Abstract

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, the rapidly growing field of online education experienced an even greater surge, sparking increased interest in the particulars of effective digital pedagogy. Effective approaches include useful facilitator guidance, well-structured course design and productive instructor feedback. In addition, there is evidence to suggest the need for engaging learner exercises that leverage both the efficacy of traditional test-taking as well as self-referential reflection. While these previous studies point to the efficacy of multidimensional models encompassing these components, few have used assorted attitudinal assessments to gauge the progress students make while engaging with this work. Building on that scholarship, this study proposes and evaluates a new Multidimensional Model for Digital Asynchronous Pedagogy (MMDAP) that can be effectively utilized in teaching the social and behavioral sciences. This study blueprints a course design framework for the MMDAP and employs quasi-experimental research via one-group pretest-posttest analysis of attitudinal scales associated with course objectives to measure growth in students who engage in the MMDAP. Of the 256 pre/post attitudinal assessment sets collected, 218 (85%) indicated higher scores on post-assessments over pre-assessments, demonstrating an improvement in course-related attitudes and skill sets after completing said courses utilizing the MMDAP. This study’s findings support the notion that students perform better on measures of interpersonal communication competence, emotional intelligence, resilience, and social consciousness, after engaging in respective communications, psychology, resilience, and sociology courses utilizing the MMDAP framework.

keywords: online learning, social science, behavioral science, digital pedagogy, quasi-experimental research, pretest-posttest, educational interventions

The MMDAP: An Effective Model for Digital Pedagogy in the Social/Behavioral Sciences

In a recent article in U.S. News and World Report titled “How Online Learning is Reshaping Higher Education,” the benefits of online learning discussed included cost-effectiveness, accessibility, flexibility, and teacher and staff support akin to traditional brick-and-mortar institutions (Fitzgerald, 2022). Don Kilburn, the CEO of UMass Online, observed, “I think we are just at the beginning of the digital transformation” (Fitzgerald, 2022, para. 12). One aspect of the digital transformation Kilburn alludes to is instruction.

Instructional decision-making at the individual faculty level, from textbook adoption to course organization and structure, has a tremendous influence on student experience and academic achievement and success. According to a June 2023 survey by McKinsey and Company, U.S. students “value asynchronous classes, online program structure, and up-to-date content the most in their online courses” (Mowreader, 2023, para. 5). In addition to student values, there is sufficient research to suggest that pedagogy is most successful when promoting an active learning approach. Important aspects of active learning that have been identified as integral for effective online learning include self-assessment, reflection, self-directed learning, problem-based learning, learner interaction, and feedback (Cook & Dupras, 2004). Building on these premises, this study examines the appropriation of curated course materials, facilitator guidance, and learner exercises as critical considerations when developing effective online course content.

Curated Materials

As instructional gatekeepers, faculty determine the “day-to-day decisions concerning both the subject matter and the experiences to which students have access” (Thornton, 1991, p. 247). When curating materials for students, it is important to note the usefulness and effectiveness of virtual, open resource texts. Some studies suggest that students prefer physical textbooks over virtual texts (Millar & Schrier, 2015; Yoo & Roh, 2019). Relatedly, a significant mixed methods study of 896 undergraduate biology students found a significant correlation between student frustration with e-texts and the user experience, technical issues with the e-text, and how the e-text fit within the wider curriculum (Novak, McDaniel, Daday, & Soyturk, 2021). Furthermore, as Romig (2017) concluded, “A hard copy of the textbook was seen by our students as a source of comfort and normality” (p. 182).

Still, digital textbooks and open educational resources (OER) are becoming more widely accepted and accessible across disciplines (e.g., math, science, history). In fact, they’ve eclipsed physical book sales (Romig, 2017). The COVID-19 pandemic helped to make alternatives to printed textbook materials essential to the maintenance of education at all levels when physical texts were unavailable due to extenuating circumstances. Despite digital textbooks and OER’s growing importance in online learning, a survey by Seaman and Seaman (2019) found that over 50% of surveyed faculty were unaware of OER. Lee and Lee (2021), building on Hilton’s (2016) important work, note the improved accessibility and functionality of the latest wave of OER and the inherent safeguards they provide against a future educational crisis.

Digital textbooks have made progress in how they are packaged by publishers. Rodríguez-Regueira and Rodríguez-Rodríguez (2022) bring attention to distinguishing between first and second-generation digital textbooks. The first generation are those that are merely the original printed version in a digital format with limited digital accoutrements and the second generation were designed with digital production and the user in mind to maximize the learning experience. Second-generation digital textbooks, created with the user/student in mind, can create immersive and interactive learning experiences that promote increased student engagement with the material (Castro-Rodríguez, Mali & Mesa, 2022; Qin Sun & Abdourazakou, 2018).

Facilitator Guidance

Teacher presence is an aspect of facilitator guidance that resonates with students. Teachers and students perceive teacher presence differently according to the literature (Blaine, 2019; Gomez-Rey et al., 2016; Van der Klej, 2019; Zayac et al., 2021). A qualitative study surveying 1,041 students and 18 teachers by Wang, Stein, and Shen (2021) revealed the theme of Design and Organization as the highestrated by students and the theme of Facilitating Discourse as the highest rated by teachers (though, interestingly, ranked lowest by students).

