Abstract

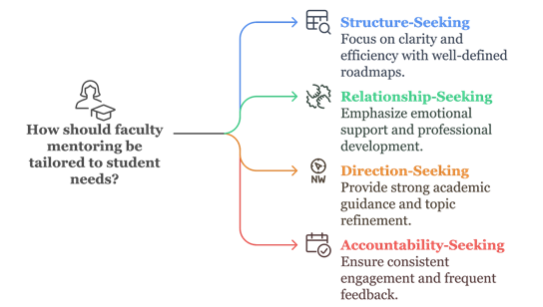

Online doctoral students face unique challenges in completing their dissertations, with faculty mentoring playing a crucial role in their success or attrition. This study explores online doctoral students’ viewpoints of faculty dissertation mentoring, identifying distinct mentoring viewpoints. Using Q methodology, we examine how students prioritize different aspects of mentoring, such as structured guidance, emotional support, academic direction, and accountability. Q method is a research approach that explores subjective viewpoints by having participants rank and sort statements to reveal patterns in their perspectives. Findings reveal four distinct mentoring preference types: Structure-Seeking Students, who require clarity and efficiency; Relationship-Seeking Students, who prioritize emotional support and research connections; Direction-Seeking Students, who need strong academic guidance; and Accountability-Seeking Students, who benefit from consistent engagement and feedback. Grounded in Self-Determination Theory (SDT), this study highlights the distinct viewpoints of online doctoral students regarding faculty dissertation mentoring and provides practical recommendations for faculty and administrators to enhance mentoring strategies. Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is a psychological framework that emphasizes how autonomy, competence, and relatedness drive human motivation and well-being.

Keywords: Q Method, Online Doctoral Students, Dissertation Mentoring, Self-Determination Theory

Online Doctoral Students’ Viewpoints on Faculty Dissertation Mentoring

Faculty members are essential to the success of hybrid Ph.D. programs and should carefully examine how their mentoring strategies help students achieve their goals (McNeill et al., 2024). Doctoral students in online programs face unique challenges in completing their dissertations, with faculty mentoring often determining their success or attrition. Unlike traditional, in-person doctoral programs where students are on-campus and benefit from frequent, informal interactions with faculty, online students rely more heavily on structured mentoring relationships to navigate the dissertation process. However, even traditional on-campus doctoral students have historically been unclear about how the process works (Golde & Dore, 2001). Bartlett et al. (2018) emphasized that mentoring is a crucial component in redesigning doctoral programs for working professionals that included early assignment of chairs. Mentoring is not a one-size-fits-all experience; faculty may struggle to provide support that aligns with individual student needs. One of the key challenges in online doctoral education is ensuring that faculty mentoring effectively fosters student motivation, engagement, and persistence in a virtual environment where interactions are often asynchronous and less personalized.

The problem this study addresses is that while mentoring is widely recognized as essential to dissertation completion, little is known about the specific dissertation mentoring viewpoints of online doctoral students. The purpose of this study is to identify and examine different mentoring viewpoints among online doctoral students, providing insights into how faculty can tailor their mentoring approaches to better support students throughout the dissertation process. Given the unique challenges of online doctoral education, students may have varying expectations and needs regarding faculty mentoring, ranging from structured guidance to emotional support and accountability. This study explored the research question: What are online doctoral students' viewpoints of faculty dissertation mentoring?

Literature

Shulman (2010) outlines four key academic practices of the Ph.D. that include scholarship (problem framing, research, and communication), effective teaching (utilizing the newest technology and assessment), supervision and mentoring (guidance, coaching and support), and public service (civic engagement and outreach) (p. B7). Collins, Brown, and Newman (2018) developed a framework of cognitive apprenticeship that can be applied to a doctoral program in which the expert (mentor) helps the novice (doctoral students) develop expertise to transition from knowledge consumer to independent scholar (Swanson et al., 2015). One key challenge in dissertation advising is the misalignment between faculty and student expectations, which can impact student success, satisfaction, and completion rates. (Golde, 2005). In some cases, faculty can be seen as those that serve as gatekeepers to the profession setting high standards for scholarship (Bartlett et al., 2024; Oltman et al., 2019). However, they also play another role of that of mentor, to provide students guidance on professional issues, academics, and research including the dissertation (Burrington et al., 2022). Moses, I. (1985) developed an instrument that advisors and students can use to discuss the advising relationship which was further adapted by Kiley & Cadman (1997), then further adapted by Golde (2010). The purpose of this assessment was not to change advisor or advisee styles but suggested to make those involved aware of their styles to provide upfront expectations and points to discuss throughout the advising process. Siesfeld's (2024) study highlights that strong engagement and structured faculty support is key to student persistence in online doctoral programs, with dissertation chairs and mentors playing a crucial role by providing timely feedback, fostering supportive relationships, and offering structured guidance to enhance retention and success.

Theoretical Framework

Self-Determination Theory (SDT), developed by Deci and Ryan (1985), is a psychological framework that explores human motivation, emphasizing the importance of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. This study applies SDT alongside the integration of signature pedagogy to foster the successful completion of a dissertation. Signature pedagogy refers to a discipline’s distinctive approach to teaching and learning (Shulman, 2005). By strategically applying these concepts to foster autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the profession, mentoring serves as a critical mechanism for developing scholars.

