarism. This paper will outline an academic institution's journey in recognizing and training students on academic integrity at the height of artificial intelligence (AI) being used by students.

Background

Turnitin is not a new tool, and universities have been using it for years. While it is not the only tool used to detect plagiarism on campuses, Turnitin is the more popular choice (Alkhaqani, 2023). The tool has many benefits for professors and students alike. It is designed to capture the integrity of the student, but it also provides them with a space to learn and become better writers (Gutierrez-Aguilar et al., 2023; Siswanto et al., 2024). However, it is suggested that universities need to do better jobs with training initiatives for students when using Turnitin (Nketsiah, Imoro, & Barfi, 2023). Some institutions also reported that most students do not even know what the tool is, how it is used, nor are they aware of the academic honesty policy of their respective campus (Alua, Asiedu, & Bumbie-Chi, 2023; Ismail, & Jabri, 2023).

Institutional instructors use Turnitin for a variety of reasons. For some, it has become more than just an integrity tool; it has also led to better feedback for students regarding other high-level issues in the student pepare (Laflen, 2023). These features include GradeMark and PeerMark (Li,2018; Li, 2017). It has been reported that using these features increases critical thinking abilities in students (Alharbi, & Al-Hoorie, 2020). Instructors could also see how students used their comments and made the suggested changes to their papers. While this feature is convenient for instructors, it is not the most user-friendly for students to navigate (Laflen, 2023).

It is important to note that while blatant plagiarizing should not be tolerated in higher education, it is not always intentional (Koca, Pekdağ, & Gezgin, 2023). It could be due to "poor research and citation skills" (Meo & Talha, 2019, p.48).

"Mukasa et al. (2023) report that "lack of interest" could be the cause along with "lack of preparation and effort, low self-efficacy, poor studying techniques, and convenience of internet sources"; pressure of time with competing priorities," such as "misplaced priorities, procrastination, high workloads, poor planning, competing interests, and the perception of availability of time at the start of the semester"; and "lack of understanding of the policy on academic honesty," such as "lack of awareness of plagiarism, lack of awareness of acceptable similarity, conflicting messages from tutors and confusion with high school learning" (p.1) are the reasons" (Koca, Pekdağ, & Gezgin, 2023, p. 250).

Institutions of higher education are now having to fight against AI (Perkins et al., 2024). Now that AI is becoming more prevalent, so are the tools that are used to detect it in student writing; however, there is still much work to do in this area as technology is growing faster than plagiarism tools, such as Turnitin, can update and reevaluate how it is capturing this data (Elkhatat, Elsaid, & Almeer, 2023). There are some reports of students being able to go around this new technology by spending more time with their AI software by adding more keywords and outlining the paper for the AI program (Foster, 2023). The good thing is that it takes more effort to do this than to just write the paper itself. Interestingly, universities are not the only ones struggling with this new technology, as academic journals also take great strides in capturing AI content before work reaches the publication phase (Hu, 2023).

It is noted that universities worldwide are taking strides and sides with using AI in the classroom (Ogwueleka, 2025; Safi, R. 2025). Some universities are reporting updates to their academic honesty policy to uphold the integrity and policies of their institution, while others are relaxing their policies to make room for AI and the next generation of students (Safi, 2025). There are fair arguments on both sides of the debate. Most universities seem unsure how to approach this new technology (Singh, & Kaur, 2025). With higher education in the balance, it will be crucial for universities to take a stance on the issue. This one decision can potentially change academia forever (Rasheed, in press).

Defining Turnitin and Grammarly

Turnitin has become a gold standard for most institutions of higher learning in the United States; however, not everyone is familiar with it. This tool was created back in 1998 by graduate students. What started as a peer-review application became the most sought-after tool for plagiarism and feedback. It is the most recognizable and trusted software on the market today, and it is used to detect plagiarism from many sources (Obeng-Ofori, & Adaobi, 2025).

Grammarly, which was created in 2009, has become increasingly popular with students and has been largely adopted by most universities across the United States and beyond. Grammarly is an auto-proof reading system used to identify numerous grammatical rules. This tool can also give substantial feedback for many writing (ONiell, & Russel, 2019). Grammarly can be used as a plagiarism checker, and newly released its AI software in 2023.

