Abstract

Curriculum mapping can be used to visualize, align, and assess the ability of online degree program graduates to meet stated learning outcomes (Rawle et al., 2017). Though consensus has yet to be established on standardized outcomes for curriculum in some disciplines (e.g., criminal justice), educators remain in charge of preparing current and future practitioners for success. We know measuring student performance is the norm, but a standardized vision of the outcomes being analyzed has yet to be realized. Regardless of the specific outcomes a degree program prepares students for, it seems reasonable that the outcomes would be measured and evaluated by educators and administrators to improve student performance over time. Unfortunately, no standardized recipe for that success exists, especially as instructional delivery shift to online environments and student demographics change. Some disciplines need more consensus on what qualities (outcomes) are most important for career success.

However, once established, the question remains of adequately assessing those outcomes and driving student performance positively. As administrators, we hope our students achieve measurable outcomes to prepare them for their chosen career fields. The question thus remains: How do we ensure the course curriculum adequately addresses stated program outcomes? Internal assessment tools are often used, but this method may not always be enough. The answer may lie with external benchmarking or a similar form of summative assessment, at least during initial curriculum validation. Regardless of the chosen validation strategy, student achievement against those outcomes should be measured.

Summative assessment has proven helpful in benchmarking student performance against learning objectives, though assessments are often only internal, leaving a need for external validation. While the author agrees that learning objectives should be established, an argument is not made about which objectives are most important for criminal justice majors, as is used in the present study. Instead, this research provides a potential framework for improving student performance in meeting program outcomes using an externally validated benchmarking approach for online adult learners in a criminal justice bachelor’s program. Specifically, this research aims to show how external benchmarking was used to revise course curriculum mapping and improve student outcome achievement in an online undergraduate criminal justice program.

Literature Review

The value of learning assessment is a primary focus of higher education institutions, and it is a sensitive process in online learning (Gil-Juarena et al., 2022). According to Gregory (2013), the influence of assessment on teaching design is heavily pronounced in online courses. In some cases, online institutions measure the quality of their assessment strategies by gauging the alignment between course teaching objectives and program outcomes. This process is typically referred to as outcome mapping or curriculum mapping. Where teaching strategies are developed based on stated learning objectives, quality is highest in distance learning (Kirkwood & Price, 2008).

For example, a prepare, practice, perform model where students can practice the skills needed to master specific concepts safely involves a continuous feedback loop ending with student reflections on performance (Sluijsmans et al., 2013; Van Merrienboer & Kirschner, 2017). This curricular approach could allow students to prepare for real-world scenarios in a safe environment with the benefit of hypothetical reflection. Some argue that skill mastery is a persistent problem in higher education (Peddle, 2000), with employers internationally mentioning college graduates' deficits in key competencies (Prikshat et al., 2020).

The criminal justice discipline faces similar challenges in assessing student learning of stated outcomes. As mentioned, the focus of criminal justice degree program objectives has not yet been standardized, but its importance is an attribute agreed upon by scholars and practitioners (Baker et al., 2017). Even in its wavering definitions of standard or quality, criminal justice programs have grown and continue to be popular among college students (Tontodonato, 2006). When the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences discontinued its program certification requirements, other quality assurance methods had to be adopted to capture the evolution of the discipline (Myers, 1994). Though curriculum mapping is a popular improvement tool in higher education institutions, especially in medicine, where quality standards exist, little research exists to show its efficacy in disciplines such as criminal justice, where standards are subjective. This research is designed to provide a measurable output of student learning objectives and program outcomes once defined by the institution, thus filling the research gap.

Curriculum Mapping

Curriculum mapping is an active process that can align curriculum activities and learning outcomes (Kopera-Frye et al., 2008). Additionally, Lam and Tsui (2013) argue that curriculum mapping can be used to map outcomes throughout a course or an entire program, to map course progression, to track the assessment of learning outcomes as part of curricular alignment, and to identify curricular gaps. Curriculum mapping can be used in formalized curriculum review and improvement (Veltri et al., 2011). Interestingly, though the literature is saturated with the positive benefits of curriculum mapping (Harden, 2001; Morehead & LaBeau, 2005; Uchiyma & Radin, 2009), its potential as a tool for curriculum evaluation has yet to be fully utilized (Lam & Tsui, 2016). Considering the popularity and potential of curriculum mapping, it seems reasonable to assess the effectiveness of our curriculum mapping strategy, given the subjective nature of the task. Internal benchmarks must be considered but may not provide a complete assessment picture.

