Abstract

Background

While surveys that measure readiness for online learning are not new, gaps exists in ensuring such tools are student-centered and directly inform student support strategies. Thus, a new orientation support program was creating for all incoming online students at a large public university. The Online Readiness and Student Success Assessment (ORSSA) was presented in an interactive video survey format asking open-ended questions about the online skills, needs and preferences of learners. Based on ORSSA responses, students are provided a customized online success plan of bookmarks, online resources and links to university support services . This paper analyzes the initial results from the first 392 participants in the ORSSA survey, with an eye towards validating the proprietary ORSSA survey and identifying new findings for student success plans for online learning.

Methods

Qualitative survey data was analyzed to provide a contextual understanding of the following research questions:

1. What challenges with online learning do these students identify?

2. What opportunities for support do students indicate that they need to prepare them for online learning?

Results and Implications

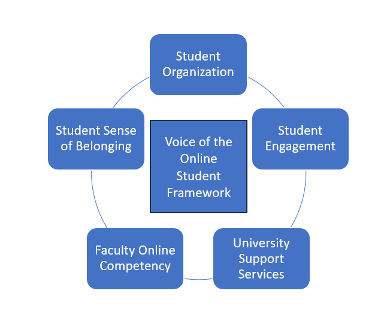

A holistic online student success framework comprised of five elements that emerged from ORSSA survey analysis is proposed. This framework is entirely based on the open-ended responses (voices) of incoming students, and identifies the support tools, resources and services that students feel they need to be successful in their online learning programs. The five elements are: student organization, faculty online competency, student feeling of belonging, university support services and student engagement. Recommendations and examples of how university administration can implement and deliver these five elements are proposed.

Keywords

Online Readiness, Learning Support, Student Success, Online Support, Online Success, Online Student Needs, Online Learning Skills, University Support Services, Online Student Engagement, Online Student Belonging.

Manuscript

Successful online students exhibit a variety of skills, from proficiency at multitasking, a goal-oriented personality, and the ability to work individually and collaboratively (Brindley, 2014), to self-directed learning and online self-efficacy (Karatas & Arpacı, 2021), to writing and computer skills (Landrum, 2020). However, many students enter online programs without these skills and encounter numerous challenges and barriers in virtual learning environments (Martin & Bollinger, 2018). Holistic student success programs and student support mechanisms can be essential for overcoming these challenges and ensuring success and engagement in online learning, particularly in university settings (Muljana & Luo, 2019). Student success programs for the retention of online learners, however, are rarely customized to suit an online learner’s individualized needs (Kember et al., 2023). This can lead to gaps in the academic, technical, and motivational skills of learners. In addition, little or no evaluative research has been performed to examine the effectiveness of online student support mechanisms, including how and when they are delivered (Rotar, 2022). Universities need to develop customized student supports for online learners based on their online readiness skills and evaluate and adapt these programs based on student input. This begins with online student readiness surveys that accurately measure the online learning skills, preferences and needs of incoming students.

While online readiness surveys are absent altogether at many universities, the most common format of currently used online readiness assessments currently measure student agreement with a series of closed questions (typically yes/no or Likert scale) based on pre-determined themes of online student skills rather than taking the approach to inform which university supports could develop online learning skills. Thus, this paper explores an innovative student readiness assessment that includes open ended questions, which help center student voices and minimize bias. Based on the findings of a pilot study of this instrument, practical implications for university administration and student support are explored.

The Online Readiness and Student Success Assessment (ORSSA) is an online survey that is completed during orientation by all incoming students (both graduate and undergraduate) that are enrolled in an online degree or certificate program from the eLearning portfolio at the University. The ORSSA survey was developed after a comprehensive review of the research literature for online learning readiness assessments by the research team and makes a unique contribution to the field because this open-ended data collection tool is incorporated into a larger student success plan. The student experience while taking the ORSSA includes the following personalized features: video introductions highlighting the importance of each section of the survey, a bookmark feature that helps students identify and receive resources for their areas of need, a customized personal success plan of online support services that is emailed directly to each student, and access to a comprehensive resource of online learning best practices and recommendations.

ORSSA research will serve three distinct purposes that guide the research questions in this study, and all three focus on ensuring student success in online and hybrid learning environments. The purposes include allowing students to self-identify their incoming online learning skills, improving the online learning experience for students by providing customized orientation materials based on their responses, and generating recommendations for instructors and universities on best practices for teaching, engaging, and supporting students in online courses. The aim of this study was to identify online learning student success services and how university leadership can deliver these services in an effective manner to promote student development.

Literature Review

The literature review examined four topics to highlight both the need and impact of the ORSSA project and its place in research literature.