Related themes of interest are course organization and valuable course content: “An organized course means communicating the course expectations clearly and precisely with students” (Mohandas, Sorgenfrei, Drankoff, Sanchez, Furterer, Cudney, Laux, & Antony, 2022, p. 52).

Feedback is a key attribute of facilitator guidance that students recognize as central to their learning experience (Berg, Shaw, Burrus, & Contento, 2019). The preferred method of feedback in postsecondary education is written (Johannes & Haase, 2022). In an online setting, narrative feedback tends to be more extensive and nuanced, according to Johnson, Stellmack, and Barthel (2019) though that is not always the case where faculty might focus more on “spelling errors and other corrections on writing mechanics” (Knight, Greenberger, & McNaughton, 2021, p. 117). Borup, West, and Thomas (2015) observed that “although feedback timing and delivery are important, the content of the feedback is paramount” (p. 163).

In a qualitative study of 188 graduate students taking online courses, the highest-ranked facilitation strategies were instructors’ timely responses and feedback. Strategies were aimed at “establishing instructor presence, instructor connection, engagement, and learning” (Martin, Wang, & Sadaf, 2018, p. 52). Similarly, in a qualitative phenomenological study examining 15 faculty in STEM-related fields with global teaching and learning experience, one of the major findings was timely feedback and response (Mohandas et al., 2022).

Learner Exercises

What does learning look like across the spectrum of academic disciplines? For decades it has been associated with successful performance on testing tools and measures. Still effective in promoting participation and preparation, regular online quizzing can help to secure desirable academic outcomes (Marcell, 2008). Yet, in the social sciences, for instance, an equally and often more desirable goal is to cultivate a mature understanding of the Self through the development of empathy and reflection. Research has long confirmed the effectiveness of the self-reference effect. Studies show that “participants recalled significantly more self-referentially encoded words than semantically encoded or structurally encoded words ” (Bentley, Greenaway & Haslam, 2017, p. 16). Encouraging students to become reflective empowers them to integrate the material in useful and practical ways and challenge traditional learning models where rote learning and passive, lecture-based teaching are privileged. Reflective learning can be a pathway to “seeing the everyday from a different perspective than the norm and questioning it in the light of the influences that social class, gender and ethnicity have on learning and on our assumptions and preconceptions” (Fullana, Palliscera, Colomer, & Peñac Pérez-Burrield, 2016, p. 1010).

Allowing a space for students to engage with the material through a critical lens is essential in an increasingly diverse and global environment. In social science courses, such as communications, psychology, and sociology, for example, the human context is an important consideration, leveraging reflective learning opportunities. “During reflection, learners' emotional capacities are activated, which may lead to attitudinal changes to achieve constructive learning” (Liu, Yin, Xu, & Zhang, 2021, p. 116). Liu et al. (2021) further argue that “critical reflection leads to superior learning outcomes and has advantages for attentional processes” (p. 115). Reflective learning is not without its challenges, however, as McGarr and O’Gallchóir (2020) explain, as students calibrate responses to prompts to achieve an optimal result, thus undermining the reflective learning process. How reflective exercises are communicated, framed, and assessed are important considerations for online faculty.

Attitudinal Effects in Online Contexts

Asynchronous learning can be challenging for students (Anzari & Pratiwi, 2021; Pulungan, Jaedun, & Retnawati, 2022). Studies have shown that online learning can present difficulties for students ranging from issues with procrastination and effective time management skills to decreased motivation and academic performance (Han, DiGiacomo, & Usher, 2023). How courses are developed and presented to students is an important consideration in an online learning environment (Mehall, 2020).

The way a class is structured can provide natural scaffolding for students to improve “soft skills”, such as emotional intelligence (EI), self-efficacy, and interpersonal skills, for instance (Jeong, González-Gómez, Cañada-Cañada, Gallego-Picó, & Bravo; Tai, 2016). De Leon-Pineda (2022) found that through intentional online course design and specific instructional interventions, increased self-awareness, a sense of belonging, and connection was achievable for students. The author concludes, “educational institutions should have a conscious intention of providing experiences that will allow students to develop their emotional intelligence (p. 395). Some suggested strategies include modeling emotional intelligence, such as modifying assignments and/or granting additional time, can be a powerful mechanism for building rapport and trust with students, particularly in an online classroom (Majeski, Stover, Valais, & Ronch, 2017). “Specifically, we advocate that instructors model emotional intelligence through their own behavior, and through the design, facilitation, and management of learning to help learners develop this skill through observation” (Majeski et al., 2017, p. 136). Iqbal, Asghar, Ashraf, and Xi (2022), confirm the necessity of incorporating emotional intelligence into the framework of an online course, observing, “emotional intelligence…is a key factor in the academic life of students” (p. 1).