Integrating these two theories posits that individuals are most motivated and engaged when three fundamental psychological needs are met: autonomy (a sense of control over one’s actions and decisions), competence (feeling capable and effective in one’s endeavors), and relatedness (a sense of connection and belonging with others). Mentoring can provide the instructional support necessary for the development of scholars by addressing these psychological needs. SDT has been widely applied in educational settings to understand how learning environments and support systems impact motivation and performance. It is a strong fit for this study because doctoral students’ experiences with dissertation mentoring are deeply tied to their motivation, persistence, and self-efficacy. Faculty mentoring plays a critical role in either fulfilling or hindering these psychological needs, ultimately influencing student engagement, dissertation progress, and completion rates.

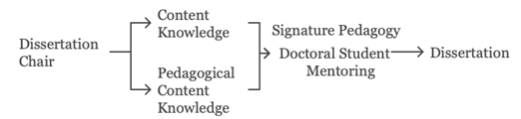

By applying SDT, this study examines how different mentoring styles align with students’ motivational needs, providing insight into the types of faculty support that sustain doctoral students in an online learning environment. The figure below illustrates how the dissertation chair provides content knowledge (an understanding of the subject matter) using a pedagogical strategy, pedagogical content knowledge (Shulman, 1986), to make the content understandable. This is done through mentoring to support the independent completion of a dissertation. However, the mentoring process and the specific mentoring expectations of students may be viewed in a variety of formats, requiring flexibility and adaptation to best support individual doctoral candidates.

Figure 1

Faculty Dissertation Mentoring as a Signature Pedagogy

Q Method Approach

Q method is a mixed-methods research approach that combines quantitative factor analysis with qualitative interpretation to explore subjective viewpoints on a given topic (Ramlo, 2024; Ramlo & Newman, 2011). Unlike traditional surveys that measure frequency-based responses, Q methodology uncovers patterns in perspectives by having participants rank and sort statements based on personal significance (Brown, 1980; McKeown & Thomas, 2013; Stephenson, 1953). The statistical factor analysis then groups participants who share similar perspectives, revealing distinct viewpoints within a population. This approach was particularly well-suited for this study because doctoral students have diverse and deeply personal expectations of faculty mentoring, shaped by their academic backgrounds, work styles, and motivations. By allowing participants to prioritize what aspects of mentoring matter most to them, Q methodology provided a structured yet flexible way to identify and categorize these perspectives.

Participants (P-set)

In Q methodology, the P-set represents the group of participants who sort statements according to their personal perspectives, enabling researchers to identify patterns in viewpoints (Bartlett & Bartlett, 2023). It is appropriate to have a highly defined P-set in a specific content and (Brown, 1980) and in this study's the P-set comprises online doctoral students from two PhD programs at a Research 1 university. According to McKeown and Thomas (2013) a p-set from 15-40 would allow a meaning factor extraction. For this study, students (N=20) were categorized into two groups: Early Doctoral Students (n=9), who are in the initial stages of their coursework, and Late Doctoral Students (n=11), who have completed their coursework. This classification facilitates an analysis of how students’ expectations and experiences with faculty dissertation mentoring evolve throughout their doctoral studies. By comparing these groups, the study seeks to reveal differences in mentoring needs, support systems, and the overall influence of faculty guidance at various stages of the doctoral journey.

Concourse to Q-sample

The process of moving from the concourse to the Q sample in this study involved refining a broad set of statements into a structured set for analysis. The concourse consisted of 105 statements that were sourced from a variety of materials, including journal articles, books, conversations with doctoral students and faculty, interviews, social media posts, discussion forums, and personal reflections on faculty dissertation mentoring experiences in online doctoral programs. These diverse sources provided a comprehensive foundation for capturing a wide range of perspectives on faculty dissertation mentoring. Using Fisher’s Design of Experiments balanced block design (Ramlo, 2024; Ramlo, 2025), the statements were systematically reduced to a structured Q sample of 25 statements, categorized equally into five themes: Research Guidance and Expertise, Feedback and Quality Assurance, Emotional Support and Motivation, Communication and Accessibility, and Advocacy and Mentorship. This structured Q sample ensures a balanced representation of perspectives, allowing for a deeper exploration of doctoral students' expectations and experiences of faculty dissertation mentoring. By organizing the statements into these key themes, the study provides a framework for understanding how students prioritize different aspects of faculty support throughout their doctoral journey.

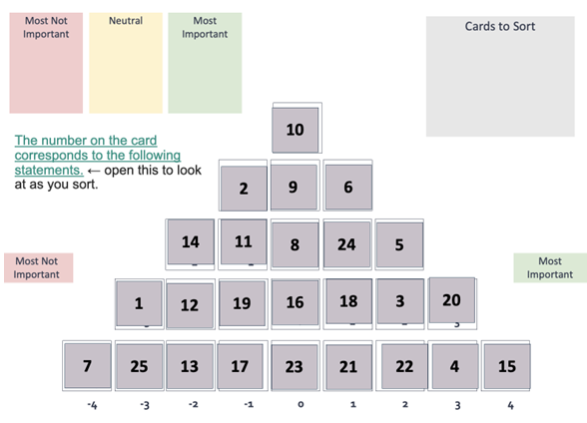

Data Collection through Q-sort

The data collection process employed Q methodology, where online doctoral students engaged in a structured Q-sort activity using a PowerPoint-based task. Participants received a PowerPoint file containing 25 statements derived from a structured Q sample, which were selected based on key themes related to faculty mentoring in online doctoral programs. Following a condition of instruction, students were asked to drag and drop the statement cards onto a provided grid, seen below in Figure 1, in relation to what they perceived as most important and least important in the role of faculty mentoring (dissertation chair) as a doctoral student. They were instructed to drag from the stack of cards and place them on the grid, positioning the most important mentoring behaviors on the right (+4) and the least important on the left (-4).