Surveys Should Inform Student Needs

The results of online readiness surveys reveal many facets of online student preparedness and online surveys enable students to recognize their strengths and weaknesses (Cheon et al. 2021). Some instruments provide instant feedback, and learners can use this information to increase their proficiency and avoid challenges that prevent them from being successful online learners (Doe, 2017). Other surveys offer online tips or guidelines to improve those areas of weakness (Cheon et al., 2021). In one study, a student’s demographics and preferred technology responses pointed to a need for adaptive, personalized online learning systems (Firat & Bozkurt, 2020). Yu (2018) calls on educators and universities to measure student’s online readiness by examining their social, technical and communication competencies and implement resources that are customized to their identified needs.

In addition to identifying online learning student needs, the cumulative results of readiness surveys inform orientation and training activities for online students (Martin et al., 2020) and determine general areas of weakness or resources that could be provided based on the readiness data of specific colleges (Cheon et al., 2021). One scoping review over online learning evidence-based practices specific to the online environment included the use of user-friendly technology tools, orientation for online instruction, and support of digital literacy in improving online course success and student satisfaction, among others (Lockman & Schirmer, 2020). However, Yu (2018) found that computer and technical skills were a significant factor in affecting online learning experiences but did not guarantee a better learning experience.

The results of online readiness surveys highlighted how instructors play a significant role in the learning process of online students. Positive reinforcement and increased communication from faculty (Chung et al., 2020) as well as meaningful support (Cheon et al., 2021) were necessary for improved outcomes in online learners Furthermore, online educators should reassure less technology-ready students, as those with lower technology exhibited reduced self-efficacy (Warden et al., 2022).

Ultimately, the goal of online readiness tools is to provide more effective interventions that can be developed to help learners succeed (Chien et al., 2022) because online learning efficacy significantly predicts academic performance (Joosten & Cusatis, 2020). Generalized, overarching orientation resources need to be replaced by student-specific online success plans and targeted advice to increase technological competence and confidence in online learners. While a plethora of research exists surrounding the creation and validation of online readiness surveys, further research can better inform efforts to center student perspectives, analyze survey results and implement targeted student support strategies.

Developing Institutional Supports Based on Online Student Needs

Rotar (2022) suggests a process embedding student support interventions into orientation and student success programs. Is proposes a series of supports across a learning cycle of five phase. The Intake phase includes advising prior to enrollment and the Intervention phase identifies at-risk students, provides early interventions and is proactive with support and outreach. The Support phase develops student skills with personal counseling and fosters a sense of community while the Transition phase provides a transition to higher education or the workforce. Finally, the evaluation phase offers self-evaluation tools and surveys on student perspectives.

The entire validation process begins with the intake and intervention phase, where universities identify what students need and plan early interventions, then continue with the support phase consisting of online resources and administrative supports for students. This study focuses on student data that is collected during online orientation in the intake phase and utilizes the voice of the students and their identified needs to propose content and support services that can be provided in the intervention and support phases.

Current State of Online Readiness Assessments and Need for Student Voice

A survey of online university websites reveals that over 40 universities in the United States are currently advertising online readiness surveys on their school websites. This is a small fraction of U.S. universities that offer online programs. Additionally, the yearly report by Quality Matters (Garrett et al., 2023) identified that less than 21% of the 276 schools surveyed have required online orientation programs for students to complete prior to commencing classes. The report suggests that there is a substantial need for the expansion of institutional implementation of online orientation surveys and programs in order to identify and address students’ online learning needs.

A weakness of online readiness assessments is that they have historically been developed based on a set of pre-determined themes or categories and ask closed or Likert-scale questions to measure the student’s agreement with a statement. These began with a foundational online readiness study by Warner et al. (1998) that identified three themes for online readiness: student preferences for online delivery methods, student confidence in using online tools and communications, and the ability to engage in autonomous learning. Online readiness assessments have grown to include common themes such as technical competency and knowledge (Hung et al., 2010), self-directed learning (Atkinson et al., 2012), learning styles and motivation (Bryant & Atkins, 2013), family and peer support (Nwagwu, 2020), and digital literacy (Adams et al., 2022). While being student-centered is a guiding philosophy for many programs, this sentiment is not reflected in surveys that only allow pre-determined option choices.

Current online readiness assessments have focused on measuring student self-efficacy (or belief in their abilities to succeed in online environments) in addition to self-management and technical skills (Sun & Rogers, 2020). While attempting to develop a new form of online readiness survey tool focused on measuring and promoting student self-efficacy and control of their learning journey, Dello Stritto et al. (2023) identified online readiness assessments as critical to understanding what specific resources are required to support student success, as well as a method to engage students with customized interventions based on their responses. Online readiness assessments are rarely, if ever, linked to student success programs. There is a need for more surveys to include open-ended questions where students can identify their own online learning strengths, weaknesses and needs for university supports. The ORSSA survey in this study begins with a series of open-ended questions prior to the commencement of the Likert questions, giving students the opportunity to provide un-biases and personalized responses as to their readiness for online learning.

Methods

Study Approach

The ORSAA survey collected both quantitative (reported in a separate manuscript) and qualitative data. This study employed a qualitative descriptive research design to explore participants’ responses to the qualitative questions in the ORSSA survey. The qualitative data were analyzed to provide a more detailed and contextual understanding of the students’ self-identified online learning strengths, weaknesses and needs for university support based on the following research questions:

- What advantages does online learning provide for incoming university students?