Trusting AI Detection Software

Knowing the devastating and extensive consequences of AI in academic writing, some institutions are still weary of using the new AI tool for plagiarism, fearing that it puts students at a disadvantage (Gooch et al., 2024; Walters, 2023). This comes from not knowing exactly how Turnitin is capturing this data with the anxiety that high plagiarism scores using the AI feature could lead to misunderstandings and dismal of students who did not intentionally plagiarize. This is a notable concern due to the fact this technology is new and still in the pilot phase. There are significant differences between GPT-3.5 and GPT-4.0 in terms of how accurately the AI detection works (Walters, 2023). It is reported that AI detection from sources like GPT-3.5 is very accurate; however, using GPT 4.0 the AI detection is less precise (Walters, 2023). Either way, the paid version that most universities use has been shown to be more accurate and precise than their free counterparts (Walters, 2023). Perkins et al., 2023 indicated in their research that AI tools like Turnitin are very reliable in capturing AI-generated content. While the software is not perfect, the errors do not seem to be labeling something incorrectly as AI content; rather, they are not labeling them at all. This indicates that more work needs to be performed on GPT-4.0 and how detection software, such as Turnitin, performs.

Grammarly vs. Turnitin

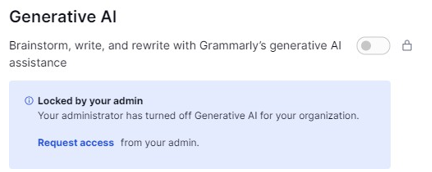

In recent months, there has been a lot of discussion online about how Grammarly may be detected as AI using Turnitin (Ding & Zou, 2024). This is a problem because many universities pay to use both applications to help improve students' writing (Ashrafganjoe, Rezai, & Elhambakhsh, 2022). While Grammarly does use AI, it only uses generative AI if the administrator turns that feature on. Grammarly has three options: Grammarly basic-free version, GrammarlyPro-paid version, and GrammarlyGo-A.I. feature (Fitria, 2021; Natale, 2023; Turnitin, 2023). GrammarlyGo is used in both the free and the Pro versions, and yes, if students use this feature, it will show as plagiarized using Turnitin. It is important to note that most institutions turn this feature off (figure 2). However, students can still use the free version on their own. It is also worth nothing if students use the plagiarism checker in Grammarly; Turnitin will also flag their work because this feature in Grammalry uses AI for that technology.

The Model

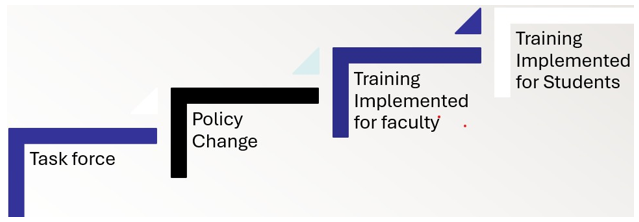

Recognizing the dangers of students using AI in their work, Alder University created a model of best practices (Figure 1). Our purpose was not to go after students with more rules and regulations but rather to protect the integrity of the institution and all the stakeholders it harbors. We took great care to ensure our efforts reflected our institution's values and mission. This process was a collaborative effort by faculty from different university campuses from Chicago, Vancouver, and Online; we also had legal counsel involved in the process.

Figure 1: Model for Academic Honesty Policy Change

GPT Taskforce

Our task force was made up of 13 faculty members, including legal counsel from different departments on all three campuses. The Online campus being 100% virtual, the Chicago campus, and the Vancouver campus, which is outside the U.S., shows the global ramifications of this work. We were tasked to look at the current policy and evaluate if any changes needed to be made to serve our community better. Each member of the task force was able to make notes on the current academic honesty policy. After weeks of deliberation, we decided our students would be better served with a strict yet broad scope of AI usage to encounter AI from a including but not limited to ChatGPT.

Policy Change

The Academic Honesty Policy Change was finalized by the task force and sent out to all three faculty councils for a vote. Each respective council was able to vote in favor of, approved with changes, or not in favor of. In our case, all three councils on the Chicago, Vancouver, and Onlin ecampuses agreed in favor of the changes and the new policy was implemented in the Spring term of 2024 (appendix A).

Examples of those changes are:

"Copying material and/or using ideas from an article, book, unpublished paper, or any material or source found on the Internet without proper documentation of references and citations, or without properly enclosing quoted material in quotation marks. This includes material retrieved from or generated by artificial intelligence tools, including but not limited to ChatGPT" (Adler University, 2024, paragraph B1)

"Substantial utilization of the published or unpublished work of others without permission, citation, or credit—also known as "cut and paste" or "patch writing" and including works retrieved from or generated by artificial intelligence tools such as but not limited to ChatGPT; and/or" (Adler University, 2024, paragraph B4).