In a study looking at the development of “soft skills” for workplace readiness in a Management Information Systems course at a liberal arts college, Cotler and colleagues (2017) concluded that this under-researched area shows considerable promise as direct instruction (i.e., workshops on self-awareness, empathy, etc.) paired with mindfulness techniques improved students’ emotional intelligence. Similarly, in a LinkedIn survey of 38 online adjunct faculty, Hamilton (2017) discovered that interpersonal skills were considered “a top priority” in connection with the promotion of emotional intelligence (p. 2). Hamilton concluded:

there is research to support incorporating more EI into all levels of education including higher education. The curriculum could be designed with emotional intelligence components in mind…the key to improving students’ EI might be to educate the educators to regard EI as a crucial component in the field of education. (p. 3)

In a quantitative study of 865 undergraduate business major/minor students, Lindsey and Rice (2015) found that the more online classes students took (e.g., zero, 1-4, 5+), the higher their emotional intelligence. The authors suggest that one possible explanation is that “online education provides students with additional opportunities not present in the traditional environment. Online courses may offer more chances for the proper development of interpersonal relationships and social skills…” (pp. 132-33). And, by extension, the use of asynchronous tools, such as discussion boards, creates an “opportunity to provide thought-based, provocative responses which might serve to not only enhance interpersonal skills and practice, but also boost the development and maintenance of social relationships…” (p. 133). Thoughtful consideration and planning are necessary for soft skills such as interpersonal communication to flourish, according to Mehall (2020), who argued “quality instructional and social interaction opportunities in online environments need to be deliberately designed into the course” (p. 186). What does a good model for online course design look like? “[I]nteraction opportunities should be designed in a way that allow students to interact with content, faculty, and other students in a manner that is not fake or forced but meaningful and purposeful” (p. 185). When student characteristics and challenges are factored into the design process, it sets students up for success. As one researcher concluded, “Beliefs about self-efficacy also help determine how much effort people invest in an activity, how long they endure when encountering obstacles, and how resilient they will be in the face of adverse situations” (Tai, 2016, p. 119).

Methods

The social and behavioral sciences encompass many disciplines including but not limited to psychology, sociology, communications, and resilience studies. The leading researcher, possessing graduate degrees in the aforementioned three disciplines (sociology, psychology, and communications) was assigned to facilitate courses in each discipline under the role of Assistant Professor of Liberal Arts at an art and design college in the western United States, under the direct tutelage of the Head of Liberal Arts (second researcher).

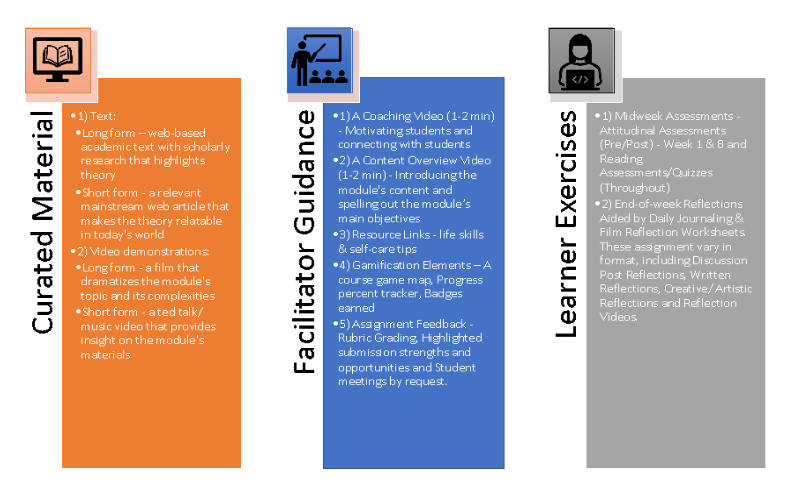

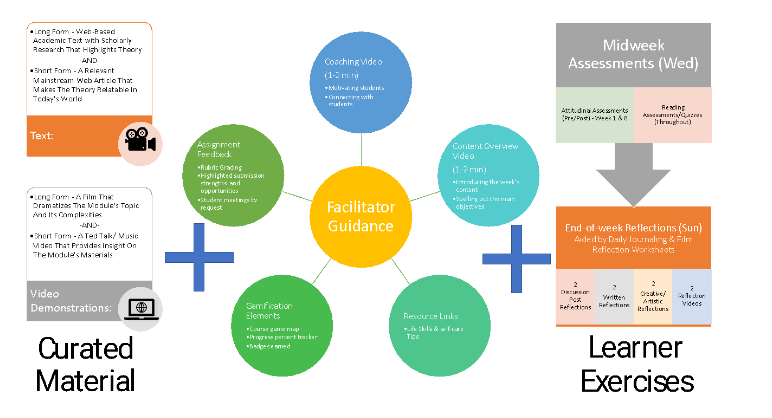

Driven by the literature on effective digital pedagogy, inspired by transformative learning theories and substantiated by the efficacy of blended learning models, the researchers developed a framework for online course design, titled Multidimensional Model for Digital Asynchronous Pedagogy (MMDAP). The model’s primary three pillars include curated materials, facilitator guidance, and learner exercises (included here as Figure 1). Over the course of two academic years (2021-2023), the lead researcher iterated on the model in response to student feedback, academic quality control standards, and instructor trial and error.

Curated Materials are divided into 1) text: long form – web-based academic text with scholarly research that highlights theory and short form – a relevant mainstream web article that makes the theory relatable in today’s world and 2) video demonstrations: long-form – a film that dramatizes the module's topic and its complexities -and- short form – a Ted Talk/ music video that provides insight on the module's materials.

The Facilitator Guidance is divided into five components: 1) A Coaching Video (1-2 min) – Motivating students and connecting with students 2) A Content Overview Video (1-2 min) – Introducing the module's content and spelling out the module’s main objectives 3) Resource Links – life skills & self-care tips 4) Gamification Elements – a course game map, Progress percent tracker, badges earned 5) Assignment Feedback – rubric grading, highlighted submission strengths and opportunities, and student meetings by request.