- What challenges with online learning do these students identify?

- What opportunities for support do students indicate that they need to prepare them for online learning?

Qualitative description is an appropriate method when researchers want to provide a straightforward description and to gain insights from participants about the phenomenon (Kim et al., 2017). The open-ended questions on the ORSSA survey were used as the source for the data in this paper to provide an unfiltered, unbiased account of the online learning experience of first-year university students.

Participant Recruitment

This Institutional Review Board approved study was conducted at a large public university in the southwestern United States. All incoming online students are required to participate in’s six online orientation modules, but participation in the study was voluntary and not linked to any course or credit. The fifth module included the ORSSA survey with an online consent page where students are provided with details of the research study and could give their consent. Students who refused consent could still participate in the ORSSA survey, but their data was not collected. Data were collected from incoming online students from January 2, 2023, through October 10, 2023. Study inclusion criteria included any student (undergraduate or graduate) pursuing and online certificate or degree program at the university over the age of 18.

Instruments

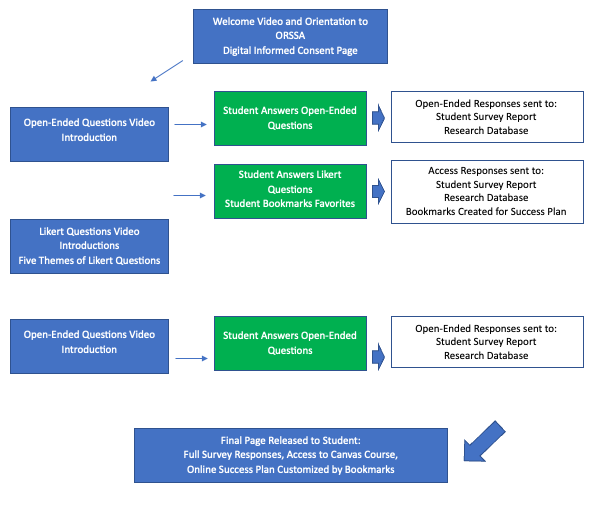

All data were collected from the ORSSA survey, which was delivered online and consisted of a series of 5-point Likert scale questions based on five main themes: access to technology, technology skills, learning preferences, learning skills and learning organization. The survey also began and ended with open-ended questions to gauge each student’s comfort with online learning and anything they might find challenging by studying in an online environment. The open-ended questions and five themes are introduced and explained via a video host. A copy of the ORSSA survey can be found in Appendix I. The process of student participation and data collection in the ORSSA survey can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Process of ORSSA Student Participation and Data Collection

Data Analysis

First, the qualitative data from the 396 participants was reviewed for completeness which resulted in the removal of 4 participants who did not answer the short answer questions, leaving a sample of n =392. Continuous demographic variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation, and discrete parameters are reported as n and percent (%). The student assignment responses were deidentified and stored in a dual authenticated, password protected OneDrive file accessible only by the research team.

Reflexive thematic analysis was used to analyze the short-answer qualitative data. Reflexive thematic analysis is a flexible, interpretative qualitative data analysis approach that guides the emergence and identification of themes in a set of text-based data (Clarke et al., 2015). After reading through the content several times to identify words or phrases that closely related to the aim of the research questions, two of the individual researchers reviewed and coded the responses for each study question and individually analyzed these phrases and summarized them into codes. Patterns emerged from these codes, and a list of themes was created. The research team met together on several occasions to engage in a robust discussion over the themes and creation of sub-themes. Once agreed upon themes emerged, this inductive approach was complete. An audit trail was created to illustrate how the themes were organized, sample quotes from participant were selected, and the results section was complete.

Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) criteria for rigor were applied in this study, including credibility, confirmability, and transferability. Using three individuals to review and engage with the qualitative data to support credibility. The audit trail and codebooks utilized by the research team offers evidence of confirmability, and the incorporation of relevant student quotes allow the readers to assess the potential transferability of the findings. Because most of the students were from social work and nursing, having two members of the research team with more than 20 combined years of working with students in these fields further supports the rigor of the analysis.

Results

Demographic Information

Three hundred and ninety-two incoming online students at the University took part in this study. The students were predominantly female (86.7%) and were primarily studying either Nursing (71.4%) or Social Work (20.2%). There were a variety of ethnicities identified in the student participants, with 19.9% Black/African American, 32.9% Hispanic/Latino and 37.2% White. Over half of the students identified as first-generation university students (53.8%). Detailed demographic data can be found in Table 1.