Training Implemented for Faculty

During this process, we realized that several of our faculty members do not grasp the importance of this policy, nor do they use the Turnitin tool provided by the institution effectively. To resolve this issue, we contacted our vendor at Turnitin, who was able to conduct a series of training sessions for our faculty. The vendor was able to show all the current and new to show all the current and new features of the tool while paying special attention to AI detection. Seasoned faculty who were aware of how the tool worked and functioned also aided in the training. We were not able to formally capture the effectiveness of this training in this paper; however, we are working on other scholarship that will showcase how this training was instrumental for faculty development.

Training implemented for Students

We took special care in training faculty so that they could be training ambassadors for students. Training took place in both synchronized sessions with students as well as 1x1. It was important for faculty to remind students not to use any other program to help them write their papers other than what is approved by the institution. In our case, Grammarly is approved to help their writing as our professional version does not use AI, such as GrammarlyGo. Our admin staff turned this feature off (figure 2). Turnitin will flag it as plagiarized if students use a different version of Grammarly with the feature below turned on. The impact of this training was noticed immediately by the faculty who implemented it in their classroom. We will show this data in our next paper.

Figure 2: GrammarlyGo Turned Off by School Admin

Best Practices

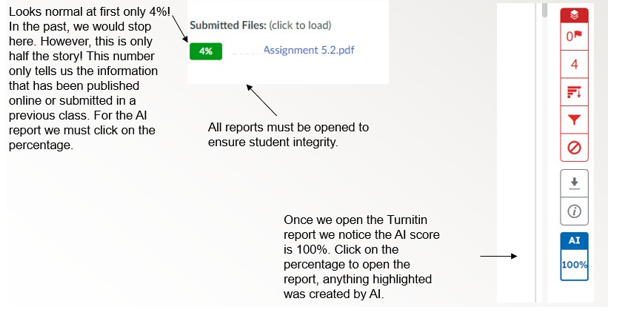

During the training, some core faculty determined some best practices for using the Turnitin tool. For some faculty, it was an easy zero on an assignment; however, we asked them to look at it as a training tool for new students. As an institution, we set the boundaries for the main Turnitin score to 20% and the AI score to 30%. Anything over these percentages needs an investigation to determine if the student plagiarized any work. The 20% for the main score is the norm for most academic institutions; however, since AI is so new, we use the 30% threshold to give us some wiggle room for error. However, no specific criteria were used to come up with these thresholds. Remember, these are two different scores; one score does not affect the other (figure 3).

Figure 3: Difference in Scores, still plagiarism

It is Plagiarism. Now What?

After determining whether the student has committed some sort of plagiarism, it is best to meet them where they are, especially for the first offense. Of course, all faculty members have the academic freedom to grade however they deem appropriate. We hope they will consider other methods before handing out zeros, namely due to the issues expressed earlier in the paper. It is well documented that some students do it unintentionally. Set up a meeting with the students and probe where they got this information. We have heard many students say they have used Grammarly, but we know that if the student used the institutional version of Grammarly, that would not be an issue. So either they are going off on their own using a different version of Grammarly, or there is more to the story. More often than not, they will confess to the program they used. (e.g., A student used a tool other than Turnitin that was supposed to check for plagiarism; while the student thought they were doing the right thing, the tool reworked the paper, added several more citations and references, and rephrased much of their work). That example paper is shown in Figure 3.

As you can see, the main score was strong 4%, with a 100% AI score. Instead of giving the student a zero, the professor allowed the student to redo the work on their own and resubmit through Turnitin. Instead of this becoming a disastrous situation for that student, they walked away with better skills to do the next assignment. As mentioned above, because students can create free accounts and still use the generative AI feature in Grammarly, they should be encouraged to use only their institutional-approved resources, which they must sign into their school accounts to access. If they do not, it is likely to be flagged as plagiarism.