The third pillar is Learner Exercises which is comprised of two major components: 1) Midweek Assessments - Attitudinal Assessments (Pre/Post) - Week 1 & 8 and Reading Assessments/Quizzes (Throughout) 2) End-of-week Reflections Aided by Daily Journaling & Film Reflection Worksheets. These assignments vary in format, including Discussion Post Reflections, Written Reflections, Creative/ Artistic Reflections, and Reflection Videos. A detailed version of the MMDAP then, encompasses all aspects of each pillar (see Figure 2).

Figure 1

Three Pillars of the Multidimensional Model for Digital Asynchronous Pedagogy (MMDAP)

Figure 2

Detailed MMDAP

The research question posed then was as follows: Is there any evidence to suggest that students engaged in the MMDAP, report attitudinal improvement related to course content?

The researchers hypothesized that given the literature substantiating the benefit of each modality, a Multidimensional approach that combined these modalities would in fact yield beneficial results for students. The research hypothesis was then stated as follows: Students who complete courses utilizing the MMDAP will demonstrate a statistically significant increase in pre to post scores on an associated attitudinal measure, indicating a benefit of course completion.

The leading researcher hence designed and utilized the MMDAP model to facilitate the following courses: “Introduction to Sociology,” “Introduction to Psychology,” “Interpersonal Communication,” and “Culture, Family, and Resilience.” Improved social consciousness, emotional intelligence, interpersonal communication competence, and resilience skills were determined to be the global learning outcomes of those courses respectively.

To evaluate the efficacy of the said model, the leading researcher employed psychometric scales to assist in gauging student growth in relevant content areas throughout students’ participation in the eight weeks of each course. The research proposal was presented to the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). In accordance with U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) requirements for exemptions (2018) from their “Basic HHS Policy for Protection of Human Research Subjects,” the institution determined this study as “Exempt Research,” meeting the following stated HHS criteria. First, it was shown to be “research, conducted in established or commonly accepted educational settings, that specifically involves normal educational practices that are not likely to adversely impact students’ opportunity to learn required educational content or the assessment of educators who provide instruction” (Office for Human Research Protections, 2023, subpart d1). Secondly, it was deemed to be “research that only includes interactions involving educational tests (cognitive, diagnostic, aptitude, achievement), survey procedures, interview procedures, or observation of public behavior” (Office for Human Research Protections, 2023, subpart d2). Thirdly, it also qualified as “research involving benign behavioral interventions in conjunction with the collection of information from an adult subject through verbal or written responses” (Office for Human Research Protections, 2023, subpart d3). In addition, this was all with, “the information obtained is recorded by the investigator in such a manner that the identity of the human subjects cannot readily be ascertained, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects” (Office for Human Research Protections, 2023, subpart d2i). Once the IRB exemption was granted, the study design was refined.

Rationale for Quasi-Experimental Design

This study utilizes a one-group pretest-posttest, quasi-experimental research design to explore the theory that the multidimensional model for digital asynchronous pedagogy (MMDAP) may be positively correlated with improved scores on content-related attitudinal assessments. While control group-assisted experimental designs lead the industry standard for measuring intervention effectiveness, “quasi-experimental designs can offset some ethical and practical issues in true experiments, particularly random selection and assignment” (Barnes, 2019, p. 90). Hence, a quasi-experimental research design was deemed appropriate in this context in the interest of both practicality and ethics. Firstly, the rich data available to the lead researcher by way of students enrolled in the course, presented a practical advantage over the various known challenges associated with securing a control group for each course in question; challenges of time, money, and instructor availability made securing a control group untenable and impractical. More importantly, given the scholarly literature’s support of the pedagogical components infused into the MMDAP (Fullana et al., 2016; Liu, Yin, Xu, & Zhang, 2021; McGarr & O’Gallchóir, 2020) it is reasonable to suggest that withholding effective teaching strategies from students who have entrusted the institution and its faculty to provide the best possible education (simply for the purpose of creating control groups) could be seen as a breach of good faith and deemed unethical. Accordingly, a quasi-experimental design was employed.

As noted in the Encyclopedia of Social Measurement (2005):

Quasi-experiments allow researchers to deal with serious social problems with scientific rigor that, although not equal to that of randomized experiments, controls for many of the most important threats to validity. In many instances, the gain in external validity from adopting a quasi-experimental approach outweighs the loss in internal validity. (Linda, p. 255)

Thus, while this methodology does not provide the degree of internal validity assumed by randomized experiments, its value should not be diminished or dismissed. Campbell and Stanley (1963) draw attention to this sentiment when discussing how scrutiny of design validity can “reduce willingness to undertake quasi-experimental designs, designs in which from the very outset it can be seen that full experimental control is lacking” (p. 34). They go on to insist that:

From the standpoint of the final interpretation of an experiment and the attempt to fit it into the developing science, every experiment is imperfect. What a check list of validity criteria can do is to make an experimenter more aware of the residual imperfections in his design so that on the relevant points he can be aware of competing interpretations of his data. (Campbell & Stanley, 1963)

A reflection on these residual imperfections can be found in the “Limitations” section of this research study. Those imperfections notwithstanding, a quasi-experimental research design was implemented in this study as a informative and revealing manner of examining the correlation between student engagement with the MMDAP and related attitudinal improvements.