External benchmarking

In higher education, a significant purpose of assessment is executing accountability (Archer, 2017; Capsim, 2020), and is primarily achieved through providing evidence that learning is occurring. As a means of accountability, external benchmarks provide credibility to institutional statements of student outcomes achievement (Guangul et al., 2020).

External benchmarking also gives credibility to a particular curriculum approach when leveraged appropriately. Al-Halwachi (2024) offers several strategies for appropriately leveraging external benchmarking when results differ from internal assessments:

1). Analyze results: Thoroughly examine discrepancies between internal and external assessment results.

2). Review test format and conditions: Differences in test format and conditions can impact student performance.

3). Evaluate content coverage: External benchmarking assessments may be broader in scope than internal assessments, and discrepancies in results can highlight areas of instructional or mapping adjustments.

4). Consider student motivation: External benchmarking assessments may be perceived as “high stakes,” thus impacting student performance.

5). Collaborate with colleagues: Analyzing discrepancies and adjusting instructional approaches should be collaborative.

Curriculum Model

Though no consensus on criminal justice curriculum objectives exists, similarities are evident. Without standardized outcomes, evidence of student achievement on the stated program outcomes becomes more critical for these degree programs. The curriculum in the present study uses program outcomes to define the overall mission and vision of the degree program from a classroom perspective. In other words, the program outcomes drive the learning objectives within each course where applicable. This type of model is more easily managed in an online program where the curriculum is often more standardized across course sections as compared to the traditional classroom. The following passages provide context to the curriculum mapping strategy in the present study.

Program Outcomes

Specifically, in this study, the program outcomes for the criminal justice bachelor program are as follows:

- Criminological theory - Use biological, sociological, and psychological theories of crime to understand the reasons individuals commit crimes.

- Law - Apply the principles of criminal law and civil liabilities to keep officers and agencies from committing criminal acts and violating civil liberties.

- Research Methods - Use scientific methods to make professional and logical decisions.

- Leadership - Build relationships within the community by understanding organizational culture, community relations, and theories of behavior.

- Operations - Use available resources to make sound operational decisions for the criminal justice agency.

- Technology - Apply new technology to improve the operations within a criminal justice agency.

- Internationalism - Understand and evaluate worldwide criminal justice systems and enterprises.

A cross-section of faculty, administrators, and other subject matter experts create program outcomes at the institution. Though subjective, the program outcomes are revisited and revised consistently across a three-year course revision cycle to ensure currency and relevance to the field of study. Administrators use these elements to help faculty and subject matter experts guide course curriculum decisions and create course-level outcomes and assessments.

Though somewhat cross-disciplinary with elements of legal studies and social science, the program outcomes in this example heavily focus on criminal justice operations and making sound leadership decisions. This focus is not surprising, given the faculty and subject matter expert demographics. Courses are designed by faculty and practitioners with decades of experience in the field and the classroom, many of whom hold or have held supervisory roles in law enforcement and corrections. This serves the student population well, considering the institution caters primarily to working adults, many with their own career experience. The program is designed to educate those with criminal justice experience looking to advance their career and those looking to enter the field. Administratively, the program outcomes define what competencies students gain during their degree program. Thus, the program outcomes give administrators a focal point for potential student and employer marketing efforts.

Outcome Mapping

Similarly, course learning outcomes are developed within the framework of the program outcomes when courses are created and revised. Once the learning objectives are defined, the course content is created. The curriculum includes several student activity and interaction elements, including discussion boards, live Zoom seminars, quizzes, learning activities, and assignments. More importantly, the course-level assessments, measured by assignment performance, address the critical subject matter of the course content while also mapping directly to the program outcomes.

For example, a learning objective in an introductory criminal justice course might be identifying the constitutional right to due process. This objective could relate directly to the program outcomes of law and operations. Similarly, in an upper-level criminal justice leadership course, a course outcome might be to analyze the decision-making process within a criminal justice organization. This objective relates to the leadership and operations program outcomes.