Figure 2

Snapshot of PowerPoint for Q Sorting

Participants first categorized the statements into three preliminary groups: Most Important, Neutral, and Least Important. They then arranged the statements onto a forced-choice distribution grid, ranking them based on their perceived importance. Each statement was assigned a random number for reporting purposes, and every slot on the grid required placement of one statement. After completing the sorting task, participants answered a series of open-ended survey questions to provide further insights into their choices. They were asked to justify their highest-ranked (+4) and lowest-ranked (-4) statements, explaining why they placed them in those positions. Additionally, they had the opportunity to suggest any missing statements they believed should have been included and indicate where they would have placed them on the grid.

To capture demographic context, participants provided details such as gender, enrollment status (full-time or part-time), doctoral major, number of credit hours completed, estimated dissertation completion time, and employment status while studying. Once the sorting and survey responses were completed, participants submitted their finalized PowerPoint files via email for analysis. This structured approach allowed for a systematic examination of doctoral students’ expectations and experiences of faculty mentoring, ensuring that their subjective viewpoints were captured and analyzed within the Q methodology framework.

Data Analysis

The data collected from the Q-sort activity was analyzed using KADE (Ken-Q Analysis Desktop Edition), a software designed for Q methodology analysis (Banasick, 2023). To extract factors, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied, followed by Varimax rotation to enhance interpretability. The 25 statements sorted by 20 participants (online doctoral students who have completed coursework, n=11 and online doctoral students who have just begun coursework, n=9) were first uploaded into KADE, where eight principal components were initially extracted. Based on eigenvalues and interpretability, four factors were selected for rotation. Varimax rotation was then applied to maximize variance among the factors, ensuring each was defined by a distinct set of participants.

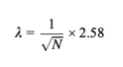

The final rotated factor solution yielded four factors, each representing a unique perspective on faculty mentoring in online doctoral programs. The explained variance for these factors was 18% for Factor 1, 16% for Factor 2, 14% for Factor 3, and 10% for Factor 4. Each Q-sort was correlated with these factors and defining sorts (those significantly loading onto a factor) were identified. A significant factor loading was determined by:

Where N represents the total number of statements (25 in this study), and 2.58 is the critical value for a 99% confidence level; thus, any factor loading above 0.516 is considered statistically significant. Participants 3 and 18 did not meet the 0.516 threshold as seen in Table 1 below. The flagged Q-sorts (above .516) were used to construct factor interpretations, based on participants' highest and lowest-ranked statements within each factor.

Table 1

Factor Loading Table for Four Factor Solution with Varimax Rotation

| Q Sort | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 |

| 12 | .7969 | -.2262 | .1448 | .3330 |

| 19 | .6615 | -.0148 | -.0548 | -.1323 |

| 1 | .6379 | .0357 | .2279 | .1349 |

| 15 | .6374 | .1590 | .0284 | .2275 |

| 8 | .6101 | .1345 | .3189 | .0461 |

| 20 | .5934 | .0632 | -.0540 | -.3370 |

| 3 | .4722 | .1387 | -.0641 | .0287 |

| 11 | -.3431 | .7495 | .2465 | -.0239 |

| 17 | .2030 | .7173 | -.1958 | -.3606 |

| 7 | .3799 | .6807 | -.1234 | .1573 |

| 6 | .0890 | .6380 | .4461 | .1173 |

| 2 | .3387 | .5856 | .1672 | .0430 |

| 4 | -.0938 | .5724 | .0188 | .2770 |

| 18 | .0771 | .4349 | -.1025 | -.0604 |

| 9 | .0632 | -.0016 | .8857 | -.1280 |

| 16 | .1573 | -.3781 | .7654 | -.0972 |

| 10 | .1535 | .0983 | .7161 | .2405 |

| 5 | -.2032 | .3618 | .5591 | -.2257 |

| 13 | -.0465 | .0454 | -.1006 | .8448 |

| 14 | .3844 | .0552 | .0036 | .6973 |

The analysis also identified distinguishing statements (p < 0.01, p < 0.05) that significantly differentiated each factor. Factor 1 emphasized the importance of clear communication and structured direction throughout the dissertation process. Factor 2 prioritized mentorship beyond the dissertation, highlighting the value of career development and networking opportunities. Factor 3 focused on the dissertation chair’s expertise and methodological guidance, while Factor 4 underscored the need for timely feedback and motivation from faculty mentors. Additionally, as seen in Table 2, the factors were correlated at low to moderate levels, suggesting distinct but related perspectives on faculty mentoring.