Students should get a copy of the academic honesty policy at the beginning of every course. Have quick conversations about what this means for them, and use this time to talk about AI and the dangers of using it in their work. Have a planned course of action for students who commit plagiarism of any kind. Step 1. Students get a zero. Step 2. Ask the student to set up a meeting with you to discuss. Step 3. Give the student the option to redo the work if it's the first offense. Step 4. Have a plan in place if the student does it again; this step should align with the institution's plan for plagiarism. You will want to have a way to track students through each course. Students often get a clean slate once they get a new professor. If they plagiarize in one course, they are likely to do it in another. Institutions can have a plagiarism committee or send students to a student's comprehensive evaluation committee. For this to work, all plagiarism issues need to be documented and moved with the student. Faculty should know that student (A) has had a plagiarism accusation against them; however, the student was mentored, and the grade was corrected. Institutions will have to decide how many attempts students should get before being dismissed from the program.

Discussion

Why do we care about AI in students' work? After all, it is the new norm. Unfortunately, many members of the academic community ask this question. One way to look at this is from this example: A member from the community was noted for their exemplary work on their recent publication, and they were set to receive a prestigious award that is given to the top authors in the journal, right before the award was handed out the committee noticed that paper was completely written by AI. Do we still award the recipient? While this example may lead to an easy conclusion, we ask ourselves why we are rewarding students for the same behavior. Does the student get an "A" grade?

Another situation involved a student who chose to write a paper in their own native language, in this case, Mandarin. The student then used AI to translate their work into English. Turnitin caught it and flagged it as AI 100%. The Student Comprehensive Evaluation Committee (SCEC) discussed the situation with faculty on both sides of the argument. Being a social justice-minded institution, some thought the student should be able to write in their own language, and at first glance, it makes sense to come to that conclusion. However, we realized several things. To attend the university, students must prove they can read and speak in English; it is common practice for students outside of English-speaking countries to take the Test of English as Foreign Language (TOEFL) assessment. We also wondered if the student used AI during the admission process. We were looking at the long-term ramifications of allowing students to do this. What happens when these students get hired by an English-speaking company and the company realizes the applicant cannot read or write in English?

Suppose one university does not take plagiarism seriously, whether AI or something else; it affects all institutions of higher learning. We have a responsibility to uphold the integrity of academia. This comes at a time when potential students are doubting the skills and comprehensive education that institutes of higher education offer. The next generation is weighing the cost of attending a university against the future workforce they may find themselves in, which AI will primarily control in the next several years. Policymakers will likely face resistance from some faculty members who believe that AI is the future for the next generation and that putting limitations on it will deter students. On either side, this choice will lead to these two possible outcomes: A university of high ethical standards whose degree- granting institution means something or a paper mill that only cares about the bottom line.

We took great care to ensure we represented and reported everything accurately with Turnitin, Grammarly, and other tools in this white paper. It's important to note that technology is changing every day. What might be the reality now may not be tomorrow. If you're a faculty member at a university, it is always best to check with your current administrators on best practices and policies when dealing with plagiarism in any form.

List of abbreviations:

Artificial Intelligence (AI), Student Comprehensive Evaluation Committee (SCEC), Test of English as Foreign Language (TOEFL)

References

Alharbi, M. A., & Al-Hoorie, A. H. (2020). Turnitin peer feedback: controversial vs. non- controversial essays. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 17(1), 17.

Alkhaqani, A. L. (2023). ChatGPT and Future of Medical Research Writing, J of med & Clin Nursing & Health 1 (1), 01-04.

Alua, M. A., Asiedu, N. K., & Bumbie-Chi, D. M. (2023). Students' perception on plagiarism and usage of turnitin anti-plagiarism software: the role of the library. Journal of Library Administration, 63(1), 119-136.

Ashrafganjoe, M., Rezai, M. J., & Elhambakhsh, S. E. (2022). Providing computer-based feedback through Grammarly® in writing classes. Journal of Language and Translation, 12(2), 163-176.

Ding, L., & Zou, D. (2024). Automated writing evaluation systems: A systematic review of Grammarly, Pigai, and Criterion with a perspective on future directions in the age of generative artificial intelligence. Education and Information Technologies, 1-53.

Elkhatat, A. M., Elsaid, K., & Almeer, S. (2023). Evaluating the efficacy of AI content detection tools in differentiating between human and AI-generated text. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 19(1), 17.

Foster, A. (2023). Can GPT-4 Fool TurnItIn? Testing the Limits of AI Detection with Prompt Engineering. Presentation at Kenyon College.

Fitria, T. N. (2021). Grammarly as AI-powered English writing assistant: Students' alternative for writing English. Metathesis: Journal of English Language, Literature, and Teaching, 5(1), 65-78.