Table 1

Participant Demographic Information and Online Learning Experience

| Gender | Frequency | Percentage |

| Male | 52 | 13.3 |

| Female | 340 | 86.7 |

| Online Learning Experience | ||

| None | 23 | 5.9 |

| 1-2 Courses | 24 | 6.1 |

| 3-9 Courses (under 2 semesters) | 117 | 29.9 |

| 10+ Courses (2 semesters or more) | 184 | 46.9 |

| Not Indicated | 44 | 11.2 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 | 0.3 |

| Asian | 19 | 4.8 |

| Black/African American | 78 | 19.9 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 129 | 32.9 |

| Multiple Ethnicities | 9 | 2.3 |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.3 |

| Not Specified | 9 | 2.3 |

| White | 146 | 37.2 |

| Academic Program | ||

| Doctoral | 3 | 0.8 |

| Graduate Certificate | 7 | 1.8 |

| Masters | 122 | 31.1 |

| Second Baccalaureate | 57 | 14.5 |

| Undergraduate | 203 | 51.8 |

| College | ||

| College of Architecture, Planning & Public Affairs | 3 | 0.8 |

| College of Nursing & Health Innovation | 280 | 71.4 |

| College of Business | 6 | 1.5 |

| College of Education | 20 | 5.1 |

| College of Liberal Arts | 4 | 1.0 |

| School of Social Work | 79 | 20.2 |

| First Generation University Student | ||

| Yes | 211 | 53.8 |

| No | 181 | 46.2 |

Qualitative Results

The main purpose of this paper was to examine the rich data from the open-ended responses on the ORSSA survey. Since participants answered these questions prior to answering the five themes of Likert questions, their responses were not biased by topics in the ORSSA framework. The three open-ended questions were:

- The top three reasons online learning is good fit for me are…

- My top three challenges or concerns with online learning are…

- What supports or services would you like the university to provide to facilitate your online learning experience?

Qualitative results are discussed into the emerging themes identified in the qualitative coding of the open-ended responses.

Advantages of Online Learning for Incoming Students

Flexibility and Convenience

In analyzing responses to the question, “What are the top three reasons you are pursuing online learning” a prominent theme emerged surrounding the flexibility of remote learning. A substantial number of respondents (n=265) expressed appreciation for the convenience and flexibility that attending school online offers. These sentiments were summed up with the participant response that online learning affords them the opportunity to “to balance work, education, and personal life.” Within this broader theme of flexibility, several subthemes emerged.

Geographical Equity. Virtual learning means the classroom can extend beyond geographical boundaries, enabling individuals to study from any location. Many respondents noted that they live far from the physical campus, so coming in person would not be possible. Thus, offering fully online programs expands learner choice by giving them more options. Even for students that live within a reasonable driving distance of campus, learning online offers the convenience of “no driving or getting stuck in traffic,” with one participant noting “I don't have to fight traffic and weather driving to classes”. Several students also mentioned that the cost savings from not spending money on gas was an important factor. Finally, a number of learners discussed not having access to reliable transportation, saying for instance, “I don't have to worry about finding a way to campus.”

Parenting and Family Caregiving. A common theme that emerged from survey responses was that online courses make it possible for students with caregiving responsibilities to learn while maintaining their family obligations. To illustrate, one student stated, “I have a toddler, so making classes would be a bit harder”, while another participant similarly shared that because online learning is an option, “I don't have to arrange childcare to attend a class”. While childrearing was a common responsibility among survey respondents, some students also discussed their commitments to caring for aging family members, with one saying, “I am sole care giver for my 87-year mother who also lives with me.” Responses made it clear that opportunities to learn online are crucial for students with family caregiving duties.

Accommodating Work Schedules. Results indicate that a significant benefit of online learning is that students can study at their own pace, and during their preferred hours. This was particularly important to students who maintain employment during their studies, with one participant stating that learning online “gives me the flexibility that I need as a working professional.” Many students echoed the sentiment that “I have a full-time job and a busy schedule”, and that online asynchronous classes in particular solve the problem that set course times conflict with work schedules.

Meeting Health and Mental Health Needs. The last key subtheme surrounding flexibility of online learning centered around accommodating students with healthcare challenges. For example, one student noted that their epilepsy makes it impossible to drive, and another noted needing online classes while recovering from a major surgery. It was also noted that asynchronous learning is beneficial for scheduling medical appointments like physical therapy. Even for those who already received accommodations through campus disability services, online classes were preferred, with one student explaining “I have a chronic disability… and asynchronous classes (when available) are helpful in managing attacks.” Mental health needs also emerged, such as one student who said, “I have ADHD and suffer from migraines which limit my ability to be present consistently, so online coursework generally provides flexibility and the ability to work ahead”. Online learning makes it possible for those with health limitations to still pursue their education: “I have many medical concerns that would prohibit me from going to the school for my courses.”

Self-Starters

While much of the discussion around online learning centers on how these flexible arrangements can help students overcome barriers to learning, a more strengths-oriented theme emerged in this study. Rather than being a useful alternative to accommodate busy schedules, many students conceptualized online learning as a preferred method that better aligns with their skill sets. For instance, one learner reported, “I am self-motivated and can thrive even without face-to-face structured courses”. Students reported that remote learning allowed them to work at a faster pace, improve concentration and focus, and be more efficient. Key traits that came up included being a self-starter, having effective time management skills, and being organized and disciplined. Respondents also reported satisfaction in being more independent and accountable for their learning. To sum up this strengths-perspective, one student answered that they chose online courses not as a less desirable but more doable alternative to face-to-face classes, but simply because “I am a strong, highly motivated student who doesn't have trouble managing a lot at once.”