Instruments and Procedures

Over the course of two years and 12 academic terms (each consisting of eight weeks), 256 pre/post comparison analyses were conducted of student surveys (across disciplines and scales respectively) collected at the start and end of each term. Respondents consisted of students enrolled in courses taught by the lead researcher throughout the following terms: Spring A 2022 through Summer B 2023. This reflects seven sections of “Interpersonal Communication,” five sections of “Introduction to Sociology,” two sections of “Introduction to Psychology,” and one section of “Culture, Family and Resilience.” Each unique combination of student and course symbolized a unique assessment opportunity. One student may have taken more than one of the courses in question and would thus have been surveyed at different times about different attitudes in different content areas. Each course survey is then deemed an assessment possibility. Represented in this study are 86% of the total 299 assessment possibilities. While some students took more than one course and are therefore included in the study multiple times, their assessment represent 256 unique student-course combinations. Over the two years of coursework, 43 (14%) assessment opportunities were excluded from the study, due to missing pre or post-assessment scores. This included students who simply did not complete one or both assessments as well as students who joined a course late or withdrew from a course early. Attitudinal growth was measured using several content-specific scales across courses (see Table 1). For the assessment of emotional intelligence, the researcher utilized the scientifically valid and reliable measure “The Schutte Self Report Emotional Intelligence Test (SSEIT)” – a thirty-three item self-inventory designed to measure emotional intelligence across four subscales: emotion perception, utilizing emotions, managing self-relevant emotions and managing others’ emotions (Schutte & Malouff, 1998).

Table 1

Courses and Respective Attitudinal Assessments

| Course | Outcome | Assessment | Skills | Citation |

| Introduction to Psychology | Emotional intelligence | The Schutte Self Report Emotional Intelligence Test (SSEIT) | emotion perception, utilizing emotions, managing selfrelevant emotions and managing others’ emotions | Schutte & Malouff, 1998 |

| Resilience, Culture & The Family | Resilience Skills | The CD-RISC10 | resilience or how well one is equipped to bounce back after stressful events, tragedy, or trauma | Connor & Davidson, 2003 |

| Interpersonal Communication | Improved Interpersonal Communication Competence | Interpersonal Communication Competence Self-Assessment | interpersonal communication competence as knowledge skill, and motivation | Spitzberg & Cupach, 1984 |

| Introduction to Sociology | Increased social consciousness | The Social Consciousness Self-Assessment Questionnaire | empathy, compassion, community activism and an understanding of a relationship between society and the self | Nieves, 2022 |

To assess resilience skills, “The CD-RISC-10” (a ten-item adaptation of “The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale”) was employed as a validated inventory (Connor & Davidson, 2003) that measures resilience or how well one is equipped to bounce back after stressful events, tragedy, or trauma.

For the assessment of interpersonal communication competence, students were given the eighteen-item “Interpersonal Communication Competence Self-Assessment” (Spitzberg & Cupach, 1984), built on the component model (Spitzberg & Cupach, 1984) which explores the three basic components of interpersonal communication competence as knowledge, skill, and motivation.

Given the lack of validated scales to measure social consciousness, the “Interpersonal Communication Competence Self-Assessment” (Spitzberg & Cupach, 1984) was adapted to a corresponding eighteen-item self-report measure inquiring about respondent empathy, compassion, community activism, and an understanding of a relationship between society and the self (Nieves, 2022). The “Interpersonal Communication Competence Self-Assessment” already explored various relevant concepts including self-awareness and empathy, rendering a strong choice for adaptation. All assessment responses operated on a Likert scale with attached numerical values and total sums signifying “scores” in each measure of either social consciousness, emotional intelligence, resilience skills, or interpersonal communication competence. Scores at the beginning of each term were compared with scores at the end of each term (on the same measure) to evaluate change in respondent attitude. Again, of the 299 unique assessment opportunities, 256 (86%) completed sets of pre and post-assessments were collected from students across the four courses.

Results

Two hundred, and fifty-six sets of (pre and post) assessments were collected from students in a span of two years across 12 sections of courses, representing four content areas, taught by the lead researcher. Fourteen sets were collected in 2021, 148 sets were collected in 2022 and 94 were collected in 2023 (see Table 2).

Table 2

Number of Student Assessments Per Year

| Year | Number of Students Assessments |

| 2021 | 14 |

| 2022 | 148 |

| 2023 | 94 |

| Total | 256 |

The data set included various assessment types such as The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale-10 (n=16), The Schutte Self Report Emotional Intelligence Test (n=27), The Interpersonal Communication Competence Self-Assessment (n=94), and The Social Consciousness Self-Assessment Questionnaire (n=119, see Table 3).

Table 3

Number and Types of Student Assessments Per Course

| Course | Assessment Scale | Number of Students |

| Interpersonal Communication | The Interpersonal Communication Competence Self-Assessment | 94 |

| Introduction to Sociology | The Social Consciousness Self-Assessment Questionnaire | 119 |

| Introduction to Psychology | The Schutte Self Report Emotional Intelligence Test | 27 |

| Culture, Family & Resilience | The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale-10 | 16 |

| Total | 256 |

Of the 256 sets collected, 218 (85%), showed higher scores on post-assessments than scored on pre-assessments, suggesting an increase and/or improvement in the attribute assessed (see Table 4).