Table 2

Factor Correlations Between the 4 Unique Viewpoints

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | |

| Factor 1 | 1 | |||

| Factor 2 | .1019 | 1 | ||

| Factor 3 | .2103 | .0845 | 1 | |

| Factor 4 | .1975 | .0278 | -.1113 | 1 |

For instance, Factor 1 and Factor 2 showed a low correlation (r = 0.11), indicating differing viewpoints on structured support versus mentorship beyond the dissertation. Similarly, Factor 1 and Factor 3 had a moderate correlation (r = 0.20), reflecting some shared emphasis on faculty expertise. The KADE analysis using PCA and Varimax rotation provided a structured, data-driven interpretation of doctoral students’ expectations and experiences with faculty mentoring. The four-factor solution revealed diverse mentoring needs, with implications for faculty development, dissertation chair training, and doctoral program improvements.

Findings

The Q methodology analysis identified four distinct viewpoints among online doctoral students regarding their expectations and experiences of faculty mentoring during the dissertation process. These viewpoints reflect varying mentoring needs, from structured guidance to relational support and accountability.

Factor 1: Structure-Seeking Students

This group, consisting of six students (four just beginning coursework and two who had completed doctoral coursework, including one male and five females), prioritizes clarity, structure, and decisiveness from their dissertation chair. They are not particularly concerned with career guidance or subject-specific mentorship but instead seek a chair who ensures efficient progress and provides a well-defined roadmap for completing the dissertation. They highly value clear and open communication, explicit expectations and deliverables, and a chair who determines when the dissertation is ready for defense. However, they place less emphasis on career support, assistance in selecting committee members, and a chair with deep expertise in their research area. For these students, an effective dissertation chair functions as a project manager, providing structure and decisiveness rather than serving as a mentor beyond the dissertation process.

Factor 2: Relationship-Seeking Students

This group includes six students (one just beginning coursework and five who had completed doctoral coursework, with three males and three females). Notably, the student just beginning coursework had recently started in the current doctoral program but had previously completed all doctoral coursework at another university and was considered ABD (All But Dissertation). Relationship-seeking students desire a supportive and affirming relationship with their dissertation chair, emphasizing a mentoring approach that fosters collaboration, encouragement, and networking opportunities. They value a chair with strong methodological expertise, a positive and affirming relationship, and connections to research networks and resources. Conversely, they place less importance on academic rigor and standards, motivation and perseverance coaching, and help navigating institutional policies. These students expect their dissertation chair to serve as both a research advisor and a mentor, providing guidance while cultivating a sense of professional and academic community.

Factor 3: Direction-Seeking Students

Comprising four students (one just beginning coursework and three who had completed doctoral coursework, with two males and two females), this group values strong, structured guidance from their dissertation chair. They seek direct instruction, clarity in refining their research focus, and assurance that they are ready to defend their dissertation. Unlike those in Factor 2, these students do not prioritize mentorship or networking opportunities; instead, they expect a directive, hands-on leadership style that emphasizes academic progression. Their key priorities include clear, actionable guidance for topic selection and refinement, structured direction throughout the dissertation process, and a chair who makes final determinations about dissertation readiness. They place less emphasis on career support, networking and professional identity development, and assistance with navigating institutional policies. For these students, an ideal dissertation chair acts as an academic strategist, ensuring that their progress remains focused, structured, and efficient without unnecessary distractions.

Factor 4: Accountability-Seeking Students

This factor includes two students just beginning coursework (one male and one female) who highly value consistency, responsiveness, and accountability in their dissertation chair. While they do not expect micromanagement, they want frequent feedback, structured check-ins, and ongoing engagement to keep them on track. Their top priorities include timely feedback to maintain progress, clear guidance on selecting and refining a research topic, and regular check-ins to ensure steady movement through the dissertation. On the other hand, they place less emphasis on committee selection, having a chair with expertise in all aspects of research, and detailed explanations of expectations and deliverables. For these students, the ideal chair is a responsive facilitator who ensures consistent engagement and keeps them on schedule rather than focusing on deep subject-matter expertise.

Discussion

The findings of this study reveal four distinct viewpoints on faculty dissertation mentoring among online doctoral students, highlighting the varied expectations and needs that shape their mentoring experiences. Structure-Seeking Students prioritize clarity, efficiency, and well-defined dissertation roadmaps, favoring faculty who provide structured guidance and decisiveness. These students benefit most from dissertation chairs who provide structured milestone tracking, detailed rubrics, and progress monitoring tools, rather than broader career mentorship. In contrast, Relationship-Seeking students emphasize emotional support, research connections, and mentorship beyond the dissertation process, valuing a chair who fosters collaboration and professional development. This mentoring preference aligns with traditional Ph.D. mentorship models, which have been identified as better serving students in terms of long-term academic and professional success. These students see their dissertation chair as both a mentor and an advisor who fosters collaboration and connects them with research opportunities. To support these students effectively, faculty should be trained in relational mentoring strategies, active listening, and motivational coaching, creating a research environment where students feel supported and engaged.