Gooch, D., Waugh, K., Richards, M., Slaymaker, M., & Woodthorpe, J. (2024). Exploring the Profile of University Assessments Flagged as Containing AI-Generated Material. ACM Inroads, 15(2), 39-47.

Gutierrez-Aguilar, O., Huarsaya-Rodriguez, E., Torres de Manchego, V., & Duche-Pérez, A. (2023, November). Predictors of Academic Satisfaction Through Activities with Turnitin. In XVIII Multidisciplinary International Congress on Science and Technology (pp. 327- 338). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

Hu, G. (2023). Challenges for enforcing editorial policies on AI-generated papers. Accountability in Research, 1-3.

Ismail, I., & Jabri, U. (2023). Academic integrity: Preventing students' plagiarism with Turnitin. Edumaspul: Jurnal Pendidikan, 7(1), 28-38.

Koca, Ş., Pekdağ, B., & Gezgin, U. B. (2023). Turnitin, plagiarism, AI similarity index and AI-generated content: a discussion.

Laflen, A. (2023). Exploring how response technologies shape instructor feedback: A comparison of Canvas Speedgrader, Google Docs, and Turnitin GradeMark. Computers and composition, 68, 102777.

Li, M. (2018). Online peer review using Turnitin PeerMark. Journal of Response to Writing, 4(2), 99–117.

Li, M., & Li, J. (2017). Online peer review using Turnitin in first-year writing classes. Computers and Composition, 46, 2138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2017.09.001.

Meo, S. A., & Talha, M. (2019). Turnitin: Is it a text matching or plagiarism detection tool?. Saudi journal of anaesthesia, 13(Suppl 1), S48.

Mukasa, J., Stokes, L., & Mukona, D. M. (2023). Academic dishonesty by students of bioethics at a tertiary institution in Australia: An exploratory study. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 19(1), 1-15.

Natale, N. (2023). A-Literacy and Digital Orality: A Figure/Ground Relation for Our Digital Dilemma. New Explorations: Studies in Culture and Communication, 3(2).

Nketsiah, I., Imoro, O., & Barfi, K. A. (2023). Postgraduate students' perception of plagiarism, awareness, and use of Turnitin text-matching software. Accountability in Research, 1-17.

Obeng-Ofori, D., & Adaobi, C. C. (2025). Understanding Turnitin: A Comprehensive Guide for Students and Educators. The MIT Press.

Ogwueleka, F. N. (2025). Plagiarism Detection in the Age of Artificial Intelligence: Current Technologies and Future Directions. AI and Ethics, Academic Integrity and the Future of Quality Assurance in Higher Education, 10.

ONeill, R., & Russell, A. (2019). Stop! Grammar time: University students' perceptions of the automated feedback program Grammarly. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 35(1).

Perkins, M., Roe, J., Postma, D., McGaughran, J., & Hickerson, D. (2024). Detection of GPT-4 generated text in higher education: Combining academic judgement and software to identify generative AI tool misuse. Journal of Academic Ethics, 22(1), 89-113.

Perkins, M., Roe, J., Postma, D., McGaughran, J., & Hickerson, D. (2023). Game of tones: faculty detection of GPT-4 generated content in university assessments. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.18081.

Rasheed, A. A., Okebukola, P. A., Oladejo, A., Agbanimu, D., Onowugbeda, F., Gbeleyi, O., ... & Adam, U. (in press). AI and Ethics, Academic Integrity and the Future of Quality Assurance in Higher Education.

Safi, R. (2025). Plagiarism in the Age of Generative AI: An Exploratory Experiment. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 56(1), 24.

Singh, J. P., & Kaur, B. P. (2025). Academic Integrity and Ethics in Higher Education: A Case Study on the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Academic Writing and Tackling Plagiarism. In Exploring Digital Metrics in Academic Libraries (pp. 195-224). IGI Global Scientific Publishing.

Siswanto, D. H., Setiawan, A., Wahyuni, N., & Prasetyo, P. W. (2024). Enhancement of Students' Writing Skills Through Training in Scientific Article Writing. Indonesian Journal of Society Development, 3(2), 63-74.

Turnitin. (2023). AI Writing & Pedagogy. https://turnitin.forumbee.com/t/g9hcsxv/ai-detection-and-Grammarly

Walters, W. H. (2023). The effectiveness of software designed to detect AI-generated writing: A comparison of 16 AI text detectors. Open Information Science, 7(1), 20220158.