There’s No Place Like Home

Students who pursue fully remote degree programs can complete coursework from any number of locations, such as a library or coffee shop. Respondents of this survey overwhelmingly preferred learning at home specifically, rather than the idea that they could learn anywhere. Students reported preferring learning from the comfort of home for several reasons, including “I have less anxiety when in my space, I will perform better on my work when I am less anxious.” Students said they benefited from having control over their environment, being able to focus better, and being more comfortable. One respondent summed it up this way: “My office space at home is my sanctuary and I can make any adjustments I need to in order to reduce distractions”.

Challenges for Students and Content for Support Interventions

Time

In analyzing responses to the question, “What are the top three challenges or concerns with online learning?” The first theme that emerged was related to time. Students were worried about managing their time effectively and wisely. Many students reported concerns about completing assignments in a timely manner or forgetting about deadlines and/or missing due dates. As one student stated, “I do get nervous about missing a deadline for a submission, so I have been trying to stay ahead of schedule.” Many students also experienced challenges with scheduling. This included schedule conflicts with both personal commitments and work responsibilities. Many students reported being at their maximum capacity and shared concerns about being able to manage it all. Others reported difficulty with aligning due dates with work hours. As one student revealed “Time is my first challenge. As a wife, mother and high school teacher, my plate is already very full so I may have to work on school after business hours.”

Staying Motivated

Students reported challenges related to staying motivated. Several respondents attributed this to boredom or a lack of interest in their coursework, while others mentioned difficulty with holding themselves accountable without the additional layer of motivation that in-person courses offer. The freedom that online studies offered provided some students too much flexibility, which made them uncomfortable. As one student reflected “Online learning can be too flexible, meaning not enough structure due to it being essentially self-paced”.

Students also reported a lack of ability to remain focused due to a variety of reasons. As one student described, “Ultimately with how life generally works I can easily get distracted or bombarded by what is happening around me and can lose track on what I am supposed to be doing.” Family members, pets, and other home interruptions kept them from being able to focus on the task at hand. Not having a quiet place to work or relying on mobile workspaces also add to the lack of concentration. Screen fatigue as well as other health barriers such as fatigue and exhaustion, mental health conditions, and self-doubt affected students. As one student described “Will my depression cause my motivation to deteriorate?”

Far Away

Another theme that online students reported as challenging was a sense of being far away and what they may be missing out on. Some students were worried about feeling distant or isolated.

Support Programs. Students were concerned about not having the support that being on-campus would provide for them, including programs that the university provides like tutoring, organizations and campus events. As one student shared “I’m not part of the institution because I am not physically there.” Others described a lack of connection with peers, teachers, and professors. One student reflected: “I want to feel connected to my professors and classmates, so I'm worried about feeling distant.” This lack of social interaction and connection was seen as a barrier to being able to study and review together or have comradery and someone to bounce ideas off of. One student shared a lack of “spontaneous flow of ideas or exchanging ideas with peers” while another reported missing “face to face rapport”.

Connections with Faculty in Online Course Delivery. Faculty connections were also seen as a challenge. Being able to ask an immediate question, receiving timely communication and feedback from professors, and not being able to easily access faculty due to the distance were commonly reported from students. As several shared, “My biggest concern is not having questions answered in a timely manner.” Students reported learning better when they can listen to lectures and not having to focus on readings only to self-teach. As one described, “I still need a professor who lectures (even recorded). Otherwise, I feel like this is self-learning and that is not good.” Other students weighed in on an overabundance of reading materials, too much busy work, and how reading textbooks was not conducive to other learning styles. Hands on practice is missing in online environments. Some students were concerned that professors were not aware of the difference in online and in person learning and posted materials late or in an unorganized fashion. Others described too much content in too fast of a pace and a lack of clarity of expectations, instructions, or assignments.

Supports Services Desired

To support student success, it is critical for university faculty, staff, and administrative leadership to be aware of what resources students need. A total of 392 students provided responses for the question, “What supports or services would you like the university to provide to facilitate your online learning experience?”, listing between one and three support services desired. Table 2 illustrates key findings.

Table 2

Support Services Desired

| Support | Count | Percent | |

| None | 117 | 29.77% | |

| Unsure | 24 | 6.11% | |

| Online Tutoring | 76 | 19.34% | |

| IT Support | 57 | 14.50% | |

| Instructor Accessibility | 34 | 8.65% | |

| Academic Advisors | 30 | 7.63% | |

| Quality of Teaching | 26 | 6.62% | |

| Belonging | 17 | 4.33% | |

| Library | 16 | 4.07% | |

| Disability Services | 11 | 2.80% | |

| Mentoring/ Check In | 9 | 2.29% | |

| Wellness Resources | 8 | 2.04% | |

| Mental Health Supports | 4 | 1.02% | |

| Open Education Resources (OER) | 4 | 1.02% |

When asked the last question, “What supports or services would you like the university to provide to facilitate your online learning experience? “, the most common result was that students did not request any support services beyond what was already provided (29.77%). A further six percent of respondents indicated that they were currently unsure what services were needed, and that they would have a better grasp of recommended supports after some time in the program.