Direction-Seeking Students require a more hands-on, directive approach from their dissertation chair. Their primary need is structured academic guidance rather than professional mentorship or networking. These students look to their advisors for step-by-step methodological support, clear direction on refining their research focus, and definitive decisions regarding dissertation readiness. Faculty development programs should focus on training dissertation chairs to provide structured research guidance and topic refinement support, while institutions could implement faculty-led research methods workshops tailored to dissertation-stage students. Finally, Accountability-Seeking Students emphasize the importance of consistent engagement, timely feedback, and structured check-ins. While they do not seek micromanagement, they rely on regular interactions with their dissertation chair to stay on track. To meet the needs of these students, faculty could implement strategies for maintaining steady communication, using progress-tracking tools, and implementing scheduled check-ins to ensure ongoing engagement.

Figure 3

Visual Representation of Four Online Doctoral Student Viewpoints

The four-factor solution illustrates the diverse ways in which online doctoral students perceive and experience faculty mentoring. While Structure-Seeking and Direction-Seeking Students (Factors 1 and 3) prioritize efficiency and structured guidance, Relationship-Seeking Students (Factor 2) desire mentorship and professional connections, and Accountability-Seeking Students (Factor 4) focus on consistent engagement and responsiveness. These findings highlight the varied expectations doctoral students bring to the mentoring relationship and emphasize the need for flexible, student-centered approaches to faculty mentoring in online doctoral programs.

These findings align with existing research on online doctoral student dissertation mentorship, reinforcing the importance of faculty engagement, timely feedback, and structured guidance in promoting dissertation completion and student persistence (Siesfeld, 2024; Swanson et al., 2015). Prior studies have highlighted faculty mentors as critical to online doctoral student success, particularly in providing academic and emotional support (Golde, 2005). However, this study extends the literature by offering a more detailed understanding of mentoring viewpoints, demonstrating that students have distinct mentoring preferences rather than a universal set of expectations. Unlike prior studies that broadly categorize faculty mentoring as either effective or ineffective, this study introduces a typology of mentoring preferences, offering a novel framework for faculty development and dissertation chair training. The results suggest that a one-size-fits-all mentoring model is insufficient for supporting online doctoral students, emphasizing the need for flexible, student-centered mentoring strategies.

Given these varying mentoring needs, institutions should establish a structured mentoring framework that allows faculty to assess and tailor their advising styles accordingly. Faculty development programs should include self-assessment tools to help dissertation chairs reflect on their mentoring approaches and adjust their methods to align with different student needs. Additionally, institutions could introduce faculty-student mentoring agreements at the start of the dissertation process, setting clear expectations for communication, feedback, and support. While this study identifies the diverse mentoring perspectives of online doctoral students, it does not address which approach should be used in every context or which is most effective. However, it underscores the importance of adaptive mentoring, where faculty and individual student preferences alignment could increase satisfaction. By implementing an exploration process for students and advisors to understand the students desired needs and the advisors preferred style, institutions could enhance doctoral student satisfaction, increase advisor satisfaction, improve dissertation completion rates, and strengthen faculty-student relationships. Establishing a system where students and faculty are paired based on mentoring preferences, such as structure-seeking, relationship-seeking, direction-seeking, or accountability-seeking could help align expectations with the type of support provided. A well-designed matching process could involve an initial assessment, q-sort (with discussion) or questionnaire where students identify their mentoring needs, allowing institutions to pair them with faculty whose mentoring style best suits their expectations. This approach ensures that students' expectations are heard and then guidance, feedback, and support they require, reducing frustration and increasing persistence. Additionally, institutions can facilitate periodic mentoring check-ins to reassess alignment and allow for adjustments when necessary. By implementing a selection and matching process, institutions can create a more effective and supportive dissertation mentoring experience for online doctoral students. Even if students cannot be matched, they will understand how their advisor operates in the mentoring process. Future research could explore how highly productive and highly effective faculty have mentored.

Theoretical Contributions

This study extends Deci and Ryan’s (1985) Self-Determination Theory (SDT) by demonstrating how doctoral mentoring relationships in online education influence students' motivation, persistence, and academic self-efficacy. The identification of four distinct mentoring preference types (Structure-Seeking, Relationship-Seeking, Direction-Seeking, and Accountability-Seeking Students) adds a nuanced understanding of how autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs manifest in dissertation mentoring. While SDT has traditionally been applied to general student motivation and faculty-student interactions, this study highlights how mentoring styles specifically shape the dissertation experience in online doctoral programs, where faculty engagement is often more limited and self-directed learning is crucial. Furthermore, the study suggests that misalignment between students’ psychological needs and faculty mentoring approaches may contribute to disengagement and attrition, an area that has been underexplored in SDT research. These findings provide a foundation for future studies on tailoring faculty mentoring strategies to different student motivational profiles, reinforcing the importance of adaptive mentorship to support doctoral student success.

The findings of this study can be viewed through the lens of Shulman’s (2005) Signature Pedagogy framework, particularly in the context of dissertation mentoring as a defining pedagogical practice in graduate education. Just as professional disciplines have signature ways of educating and socializing students, faculty mentoring during the dissertation process plays a critical role in shaping doctoral students for future roles as faculty members and scholars. The four distinct viewpoints toward mentoring, Structure-Seeking, Relationship-Seeking, Direction-Seeking, and Accountability-Seeking, illustrate that students have diverse preferences for engaging with faculty mentors and require different types of support. Each preference type reflects a different mentoring approach, corresponding to key elements of signature pedagogy: structured guidance, relational mentorship, cognitive apprenticeship, and formative feedback. Structure-Seeking Students align with a structured apprenticeship model, where faculty provide clear expectations, target dates, and step-by-step guidance to ensure dissertation progress. This approach mirrors the surface structure of signature pedagogy, emphasizing observable instructional strategies such as progress tracking and structured feedback. In contrast, Relationship-Seeking Students prefer a relational mentoring model, where faculty act as coaches and professional guides, fostering connections, emotional support, and building students’ confidence. This mentoring approach provides students with insight into the hidden curriculum of graduate education, where faculty socialize students into scholarly networks and offer professional mentorship beyond dissertation completion.