Table 4

Pre/Post Score Comparisons

Pre/Post Score Comparisons

| Pre/Post Score Comparison | Number of Student Assessments | Percent of Student Assessments |

| Improved | 218 | 85% |

| Remained | 8 | 3% |

| Worsened | 30 | 12% |

| Total | 256 | 100% |

The majority of data sets, therefore, presented a notable increase in scores from pre to post-assessment, indicating growth in each measured attribute. Thirty sets (12%) reported lower scores on post-assessments than on pre-assessments. When asked about the lower post score, many of these students pointed to an increased understanding of the assessment questions after course completion, informing more accurate responses on the post-test. Eight (3%) assessment pre/post sets reported post-scores consistent with their respective pre-scores.

Interpersonal communication competence (M=7.43) and social consciousness (M=6.72) both reportedly increased an average of seven points, with resilience (M=5.09) and emotional intelligence (M=4.52) both increasing an average of about five points (see Table 5).

Table 5

Average Difference from Pre to Post Score by Course

| Course | Average of Difference from Pre to Post |

| Interpersonal Communication | 7.425531915 |

| Introduction to Sociology | 6.722689076 |

| Introduction to Psychology | 4.518518519 |

| Culture, Family & Resilience | 5.09375 |

| Total | 6.646484375 |

The total average difference for all 256 sets collectively, was 6.46 points, suggesting an overall average improvement in the desired attribute associated with participation in the related course.

A paired t-test was performed to determine if participation in said related courses, utilizing the Multidimensional Model of Digital Asynchronous Pedagogy (MMDAP) yielded a statistically significant increase in self-assessment scores in the areas of social consciousness, interpersonal communication competence, emotional intelligence, and resilience. Since the alpha value was set to 0.05, a p-value of less than 0.05, would indicate a statistically significant difference between the assessment means before and after engaging in the course. As the p-value was determined to be 3.05 x 10-36, which is lower than the significance level alpha=0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected. This means that for this set of scores, there is a difference between the pre-assessment score mean of 72.94 and the post-assessment score mean of 79.59 which is not likely due to chance (see Table 6).

Table 6

t-Test Analysis

| t-Test: Paired Two Sample for Means | Variable 1 Variable 2 |

| Mean | 79.58789063 72.94140625 |

| Variance | 218.6245979 261.5534161 |

| Observations | 256 256 |

| Hypothesized Mean Difference | 0 |

| df | 255 |

| t Stat | 14.81342038 |

| P(T<=t) one-tail | 1.52674E-36 |

| t Critical one-tail | 1.650851092 |

| P(T<=t) two-tail | 3.05348E-36 |

| t Critical two-tail | 1.96931057 |

Statistical analyses of the data further demonstrate that the t-statistic value (14.81) is greater than the t-critical (1.97), affirming the rejection of the null hypothesis. Because the critical value approach involves determining "likely" or "unlikely" by determining whether or not the observed test statistic is more extreme than would be expected if the null hypothesis were true, these findings further suggest that it is unlikely that the increase in post assessment scores is due to chance.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to propose and evaluate a Multidimensional model for digital asynchronous pedagogy (MMDAP) that can be effectively utilized in teaching the social and behavioral sciences. There exists ample research to support the MMDAP’s components, beginning with the effectiveness of digital textbooks and open educational resources (Romig, 2017; Castro-Rodríguez et al., 2022; Qin Sun & Abdourazakou, 2018) paired with useful guidance from a course facilitator (Blaine, 2019; Gomez-Rey et al., 2016; Van der Klej, 2019; Zayac et al., 2021) in a well-structured course (Wang et al., 2021; Mohandas et al., 2022) enhanced by productive feedback from the course instructor (Johannes & Haase, 2022; Johnson, Stellmack, & Barthel, 2019; Knight, Greenberger, & McNaughton, 2021). In addition, the MMDAP engages students in effectual learner exercises that leverage both the efficacy of traditional test-taking (Marcell, 2008) as well as self-referential reflections via myriad forms of expression, including written, video and artistic reflections (Bentley et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2021; McGarr & O’Gallchóir, 2020).

Still, while previous studies have pointed to the efficacy of multidimensional models encompassing these components, few have used varied attitudinal assessments to gauge the progress students make while engaging with this work. When compared with their performance before engagement with the MMDAP coursework, this study’s findings support the notion that students perform better on measures of interpersonal communication competence, emotional intelligence, resilience and social consciousness, after engaging in respective communications, psychology, resilience, and sociology courses utilizing the MMDAP.

It was hypothesized that combining evidence-based digital teaching modalities would yield positive results in improving the attitudes and skill sets of students taking asynchronous digital courses in the social and behavioral sciences. As hypothesized, the more than 250 attitudinal assessments of students who participated in social and behavioral science courses taught by the lead researcher between 2021 and 2023, indicated higher scores on their post-assessments than on their pre-assessments, demonstrating an improvement in course-related attitudes and skill sets after completing said courses utilizing the MMDAP.

The difference in average increase across courses (4.5 emotional intelligence, 5.1 resilience, 6.7 social consciousness, 7.5 interpersonal communication competence) suggests only a minor variation in the efficacy of this model across content areas. On average, student scores improved by roughly six and a half points, indicating a statistically significant benefit to the student.