The second most frequent response type was noting the value of online tutoring. Of note, academic tutoring (19.34%) was a more prominent theme than IT support (14.50%). Specifically, writing and math support were by far the most frequent content areas mentioned for tutoring support. In order to support online students, the importance of having supplemental academic resources specifically for math and writing cannot be overstated.

Two prominent responses centered around instructional support (15.27%), with the first being instructor accessibility (8.65%). Within this theme, students noted the importance of professors being available and responsive with emails and student questions. Respondents highly valued instructor engagement, with one student hoping to have “highly invested professors who don’t “forget” about their online students.” Another student similarly wrote, “I want to feel like I am part of the journey and not left out.” The other subtheme related to instructional elements was quality teaching (6,62%), such as professors providing clear and specific directions, having recorded video lectures, sending due date reminders, and being flexible.

Discussion

Including open-ended questions in the ORSSA survey proved to be an instrumental strategy for uncovering student strengths, concerns, and needs in an organic, non-biased, and learner-centered manner. The participants included flexibility in online learning as a key advantage. This is not a new concept, as countless studies have highlighted the convenience and flexibility of studying online (Tarrayo et al., 2023; Cramarenco et al. 2023; Hass et al., 2023). New studies, however, call for universities to provide more online, flexible, and informal learning environments where students can learn and collaborate without travelling to campus (Valtonen et al., 2021). This flexibility also allowed them to cope with their mental health and mental health needs. There has been copious research identifying the negative mental effects of online learning including fears of isolation, academic failure, and losing social relationships (Al-Maroof et al., 2023), as well as reduced mental resilience among online students (Wang, 2023). Much of the recent research is focused on the negative mental health effects of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. One study, however, found that burnout, depression, anxiety, and somatic symptoms among medical students were lower once they changed to online learning during the pandemic (Bolatov et al., 2021). More research needs to be conducted on the mental health benefits of online learning, particularly on how it can reduce social anxiety, promote feelings of safety, and lower anxiety levels.

The participants in this study noted that time management was a key challenge to online learning. Poor time management has been positively correlated with anxiety among online students. If time management was poor, then students’ anxiety increases, whereas if time management was efficient, then student anxiety decreases (Hassan et al., 2021). Research has shown that if students are given proper time management training, they will have less anxiety in their personal, social, and academic lives (Zhang et al., 2020).

Motivation was also viewed as a barrier to success in these participants. There have been numerous studies that examined factors that motivate students in online learning environments, with many focusing on improving student skills and competencies for online success. Mendoza et al. (2023) described how needs-supportive teaching “…creates a learning environment that supports students' basic psychological needs for relatedness, competence, and autonomy” (p. 2). The study highlights how student achievement, motivation, engagement and well-being are promoted when faculty clearly explain the ‘why’ for learning tasks, set clear and actionable learning goals and allow for flexibility in learning strategies.

A yearning for connections among students and faculty were also among the forefront of the participants identified challenges. Students have identified the following factors that can lead to a lack of interest in coursework: lack of social interaction with other students and faculty, a mismatch between learning expectations and course content, and a poorly organized online environment (Esra & Sevilen, 2021). Designing a user-friendly learning environment, promoting digital competencies such as online self-efficacy and autonomy, creating social and collaborative environments for peer support, and enhancing faculty online learning delivery skills have all been identified as critical motivational factors for online students (Chiu et al. 2021). Several studies have noted that student-faculty connections can be even more important than student-student interactions at fostering engagement (Martin & Bollinger, 2018). “Effective online teachers support their students through timely, proactive, embedded support which establishes their personal presence and actively engages students through synchronous and asynchronous methods” (Farrell & Brunton, 2020, p.4). A study by Hollister et al. (2022) noted the importance of four ways that faculty can connect with students to promote online engagement: availability of open communication channels between students and faculty, timely and consistent feedback given to students, consistent communication of announcements, rubrics and expectations, and faculty adopting a minimal role in online discussion forums.

While most of the students did not identify the desired support services requested, many of the students were unsure of what they needed. A recent study by Kember et al. (2023) suggests four levels of support for online students that included support from central university services, online instructors, online peers, and families and workmates. This indicates that, in addition to offering a survey of student needs during program orientation, assessing needed support services after the first semester of courses could capture additional valuable data. A recent study notes that effectiveness of the support provision depends on when the support is offered. In addition, support at transitional periods during a student’s academic career and measurement of online support interventions remain under-researched (Rotar, 2022).