Similarly, Direction-Seeking Students benefit from cognitive apprenticeship mentoring, where faculty provide hands-on, directive guidance, helping students refine their research focus and develop methodological expertise. This preference reflects deep structure learning, in which students seek structured guidance early on but ultimately transition into independent research scholars. Lastly, Accountability-Seeking Students thrive on consistent engagement, formative feedback, and structured check-ins, aligning with pedagogical models that emphasize external accountability mechanisms to sustain motivation and ensure steady dissertation progress.

Findings further suggest that dissertation mentoring is not a one-size-fits-all practice but rather a flexible and adaptive pedagogical approach that should be tailored to students’ individual needs and career aspirations. Additionally, no single faculty mentor may fully meet a doctoral student’s needs, and students should be encouraged to seek mentorship from multiple sources that complement the style of their primary mentor. Faculty development programs should incorporate mentoring self-assessments to help faculty recognize their dominant mentoring styles and adapt their approaches as needed. Institutions can further enhance dissertation mentoring by implementing formal mentoring agreements, which can establish clearer expectations and communication strategies between faculty and students.

Additionally, professional development workshops should train faculty to recognize diverse student mentoring needs and, when misalignment occurs, guide students toward seeking additional mentorship from other professionals. Establishing formal mentoring networks within doctoral programs may also help students develop a sense of scholarly identity and professional belonging, particularly in online doctoral programs, where students lack informal face-to-face learning experiences that are common in traditional doctoral education.

Implications for Practice

The effectiveness of dissertation mentoring in online doctoral programs depends on faculty and administrators recognizing that students have diverse mentoring needs. A one-size-fits-all approach does not work, as students require varying levels of structure, support, direction, and accountability based on their motivations, work styles, and academic experiences. By tailoring mentoring approaches to these distinct needs, administrators can improve student success, retention, and program efficiency. Structure-Seeking Students (Factor Viewpoint 1) thrive on clarity, efficiency, and decisiveness in the dissertation process. They do not seek career guidance or broad academic mentorship but instead require step-by-step expectations, well-defined benchmarks, and structured feedback to ensure their dissertation moves forward efficiently. To support these students, administrators should standardize dissertation expectations by providing structured milestones, timelines, and checklists and developing clear rubrics and templates to reduce ambiguity. Faculty should focus on efficient, decisive feedback, setting firm deadlines and making clear determinations on dissertation readiness rather than waiting for students to determine their own pace. The priority for these students is clarity and structure, not career coaching. This finding is complimentary to Siesfeld’s (2024) research on why students stay in online doctoral programs based on structured support.

In contrast, Relationship-Seeking Students (Factor Viewpoint 2) desire a supportive and affirming mentorship experience, valuing encouragement, collaboration, and research connections over procedural guidance. These students benefit most from a dissertation chair who fosters engagement, provides affirming feedback, and connects them to relevant research networks. Administrators should encourage faculty to adopt a coaching and mentorship mindset, offering training in relational mentoring strategies such as active listening, emotional intelligence, and motivation techniques. Additionally, creating opportunities for networking and research engagement through faculty-led research groups, conferences, and professional development seminars can strengthen students' academic identities. Faculty working with these students should minimize rigid procedural oversight and focus on mentorship rather than bureaucracy, ensuring students feel supported and connected throughout the dissertation journey. The priority for these students is emotional support and research connections, not procedural guidance.

Direction-Seeking Students (Factor Viewpoint 3) require structured academic direction and decisive guidance on topic selection and research execution. Unlike Factor 2 students, they do not seek mentorship or professional development but instead need focused instruction to complete their dissertation. To support these students, administrators should establish a guided dissertation framework that provides clear step-by-step directives for research topic selection, methodology development, and dissertation structure. Faculty should take a direct and instructional approach, ensuring that students maintain a clear academic path rather than allowing for excessive flexibility. Additionally, faculty mentoring guidelines should emphasize academic progression, research methodology training, and dissertation organization rather than professional networking. Offering faculty-led workshops on research methods, literature review synthesis, and data analysis techniques can provide additional structured support. For these students, the priority is clear academic guidance, not professional development.

Finally, Accountability-Seeking Students (Factor Viewpoint 4) depend on consistent engagement, timely feedback, and structured check-ins to stay on track. These students do not require extensive upfront expectations but need ongoing support and progress monitoring to ensure they maintain dissertation momentum. To meet these needs, administrators should implement required faculty-student check-ins to provide continuous engagement and structured accountability. Faculty should be trained to provide timely feedback and reminders, as delayed responses can lead to frustration and stagnation. Additionally, progress tracking systems, such as dissertation dashboards or structured progress reports, can help students remain accountable. Faculty should be encouraged to check in regularly rather than wait for students to reach out. For these students, the priority is consistent engagement and structured accountability, not upfront expectations. By recognizing whether a student needs structure, emotional support, direction, or accountability, faculty can improve the efficiency and effectiveness of dissertation mentoring. Administrators should provide training, resources, and policies that align with these student-centered mentoring approaches, ensuring that faculty are equipped to meet diverse mentoring needs. A tailored mentoring model will lead to higher retention rates, reduced attrition, and a more supportive dissertation experience for online doctoral students.