This curriculum design maps course objectives to the program outcomes to measure student performance against these competencies. Administrators can thus gauge the proficiency level of program graduates in acquiring these skills. Ideally, graduates will be well-versed, having mastered or nearly mastered each outcome. As outcomes are revised during the three-year revision cycle, a mapping spreadsheet correlates where course learning objectives address program outcomes (Table 1). Notably, each course outcome has Bloom’s taxonomy classification or level (e.g., knowledge). The aim is to thoroughly immerse program outcome concepts throughout the degree program course curriculum. This ensures students are fully exposed to them, which is why program outcomes are general, allowing more flexibility in course content.

Table 1: Course outcome to program outcome mapping example

| Criminology Theory: Use biological, sociological, and psychological theories to understand the reasons individuals commit criminal acts. | Law: Apply the principles of criminal law and civil liabilities to keep officers and agencies from committing criminal acts and violating civil liabilities. | Research Methods: Use scientific methods to make professional and logical decisions. | Leadership: Build relationships within the community by understanding organizational culture, community relations, and theories of behavior. | Operations: Use available resources to make sound operational decisions for the criminal justice agency. | Technology: Apply new technology to improve the operations within a criminal justice agency. | Internationalism: Understand and evaluate worldwide criminal justice systems and enterprises. | |||

| CJ101-1 | Identify the elements that constitute the three core components of the criminal justice system. | 1: Knowledge | 1 | 1 | |||||

| CJ101-2 | Explain how the five core operational strategies are used to reach law goals. | 2: Comprehension | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| CJ101-3 | Identify the constitutional right to due process. | 1: Knowledge | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| CJ101-4 | Describe how the 4th Amendment applies to search and seizure as related to legal precedent. | 2: Comprehension | 1 | 1 | |||||

| CJ101-5 | Examine the role of the correctional system in sentencing offenders. | 3: Application | 1 | ||||||

In this example, the introductory course has five objectives tied to one or more of seven program outcomes. As noted, each course objective does not need to tie to a program outcome since the goal is for those outcomes to be measured across the entire degree program of course requirements. Some program outcomes may be covered less in this course but will be made up for in other courses. Conversely, each course learning objective is thoroughly covered during the ten-week term.

Curriculum Design

One of the benefits (and consequences) of many online courses is the level of familiarity across courses and class sections. Due to a standardized learning management system, the design of each course shell feels comfortable for faculty and students. Course similarities at the institution in the present study include reading materials and web resources, discussion boards, weekly live seminars, learning activities, quizzes, exams, and assignments. Assignments could be written essays or research papers, PowerPoint assignments, group presentations, or video responses. The standardization aspect of the course shell leaves little to be desired for some critics.

However, faculty are given freedom within the course shell to make the classroom their own. For example, additional discussion questions can be created, and seminar discussions are guided by the instructor based on personal experience. Some faculty expand the confines of the seminar topic to illustrate the subject matter in real time by conducting mock crime scene investigations or court trials. For all the concerns about standardization, the limitations seem minimal when the faculty member fully integrates technological tools. Much like the traditional classroom, interactive time with students is indeed what one makes it.

Learning activities allow students to practice the material before gauging their performance by completing the assessment. Activities may be scenario-based, fill-in-the-blank responses, repeatable quizzes, or other practice activities. The curriculum follows a prepare, practice, perform model where students prepare for the assessment by reading from textbooks and other resources. Then, students practice the material through learning activities and ungraded tasks. Finally, students perform the material by submitting the assessment, which is directly tied to a course learning outcome. Again, though typically a written assignment or research paper, assessments may also be narrated PowerPoint presentations, video responses, and group presentations. The latter options have recently gained more popularity at the institution in this study, given the rise of artificial intelligence and machine-generated written work. Though intriguing, that discussion is beyond the scope of the current work. Student performance against stated course objectives is then measured through course-level assessment scores.

Internal Benchmarks - Course Level Assessment Scores

In addition to grades, where assessments are scored on a rubric-based percentage score (0-100%), the institution also benchmarks proficiency level against the course level objectives by having faculty calculate a course-level assessment (CLA) score. CLAs are also scored by rubrics but do not include elements such as late point deductions or template formatting deductions. Instead, the CLA rubrics are focused on the extent to which the student covers the subject matter in a clearly communicated manner outside of writing style errors (Table 2).