Around 19% of college students are estimated to have a disability (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2018) but only 3% of our population noted disability services and advocacy as a needed support for online learning. This finding may support the notion that many college students who could qualify for supportive services do not seek them out, as most do not inform their college of their disability (NCES, 2022). Further education and advocacy may help students with disabilities be aware of what benefits they are entitled to and encourage accessing needed resources.

In response to the continuously rising cost of earning a degree (Gardner, 2022), educators are increasingly embracing the use of open-education resources (OER)- course materials, which are licensed to be free to access, and sometimes modify (UNESCO, 2023). This trend is congruent with what Grise-Owens (n.d.) calls righteous rage- turning anger at an injustice into tangible solutions. Our study indicates that there is a small (n=4) but meaningful subset of students who are entering the university demanding OER from the outset.

The Voice of the Online Student (VOS) Framework

Based on the student responses in the results section and the three topics in the discussion section, a preliminary framework comprised of five elements that emerged from the open-ended questions on the ORSSA survey is proposed. This framework is entirely based on the responses (and voices) of incoming online students at the University. The VOS Framework can be seen in Figure 2. A detailed description of each of the dimensions and elements with examples can be found in Table 3.

Figure 2

The Voice of the Online Student (VOS) Framework

Table 3

Dimensions, Elements and Examples of the VOS Framework

| Dimension | Elements | Examples |

| Student Organization | Time Management |

|

| Personal Scheduling |

| |

| Student Sense of Belonging | Connections with other Students |

|

| Connections with University |

| |

| Student Engagement | Build Motivation |

|

| Online Self-Efficacy |

| |

| Support Structure | Personalized and Proactive |

|

| Online Resources |

| |

| Academic Advising |

| |

| Tutoring or Mentoring |

| |

| Faculty Online Competencies | Teaching Presence |

|

| Online Delivery |

| |

| Connections with Students |

|

Limitations

It should be noted that all the qualitative data in this study was derived from the open-ended questions on the ORSSA survey. A more detailed examination of the incoming student experience could be achieved through interviews and focus groups. Also, the participants in this study were overwhelmingly female (86.7%) and were studying the healthcare disciplines of nursing (71.4%) or social work (20.2%). This was because they were the first two colleges to be included in the online orientation program. As online orientation scales across campus at the University, a more robust number of students diversified by gender and college will be included in the ORSSA open-ended responses.

Future Research

Recommended research for future studies includes the study of student demographics (such as college, nationality, gender, age, first generation college students) and their correlation to ORSSA responses, the inclusion of quantitative responses for a more generalized view of the ORSSA qualitative data, or to match the identified student supports with five phases of Rotar’s (2022) learning cycle. In addition, researchers could create and validate an evaluation tool for the VOS Framework and outcomes of student success programs.

Conclusion

This study proposes a framework for online student success and support programs (the VOS Framework) that is based on student responses to the open-ended questions on the Online Readiness and Student Success Assessment in the university’s online orientation program. This framework of themes (Organization, Engagement, Support Structure, Sense of Belonging, Faculty Competency) should be embedded in a comprehensive and holistic student success program that is proactive, customizable according to a student’s needs, and available at various stages in the online student’s journey. In addition, universities should develop evaluation mechanisms and tools to examine how the five themes improve an online student’s learning experiences and personal growth while at their institution. Further research is recommended to validate the elements of the framework and combine them in a mixed methods study with the newly validated ORSSA quantitative survey.

References

Adams, D., Chuah, K. M., Sumintono, B., & Mohamed, A. (2022). Students' readiness for e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in a South-East Asian university: a Rasch analysis. Asian Education and Development Studies, 11(2), 324-339.

Al-Maroof, R. S., Salloum, S. A., Hassanien, A. E., & Shaalan, K. (2023). Fear from COVID-19

and technology adoption: the impact of Google Meet during Coronavirus pandemic. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(3), 1293-1308.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1830121

Atkinson, J. K., Blankenship, R., & Bourassa, G. (2012). College student online learning readiness of students in China. China-USA Business Review, (3), 438-445.

Bolatov, A. K., Seisembekov, T. Z., Askarova, A. Z., Baikanova, R. K., Smailova, D. S., & Fabbro, E. (2021). Online-learning due to COVID-19 improved mental health among medical students. Medical science educator, 31(1), 183-192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-01165-y

Bryant, J., & Adkins, (2013). National research report: Online student readiness and satisfaction within subpopulations. Cedar Rapids, IA: Noel-Levitz, LLC.

Brindley, J. E. (2014). Learner support in online distance education: Essential and evolving. In O. Zawacki-Richter & A. Terry (Eds.), Online distance education. Towards a research agenda (pp. 287–310). AU Press.