Recommendations for Future Research

By reframing dissertation mentoring as a signature pedagogical practice, institutions can enhance doctoral student development, increase dissertation completion rates, and improve the overall faculty-student mentoring experience. Future research should explore how faculty mentors can best balance structured guidance with scholarly autonomy, ensuring that students receive both the direction they need to succeed, and the independence required to develop as researchers. Future research could explore how faculty mentoring styles impact dissertation completion rates and student satisfaction in online doctoral programs. Given that students have distinct mentoring preferences, ranging from structure and direction to relationship-building and accountability, studies could examine how faculty adapt their mentoring approaches and the extent to which these adaptations influence student persistence and dissertation success. Additionally, longitudinal studies could track students from the beginning of their doctoral journey through dissertation completion, identifying whether their mentoring needs evolve over time and how faculty responsiveness contributes to retention and completion outcomes.

Further research should also consider institutional and programmatic factors that shape dissertation mentoring experiences. For example, studies could explore how different university policies, faculty training programs, and dissertation structures influence mentoring effectiveness. Examining best practices for faculty development in online doctoral programs would provide insights into how institutions can better prepare faculty mentors to meet diverse student needs. Additionally, research could investigate how mentoring expectations differ across disciplines, particularly in fields with varying research methodologies and dissertation structures, to determine whether certain mentoring styles are more effective in specific academic domains.

Another promising area for research is the role of technology and online learning platforms in dissertation mentoring. Since online doctoral programs rely on virtual communication, studies could explore the effectiveness of different mentoring formats, such as synchronous video meetings, asynchronous feedback, structured online mentoring groups, and AI-driven dissertation support tools. Research could also assess the impact of institutional support systems, such as writing centers, peer mentoring programs, and dissertation boot camps, in supplementing faculty mentoring.

Additionally, a critical area for further study is how faculty stay current in content knowledge of methods to effectively mentor dissertations. Faculty members often specialize deeply in a particular research method during their own doctoral dissertation but may not consistently engage in ongoing professional development or active research practice post-graduation. Without continuous exposure to new methods, data analysis techniques, and emerging research tools, faculty may struggle to provide comprehensive and up-to-date guidance to doctoral students, particularly in fast-evolving fields. This could create a gap in the expectations of the doctoral student and the ability of the faculty member. Graduate programs could develop training in research methods to share new practices and refresher courses to ensure faculty have access to the knowledge to stay current would help support learning. Additionally, professional organizations or institutions could develop a faculty mentoring network, where dissertation chairs could collaborate, discuss best practices, and discuss challenges. This network could also have professional development. Institutions could provide incentives such as mini-grants, research funds or reduced teaching loads for faculty to actively engage in research training that would result in publication or grant applications.

A study examining how faculty maintain and update their methodological expertise, what professional development opportunities are most effective, and whether institutions provide adequate training and support could help bridge this gap. Understanding the challenges faculty face in staying methodologically current would inform policies that encourage ongoing research engagement, method workshops, and interdisciplinary collaboration to ensure faculty mentors are equipped to guide doctoral students effectively.

Lastly, future research should examine student demographics and external factors that may influence mentoring needs. Investigating whether age, professional background, prior research experience, or cultural expectations shape students’ mentoring preferences could provide a more nuanced understanding of how faculty can personalize their mentoring approaches. Comparative studies between online and traditional doctoral students could also offer insights into whether mentoring needs and challenges differ between virtual and in-person dissertation experiences. By building upon these findings, future research can contribute to the development of evidence-based mentoring practices that enhance doctoral student success, retention, and overall academic experiences in online programs.

Conclusion

This study highlights the diverse mentoring needs of online doctoral students during the dissertation process, emphasizing that faculty mentoring must be adaptable to individual student preferences. The findings suggest that Structure-Seeking Students require clear expectations and efficient guidance, Relationship-Seeking Students need emotional support and research connections, Direction-Seeking Students benefit from structured academic direction, and Accountability-Seeking Students thrive on consistent engagement and timely feedback. Recognizing these distinct needs is essential for faculty mentors and administrators to implement effective strategies that enhance student persistence, dissertation completion, and overall satisfaction in online doctoral programs. Furthermore, the study underscores the importance of faculty development, particularly in maintaining methodological expertise to effectively mentor students. As faculty often specialize deeply in one research method during their own PhD program, they may struggle to stay current without ongoing professional development and active research engagement. Future research should explore how faculty can best maintain and expand their methodological competencies, as well as investigate the institutional factors, technological tools, and demographic influences that shape dissertation mentoring experiences. By fostering evidence-based, student-centered mentoring approaches, online doctoral programs can enhance faculty effectiveness, reduce attrition, and support doctoral candidates in successfully completing their dissertations.