Appendix A.

ACADEMIC HONESTY POLICY

Adler University seeks to establish a climate of honesty and integrity. Any work submitted by a student must represent original work produced by that student. This could include, but is not limited to, coursework, presentations, and other professional activities. Any source used by a student must be documented through required references and citations, and the extent to which any sources have been used must be expressly stated in the work.

Academic misconduct generally includes cheating, plagiarism, and research misconduct—but academic misconduct is more broadly defined to refer to any action that involves unethical, illicit, unauthorized, fraudulent, or inappropriate behaviors designed to provide an undue advantage or otherwise aid in whole or part with the completion of required work at Adler University. Students who commit academic misconduct, including (but not limited to) cheating, plagiarism or research misconduct, are subject to a failing grade for the assignment and course and, potentially, immediate dismissal from their program and Adler University.

- Cheating includes, but is not limited to, the following examples:

Unauthorized copying, collaboration, or use of notes, books, or other materials on examinations or other academic exercises including:

- Sharing information about an examination with a student who has not taken that examination;

- Obtaining information about the contents of an examination and/or assignment that the student has not taken;

- Unauthorized use of electronic devices;

- Text messaging or other forms of prohibited communication during an examination;

- Having others complete coursework, write papers, or take tests/quizzes for you, thus representing another's work as your own; and/or

- Unauthorized use and/or possession of any academic material, such as tests, research papers, assignments, or similar materials;

- Collaboration on assignments that are designed to be completed on an individual basis, unless otherwise stated by the instructor.

B. Plagiarism, a specific subset of academic dishonesty, is the representation of another person's work, words, thoughts, and/or ideas as one's own. Plagiarism includes, but is not limited to:

- Copying material and/or using ideas from an article, book, unpublished paper, or any material or source found on the Internet without proper documentation of references and citations, or without properly enclosing quoted material in quotation marks. This includes material retrieved from or generated by artificial intelligence tools, including but not limited to ChatGPT.

- Resubmission of work done for one course, assignment, or task for another. This form of plagiarism does not typically involve the submission of the work of others, but instead, consists of representing as new work what has been previously submitted. Adler University further considers resubmission of work done partially or entirely by another, as well as resubmission of substantial or entire portions of one's own work done in a previous course or for a different professor, to be academic dishonesty, unless the student has received prior approval of the faculty, and the new assignment expands upon the original work;

- Minimally rephrasing, paraphrasing, or revising the work of others without proper citation or credit. Plagiarism also includes sentences that follow an original source too closely, often created by simply substituting synonyms for another person's words;

- Substantial utilization of the published or unpublished work of others without permission, citation, or credit—also known as "cut and paste" or "patch writing"—and including works retrieved from or generated by artificial intelligence tools such as but not limited to ChatGPT; and/or

- Purchasing or otherwise acquiring a work in its entirety and submitting it as one's own.

C. Research misconduct involves the misrepresentation of data or material in research, and includes but is not limited to:

- Misrepresentation of how much effort was expended, or the extent of original contribution made to a research project in which multiple contributors took part;

- Withholding data or materials, involving the refusal to make available for inspection the raw data and sources for student research;

- Data manipulation, involving the suppression or changing of study data to facilitate a desired outcome;

- Data fabrication, involving the intentional production of false or invented study or research data and representing such data as genuine; and/or

- Data falsification, involving the intentional alteration of study or research data and representing such data as genuine.

Academic misconduct allegations are referred to the appropriate person or committee on each campus. All occurrences of academic misconduct, whether inadvertent or intentional, are serious and will be evaluated on a case-by-case basis and students may be subject to disciplinary action up to and including dismissal.

Ignorance of this policy or of any restrictions in place in a particular situation regarding the means by which any assignment, examination, or project can be completed is not a defense to an allegation of academic misconduct. It is each student's responsibility to promptly raise any questions or doubts regarding permitted methods or assistance to the appropriate instructor or advisor. Depending on the severity of the academic misconduct at issue, the level of training, and circumstances associated with the misconduct, consequences can range from failure on specific assignments, or required supplemental education, to dismissal from the student's program and/or Adler University.

As approved by the Chicago, Online, and Vancouver campus faculty councils at Adler University January-February 2024.

Competing interests section: No competing interest

Authors' contributions section: All authors contributed to the paper by writing material and/or editing sections of the paper.