Table 2 - CLA rubric example from introductory criminal justice course

CJ101-1: Identify the elements that constitute the three core components of the criminal justice system. Unit 1 Assignment | ||||||

No Progress | Introductory | Emergent | Practiced | Proficient | Mastery | |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Identify | Student work demonstrates no understanding or progress towards achievement of this outcome. | Student attempts to identify three core components of the criminal justice system but is unsuccessful. | Left blank intentionally for instructor discretion. | Student identifies one core component of the criminal justice system. | Student identifies two core components of the criminal justice system. | Student identifies three core components of the criminal justice system. |

| Discuss | Student work demonstrates no understanding or progress towards achievement of this outcome. | Student work discusses the material for one question on the component demonstrating critical thinking skills. | Student work discusses the material for two questions on the components demonstrating critical thinking skills. | Student work discusses the material for three questions on the components demonstrating critical thinking skills. | Student work discusses the material for four questions on the components demonstrating critical thinking skills. | Student work discusses the material for five questions on the components demonstrating critical thinking skills. |

A heavy reliance on Bloom’s taxonomy and the verbs used in the various classifications drives the creation of the CLA rubric. The instructor completes a clickable rubric for each student submission using the zero to five scale. An overall CLA score is automatically computed for each student, and the data is collected for future use by faculty and administrators during the curriculum planning and revision process. CLA scores are also aggregated to provide course-level data. Faculty and administrators use this data to make decisions about course design and assessment application. Generally, a CLA score below four may indicate a need for further course investigation and potential improvement.

Thus, CLA scores are used as the institutions’ internal assignment and course performance benchmarks. With most courses producing CLA scores higher than 4.2, it was comfortable to say that students readily met course and program outcomes. This is true to an extent, though verifying our internally benchmarked success with an external performance measure seemed beneficial.

External Benchmarks

External benchmarking allowed for additional validity in whether or not students met stated program outcomes. The internal benchmark CLA scores were high, denoting a solid curriculum model and student proficiency in learning objectives. However, the initial external benchmarking analysis produced a different picture (Table 3).

Table 3 - Initial external benchmarking results

| Assessment Area | Study Institution | Other Online Institutions | Campus-based institutions |

| Administration of Justice | 63.41% | 65.78% | 63.52% |

| Courts | 59.15% | 64.98% | 65.87% |

| Criminological Theory | 51.71% | 56.81% | 54.70% |

| Ethics and Diversity | 53.17% | 56.51% | 56.32% |

| Research and Analytical Skills | 46.10% | 47.18% | 41.61% |

| Total | 54.71% | 58.25% | 56.40% |

The tool used for external benchmarking is the Peregrine assessment for criminal justice majors. This tool was selected primarily because of the similarities between the available assessment areas and the program outcomes for the undergraduate criminal justice program at the study institution. The Peregrine exam is a multiple-choice test addressing assessment areas chosen by the institution. Students complete the exam as part of the bachelor’s capstone course and receive a weighted assignment grade based on the assessment score. Peregrine exams are graded on a curve based on comparative data. The data can be used to compare scores across institutional types, as shown in Table 1. This study compares the study institution to other online and campus-based institutions. Initial results showed weaker proficiency in stated program outcomes than both groups.

Methodology

Using the external benchmarking leveraging strategy discussed by Al-Halwachi (2024), the researcher considered the following:

1). Analyze results - The initial external benchmarking results suggested noticeable discrepancies compared to the internal assessment (CLA) scores. This suggested that a closer look at the remaining considerations described by Al-Halwachi (2024) was necessary.

2). Review test format and conditions - This consideration was deemed acceptable as the test is administered in the same learning management system format as other assignments and learning activities.

3). Evaluate content coverage - Not all courses addressed each program outcome. This could have been an impacting factor in the discrepancy between internal and external assessment results.

4). Consider student motivation - Educators must consider how to take pressure off the assessment process.

5). Collaborate with colleagues - Given the collaborative nature of the curriculum development process, this consideration was deemed acceptable and would continue.