Limitations

The data from this study stems from a single institution, using eight-week courses facilitated by only one instructor – the lead researcher. This limits the generalizability of the study’s findings and renders it difficult to conclude, beyond doubt, that the findings are unique to the MMDAP approach. A quasi-experimental research design was used. No control group was utilized to compare and contrast the results of pre and post-assessments for students taking MMDAP courses, to those of students taking the coursework without the use of the MMDAP. Therefore, it remains unclear to what degree the improvement demonstrated by students can be exclusively attributed to the MMDAP approach. As Campbell and Stanley (1963) observed, there are many challenges associated with quasi-experimental research of the one-group pretest-posttest design, in the area of uncontrolled rival hypotheses. Those most relevant to the present study include history, maturation, and testing. It is always plausible that between pretesting and post-testing of study participants, many other change-producing events may have occurred that affected the measured change, in addition to the educational intervention—history. It is also possible that the measured change could have been impacted by the biological and psychological processes which systematically vary with the passage of time, independent of the educational intervention—maturation. Moreover, the measured change could have been impacted by the notion that individuals taking a test for the second time usually do better than those taking the test for the first time—testing (Campbell and Stanley, 1963). Still, what is clear is that social and behavioral courses taught utilizing the MMDAP yielded statistically significant improvement in related attitudinal assessments among its students.

Another limitation involves the scales used to measure attitudinal and skill set improvement. For one, the use of the social consciousness self-assessment questionnaire, which while adapted from a valid and reliable scale, has not itself been validated as a psychometric measure of scientific reliability. In addition, the decision was made by the lead researcher to focus on improved emotional intelligence as the goal of taking a course in “Introduction to Psychology,” as well as setting increased interpersonal communication competence as the objective of engaging in a course in interpersonal communication. Likewise, increased resilience and increased social consciousness were determined to be the aims of engagement in the courses “Culture, Family & Resilience,” and “Introduction to Sociology” respectively. It may be argued that students and teachers of these courses may have different aims and, thus, ways to measure the successful integration of the course content.

Further investigation into the efficacy of the MMDAP would include the use of the model across a variation of courses, instructors, and institutions in addition to utilizing other relevant measures of content-related attitudinal and skill set improvement.

Despite its limitations, this study serves to advance our understanding of effective digital pedagogy and proposes a structured, replicable model for institutions of higher education to adapt as the academic world continues to navigate a shift toward increased interest in online education.

Conclusions

The COVID pandemic and subsequent global quarantine, brought with it a spike in digital education requests and availability. Despite the world’s continued recovery and readjustment, the trend toward increased online learning persists. This research study was intended to contribute to the current conversation around digital pedagogy. It is a particularly relevant study, at a time when many universities grapple with the transitional challenges of offering increased online education courses. Many faculty members have little time for pedagogical experimentation and increasing demands for student-focused learning models that transfer to real-world student benefit. Consequently, it is imperative that viable options be made readily available. Now more than ever, there is a growing need for effective models in asynchronous digital pedagogy. The Multidimensional Model of Digital Asynchronous Pedagogy (MMDAP) proposed in this study, offers faculty members precisely such a recipe for student success.

Under the combined umbrellas of well-curated content, facilitator guidance, and learner exercises, the MMDAP lays out specific components that teaching staff can blend to effectively engage students in asynchronous online courses. This study offers evidence to suggest that students engaged in social and behavioral science courses utilizing the MMDAP, demonstrate significant attitudinal and skill set improvement in related content areas.

References

Anzari, P. P. & Pratiwi, S. S. (2021). What’s missing? How interpersonal communication changes during online learning. Asian Journal of University Education, 17(4), 148-157. https://doi.org/10.24191/ajue....

Barnes, B. R. (2019). Quasi-experimental designs in applied behavioural health research. In S. Laher, A. Fynn, & S. Kramer (Eds.), Transforming Research Methods in the Social Sciences: Case Studies from South Africa (pp. 84–96). Wits University Press. https://doi.org/10.18772/22019...

Bentley, S. V., Greenaway, K. H., & Haslam, S. A. (2017). An online paradigm for exploring the self-reference effect. PLOS ONE, 12(5). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176611

Berg, C. W., Shaw, M. E., Contento, A. L., & Burrus, S. W. M. (Jan. 2019). A qualitative study of student expectations of online faculty engagement. In K. Walters (Ed.), Fostering multiple levels of engagement in higher education environments. (pp. 220-236). Hershey, PA: IGI Global. DOI: 10.4018/978-1-5225-7470-5.ch010

Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research. Houghton Mifflin Company. Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor‐Davidson resilience scale (CD‐RISC). Depression and anxiety, 18(2), 76-82.

Cook, D. A., & Dupras, D. M. (2004). A practical guide to developing effective web-based learning. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 19(6), 698–707. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525...

Cotler, J. L., DiTursi, D., Goldstein, I., Yates, J., & DelBelso, D. (2017). A mindful approach to teaching emotional intelligence to undergraduate students online and in person. Information Systems Education Journal, 15(1), 12-25. https://isedj.org/2017-15/n1/I...

De Leon-Pineda, J. L. (2022). How do you feel today? Nurturing emotional awareness among students in online learning, Reflective Practice, 23(3), 394-408. DOI: 10.1080/14623943.2022.2040010

Fitzgerald, M. (2022, Feb. 15). How online learning is reshaping higher education. U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved from https://www.usnews.com/news/ed...