References

Banasick, S. (2023). Ken-Q Analysis (Version 2.0.1) [Computer software]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8310377

Bartlett, J. E., Bartlett, M. E., Dolfi, J. J., Jaeger, A. J., & Chapman, D. D. (2018). Redesigning the education doctorate for community college leaders: Generation, transformation, and use of professional knowledge and practice. Impacting Education: Journal on Transforming Professional Practice, 3(2).

Bartlett, M. E., & Bartlett, James E., II. (2023). Using Q methodology for distance program marketing and recruitment. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 26(3).

Bartlett, M. E., Bartlett II, J. E., & Williams, M. R. (2024). Insights for online program administrators from phd learners’ summer institute residency experiences. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 27(3), n3.

Brown, S. R. (1980). Political Subjectivity: Applications of Q Methodology in Political Science. Yale University Press.

Burrington, D., Madison, R. D., Schmitt, A., & Howell, D. (2022). Student perspectives on dissertation chairs’ mentoring practices in an online practitioner doctoral program. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 25(4), 1-19.

Collins, A., Brown, J. S., & Newman, S. E. (2018). Cognitive apprenticeship: Teaching thFFe crafts of reading, writing, and mathematics. In Knowing, learning, and instruction (pp. 453-494). Routledge.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of research in personality, 19(2), 109-134.

Golde, C. M., & Dore, T. M. (2001). At cross purposes: What the experiences of today's doctoral students reveal about doctoral education.

Golde, C. M. (2005). The role of the department and discipline in doctoral student attrition: Lessons from four departments. The Journal of Higher Education, 76(6), 669-700.

McNeill, L., Beavers-Forrest, B., Rice, M., Benson, A., & Abu, S. (2024). Ph. D. Student Voices: The Highlights and Challenges of Navigating a Hybrid Doctorate. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 27(4), n4.

McKeown, B., & Thomas, D. B. (2013). Q methodology (Vol. 66). Sage publications.

Moses, I. (1985). Student-Advisor Expectation Scales. Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia. Adapted by Kiley, M., & Cadman, K. (1997), Centre for Learning & Teaching, University of Technology, Sydney; further adapted by Golde, C. M. (2010), Stanford University. Retrieved from https://graduatedivision.ucmerced.edu/sites/graduatedivision.ucmerced.edu/files/page/documents/expectation_scales.pdf

Oltman, G., Surface, J. L., & Keiser, K. (2019). Prepare to chair: Leading the dissertation and thesis process. Rowman & Littlefield.

Ramlo, S. E. (2024). Integrated Data Collection in Q Methodology: Using ChatGPT From Concourse to Q-sample to Q-sort. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 15586898241262824.

Ramlo, S. (2025). Examining Subjectivity with Q Methodology. Taylor & Francis.

Ramlo, S. E., & Newman, I. (2011). Q methodology and its position in the mixed methods continuum. Operant Subjectivity, 34(3), 172-191.

Siesfeld, C. A. (2024). Why Students Stay in an Online Doctoral Program: A Phenomenological Study (Doctoral dissertation, University of Dayton).

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational researcher, 15(2), 4-14.

Shulman, L. S. (2005). Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus, 134(3), 52-59.

Shulman, L. (2010). Doctoral education shouldn’t be a marathon. Chronicle of Higher Education, B9-B12.

Stephenson, W. (1953). The Study of Behavior: Q-technique and Its Methodology. University of Chicago Press.

Swanson, K. W., West, J., Carr, S., & Augustine, S. (2015). Supporting dissertation writing using a cognitive apprenticeship model. In Handbook of research on scholarly publishing and research methods (pp. 84-104). IGI Global.

Appendix A: Themed Q Sample

Research Guidance and Expertise

- Provide clear and actionable guidance for selecting and refining a research topic.

- Help the student select committee members.

- Be knowledgeable and able to give advice on the methods employed in the study.

- Have extensive expertise in my field or topic area to offer informed advice.

- Be an expert researcher who can advise on all steps of the research process.

Feedback and Quality Assurance

- Provide feedback within a reasonable and agreed-upon timeframe.

- Offer detailed comments that clarify how to improve my work.

- Provide timely dissertation feedback to keep me on track and feeling supported.

- Critique the quality of the dissertation and give areas for improvement.

- Ensure that feedback focuses on both strengths and areas needing improvement.

Emotional Support and Motivation

- Provide support, understanding, and patience during dissertation challenges.

- Motivate me to persevere through difficult tasks.

- Foster a positive and affirming relationship throughout my dissertation journey.

- Celebrate my accomplishments to build confidence in my progress.

- Provide encouragement and reassurance during setbacks.

Communication and Accessibility

- Be accessible and responsive to emails and meeting requests.

- Provide clear and open communication, which is critical to my progress.

- Clarify expectations and deliverables for every stage of the dissertation process.

- Schedule regular check-ins to help me stay on track.

- Respond promptly to questions and concerns to maintain momentum.

Advocacy and Mentorship

- Advocate for me and help resolve conflicts during the dissertation process with the committee.

- Connect me with resources and people to advance my research and professional identity.

- Help me navigate institutional policies and procedures.

- Serve as a mentor, offering advice on where to present and publish my research.

- Provide guidance on building long-term career aspirations and professional skills.