First, content coverage was an area of concern. In the initial model, as described, not all course curricula mapped directly to program outcomes. Simultaneously, the collaborative group involved in the curriculum process determined that not all course curricula needed to map directly to program outcomes. For example, a corrections elective on prisons in the United States may not directly cover internationalism. The decision was made to have all non-elective core major course requirements, approximately fifty percent of the degree program, map directly to the program outcomes. Specifically, throughout each major requirement course, each program outcome was mapped through the curriculum at least once. In other words, students were now exposed to a course curriculum covering each stated program outcome saturated throughout at least fifty percent of the degree program. Faculty and course developers revised the course curriculum to ensure major requirements mapped to each program outcome. The course revisions took place over a three-year revision cycle. The assessments used to measure the course learning objectives mapped to the program outcomes ranged from written assignments to video presentations. The idea was that student outcomes would improve through greater exposure to those outcomes throughout the program. It also provided a reasonable basis for determining if the curriculum mapping was accurate.

Additionally, student motivation was worth addressing. After the initial results, the decision was made for students to earn points for completing the exam rather than based on their exam scores. This strategy helped ease the pressure on students, at least anecdotally.

Results

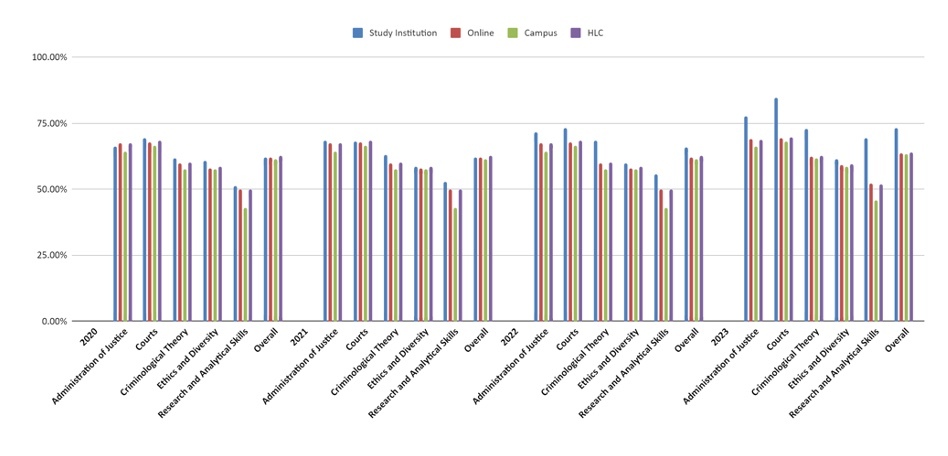

Given the discrepancy between internal and external benchmarking results, the researcher determined that the curriculum model for measuring CLAs and the curriculum mapping strategy was appropriate. However, based on the external benchmarking analysis, the extent to which students were versed in program outcomes or assessment areas was comparatively lacking. The decision was made to focus learning objectives more heavily on program outcomes throughout the degree program curriculum rather than focusing them heavily in specific courses. The same overarching curriculum measurement model was retained based on internal benchmarks, but the frequency with which students were exposed to essential elements of those outcomes increased. Additionally, faculty doubled down on their practitioner and classroom experience, enhancing the classroom with a heavier emphasis on scenario-based learning. Over the next three-year revision cycle, students would be continuously exposed to learning objectives related to career and program outcomes to improve their proficiencies (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Comparative analysis across a three-year revision cycle

To expand the comparative analysis, the researcher added a category for Higher Learning Commission (HLC) accredited institutions in addition to other online and campus-based institutions. The results show continuous improvement across program outcomes for the revision cycle, with the study institution outpacing all comparative groups over time. As the revision cycle progresses, the study institution outperforms the comparative groups across all assessment areas, widening the student performance gap. Additionally, internal benchmarking improved during this period, with the overall CLA score average increasing from 4.25 to 4.46. Using external assessment to inform the curriculum revision cycle and mapping process proved beneficial according to internal and external performance measures.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Though internal benchmarks showed promising results when implementing a curriculum outcome measurement model, external benchmarking allowed for comparative analysis. The analysis showed room for improvement across stated program outcomes, while internal assessment gave credence to the validity of the measurement model. By seeking external validity, the curriculum for an entire degree program could be focused during a regular revision cycle, thus alleviating administrative confusion or potential lack of direction. When a curriculum model is implemented, ensuring appropriate success measures are in place and are used to guide the model accordingly can ultimately determine a degree program’s fate. In this study, curriculum mapping validated through internal and external benchmarking proved effective.