Fullana, J., Pallisera, M., Colomer, J., Fernández Peñac, R., & Pérez-Burrield, M. (2016). Reflective learning in higher education: a qualitative study on students’ perceptions. Studies in Higher Education, 41(6), 1008-1022. DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2014.950563

Hamiton, D. (2017). Examining perceptions of online faculty regarding the value of emotional intelligence in online classrooms, Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 20(1), 1-14. https://ojdla.com/archive/spri...

Han, J., DiGiacomo, D. K., & Usher E. L. (2023). College students’ self-regulation in asynchronous online courses during COVID-19. Studies in Higher Education, 48(9), 1440-1454. DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2023.2201608

Iqbal, J., Asghar, M. Z., Ashraf, M. A., & Yi, X. (2022). The impacts of emotional intelligence on students’ study habits in blended learning environments: The mediating role of cognitive engagement during COVID-19, Behavioral Sciences, 12(14), https://doi.org/10.3390/bs1201...

Jeong, J. S., González-Gómez, D., Cañada-Cañada, F., Gallego-Picó, A., & Bravo, J. C. (2019). Effects of active learning methodologies on the students’ emotions, self-efficacy beliefs and learning outcomes in a science distance learning course. Journal of Technology and Science Education, 9(2), 217-227. DOI: 10.3926/jotse.530

Lee, D. & Lee, E. (2021). International perspectives on using OER for online learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69, 383-387. DOI: 10.1007/s11423-020-09871-5

Linda, H. (2005). Quasi-experiment. (K. Kempf-Leonard, Ed.).Encyclopedia of Social Measurement, 255–261. DOI: 1016/b0-12-369398-5/00002-5

Lindsey, N. S. & Rice, M. L. (2015). Interpersonal skills and education in the traditional and online classroom environments. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 13(3), 126-136. https://www.ncolr.org/jiol/iss...

Liu, Z., Yu, H., Cui, W., Xu, B., & Zhang, M. (2022). How to reflect more effectively in online video learning: Balancing processes and outcomes. British Educational Journal of Technology, 53, 114-129. DOI: 10.1111/bjet.13155

Ma, H. (2021). Empowering digital learning with open textbooks. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69, 393-396. DOI: 10.1007/s11423-020-09916-9

Majeski, R. A., Stover, M., Valais, T., & Ronch, J. (2017), Fostering emotional intelligence in online higher education courses. Adult Learning, 28(4), 135-143.

Marcell, M. (2008). Effectiveness of regular online quizzing in increasing class participation and preparation. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 2(1), DOI: 10.20429/ijsotl.2008.020107

McGarr, O. & O’Gallchóir, C. (2020). The futile quest for honesty in reflective writing: recognizing self-criticism as a form of self-enhancement. Teaching in Higher Education, 25(7), 902-908. DOI: 10.1080/13562517.2020.1712354

Mehall, S. (2020). Purposeful interpersonal interaction in online learning: What is it and how is it measured? Online Learning, 24(1), 182-204. DOI: 10.24059/olj.v24i1.2002

Millar M. & Schrier, S. (2015). Digital or printed textbooks: Which do students prefer and why?. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 15(2), 166-185. DOI: 10.1080/15313220.2015.1026474

Mowreader, A. (2023, June). Supporting online student engagement with course design. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com...

Nieves, D. (2022, March). Toward A new measure of social consciousness [Poster presentation]. American Association of Behavioral and Social Sciences (AABSS) Digital Conference 2022, Virtual. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/...

Novak, E., McDaniel, K., Daday, J., & Soyturk, I. (2022). Frustration in technology-rich learning environments: A scale for assessing student frustration with e-textbooks. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53, 408-431. DOI: 10.1111/bjet.13172

Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP). (2023, May 31). Exemptions (2018 requirements). HHS.gov. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regul...

Pulungan, D. A., Jaedun, A., & Retnawati, H. (2022). Mathematical resilience: How students survived in learning mathematics online during the Covid-19 pandemic. Qualitative Research in Education, 11(2), 151-179. DOI: 10.17583/qre.9805

Qin Sun, T. J. N. & Abdourazakou, Y. (2018). Perceived value of interactive digital textbook and adaptive learning: Implications on student learning effectiveness. Journal of Education for Business, 93(7), 323-331. DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2018.1493422

Rodríguez-Regueira, N. & Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J. (2022). Analysis of digital textbooks. Educational Media International, 59(2), 172-187, DOI: 10.1080/09523987.2022.2101207

Romig, K. (2017). Should geography educators adopt electronic textbooks? Journal of Geography, 116(4), 180-184. DOI: 10.1080/00221341.2016.1215489

Seaman, J. E., & Seaman, J. (2019). Inflection point: Educational resources in U.S. higher education. Retrieved from https://www.onlinelearningsurv...

2019inflectionpoint.pdf

Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M., Hall, L. E., Haggerty, D. J., Cooper, J. T., Golden, C. J., & Dornheim, L. (1998). Development and validation of a measure of emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 25(2), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-...(98)00001-4 Spitzberg, B. H., & Cupach, W. R. (1984). Interpersonal communication competence (Vol. 4). SAGE Publications, Incorporated.

Tai, H. C. (2016). Effects of collaborative online learning on EFL learners’ writing performance and self-efficacy. English Language Teaching, 9(5), 119-133.DOI:10.5539/let.v9n5p119

Yoo, D. K. & Roh, J. J. (2019). Adoption of e-books: A digital textbook perspective. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 59(2), 136-145. DOI: 10.1080/08874417.2017.1318688