Agreement exists in favor of well-defined learning objectives. Nevertheless, no consensus has been reached on standardized outcomes in several disciplines. Thus, gauging student performance in the identified program goals is critical, particularly in online environments. Internal benchmarking provides a solid foundation for validating a curriculum model, though this research has provided some potential benefits of adding external benchmarking to increase program effectiveness. Beyond general marketing campaigns proclaiming student satisfaction and employability, external validation of student performance provides data to support student achievement against a defined curricular focus.

References

Al-Halwachi, A. (2024). Leveraging external benchmarking assessments to inform planning. Retrieved from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse...

Archer, E. (2017). The assessment purpose triangle: Balancing the purposes of educational assessment. Frontiers in Education, 2(41)

Baker, W.M., Holcomb, J.E., and Baker, D.B. (2016). An assessment of the relative importance of criminal justice learning objectives. Journal of Criminal Justice Education 28(1), 129-148.

Capsim. (2020). The five levels of assessment in higher education. Retrieved from https://www.capsim.com/blog/th...

Gil-Jaurena, I., Dominguez-Figaredo, D., and Ballesteros-Velazquez, B. (2022). Learning outcomes based assessment in distance higher education. A case study. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance, and E-Learning, 37(2), 193-208.

Gregory, V.L. (2013). Assessment of student learning outcomes in distance education. In A. Sigal (Ed.), Advancing library education: Technological innovation and instructional design (pp. 172-182).

Guangul, F.M., Suhail, A.H., Khalit, M.I., & Khidhir, B.A. (2020). Challenges of remote assessment in higher education in the context of COVID-19: A case study of Middle East College. Educ Access Eval Account, 32(4), 519-535.

Harden, R.M. (2001). AMEE Guide No. 21: Curriculum mapping: A tool for transparent and authentic teaching and learning. Medical Teacher, 23(2), 123-137.

Kirkwood, A., and Price, L. (2008). Assessment and student learning: A fundamental relationship and the role of information and communication technologies. Open Learning, 23(1), 5-16.

Kopera-Frye, K., Mahaffy, J., and Svare, G.M. (2008). The map to curriculum alignment and improvement. Collected Essays on Learning and Teaching, 1, 8-14.

Lam, B.H., and Tsui, K.T. (2013). Examining the alignment of subject learning outcomes and course curricula through curriculum mapping. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38(12), 97-119.

Lam, B.H., and Tsui, K.T. (2014). Curriculum mapping as deliberation-examining the alignment of subject learning outcomes and course curricula. Studies in Higher Education, 41(8), 1371-1388.

Morehead, P., and LaBeau, B. (2005). Successful curriculum mapping: Fostering smooth technology integration. Learning and Leading with Technology, 32(4), 12-17.

Myers, L.B. (1994). The evaluation of criminal justice programs: Assessment of evolving standards in context. Journal of Criminal Justice Education 5(1), 31-48.

Peddle, M.J. (2000). Frustration at the factory: Employer perceptions of workforce deficiencies and training needs. The Journal of Regional Analysis & Policy, 30(1).

Prikshat, V., Montague, A., Connell, J., & Burgess, J. (2020). Australian graduates’ work readiness: Deficiencies, causes and potential solutions. Higher Education, skills, and Work-Based Learning, 10(2), 369-386.

Rawle, F., Bowen, T., Murck, B., & Hong, R. (2017). Curriculum mapping across the disciplines: Differences, approaches, and strategies. Empowering Learners, Effecting Change, (10), 75-88.

Sluijsmans, D., Joosten-ten Brinke, D., & Van der Vleuten, C. (2013). Toetsen met leerwaarde [Assessments with value for learning]. NWO.

Uchiyama, K.P., and Radin, J.L. (2009). Curriculum mapping in higher education: A vehicle for collaboration. Innovative Higher Education, 33(4), 271-280.

Van der Kleij, F.M., Feskens, R.C.W., & Eggen, T.J.H.M. (2015). Effects of feedback in a computer-based learning environment on students’ learning outcomes: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 85(4), 475-511.

Veltri, N.F., Webb. H.W., Matveev, A.G. & Zapatero, E.G. (2011). Curriculum mapping as a tool for continuous improvement of IS curriculum. Journal of Information Systems Education. 22(1), 31-42.