Cheon, J., Cheng, J., & Cho, M.-H. (2021). Validation of the online learning readiness self-check survey. Distance Education, 42(4), 599–619. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2021.1986370

Chien, H., Yeh, Y.-C., & Kwok, O.-M. (2022). How online learning readiness can predict online learning emotional states and expected academic outcomes: testing a theoretically based mediation model. Online Learning, 26(4). https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v26i4.3483

Chiu, T. K., Lin, T. J., & Lonka, K. (2021). Motivating online learning: The challenges of COVID-19 and beyond. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 30(3), 187-190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00566-w

Chung, E., Noor, N. M., & Mathew, V. N. (2020). Are you ready? An assessment of online learning readiness among university students. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 9(1), 301-317. https://doi.org/10.24191/ajue.v16i2.10294

Clarke, V., Braun, V. & Hayfield, N. (2015). Thematic analysis. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (3rd ed, pp. 222-248). Sage.

Cramarenco, R. E., Burcă-Voicu, M. I., & Dabija, D. C. (2023). Student perceptions of online education and digital technologies during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Electronics, 12(2), 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12020319

Dello Stritto, M. E., Aguiar, N., & Andrews, C. (2023). From online learner readiness to life long learning skills: A validation of the learning skills journey tool. Online Learning, 27(4), 413-439. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v27i4.3880

Doe, R., Castillo, M. S., & Musyoka, M. M. (2017). Assessing online readiness of students. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 20(1), 1-13.

Esra, M. E. Ş. E., & Sevilen, Ç. (2021). Factors influencing EFL students’ motivation in online learning: A qualitative case study. Journal of Educational Technology and Online Learning, 4(1), 11-22.

Farrell, O., & Brunton, J. (2020). A balancing act: a window into online student engagement experiences. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 17(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/0.1186/s41239-020-00199-x

Firat, M., & Bozkurt, A. (2020). Variables affecting online learning readiness in an open and distance learning university. Educational Media International, 57(2), 112–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2020.1786772

Gardner, L. (2022). Why does college cost so much? The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/why-does-college-cost-so-much

Garrett, R., Suminich, B., Legon, R., & Frederickson, E. E. (2023, August 15). 2023 CHLOE 8 Report. Quality Matters. https://www.qualitymatters.org/qa-resources/resource-center/articles-resources/CHLOE-8-report-2023

Grise-Owens, E. (n.d.). Self-care A-Z: Rage, joy, justice, and self-care. The New Social Worker. https://www.socialworker.com/feature-articles/self-care/rage-joy-justice-self-care/

Hass, D., Hass, A., & Joseph, M. (2023). Emergency online learning & the digital divide: An exploratory study of the effects of covid-19 on minority students. Marketing Education Review, 33(1), 22-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/10528008.2022.2136498

Hassan, K., Zaheer, H., & Khalid, S. (2021). Relationship among online learning, time management and self anxiety of university students during COVID-19. Pakistan Journal of Distance and Online Learning, 7(2), 69-86.

Hollister, B., Nair, P., Hill-Lindsay, S., & Chukoskie, L. (2022, May). Engagement in online learning: student attitudes and behavior during COVID-19. Frontiers in Education 7, 851019. Frontiers Media SA.

Hung, M. L., Chou, C., Chen, C. H., & Own, Z. Y. (2010). Learner readiness for online learning: Scale development and student perceptions. Computers & Education, 55(3), 1080-1090.

Joosten, T., & Cusatis, R. (2020). Online learning readiness. American Journal of Distance Education, 34(3), 180–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2020.1726167

Karatas, K., & Arpacı, I. (2021). The role of self-directed learning, metacognition, and 21st century skills predicting the readiness for online learning. Contemporary Educational Technology, 13(3) https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/10786

Kember, D., Trimble, A., & Fan, S. (2023). An investigation of the forms of support needed to promote the retention and success of online students. American Journal of Distance Education, 37(3), 169-184. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2022.2061235

Kim, H., Sefcik, J. S., & Bradway, C. (2017). Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: A systematic review. Research in Nursing and Health, 40(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21768

Landrum, B. (2020). Examining students' confidence to learn online, self-regulation skills and perceptions of satisfaction and usefulness of online classes. Online Learning, 24(3), 128-146. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v24i3.2066

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage Publications.

Lockman, A. S, & R. Schirmer, B.R. (2020). Online Instruction in Higher Education: Promising, Research-based, and Evidence-based Practices. Journal of Education and E-Learning Research, 7(2), 130–152. https://doi.org/10.20448/journal.509.2020.72.130.152

Martin, F., & Bolliger, D. U. (2018). Engagement matters: Student perceptions on the importance of engagement strategies in the online learning environment. Online Learning, 22(1), 205–222. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v22i1.1092

Mendoza, N. B., Yan, Z., & King, R. B. (2023). Supporting students’ intrinsic motivation for online learning tasks: The effect of need-supportive task instructions on motivation, self-assessment, and task performance. Computers & Education, 193, 104663.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104663

Muljana, P. S., & Luo, T. (2019). Factors contributing to student retention in online learning and recommended strategies for improvement: A systematic literature review. Journal of Information Technology Education Research, 18, 19–57. https://doi.org/10.28945/4182

National Center for Education Statistics. (2018, May). Number and percentage distribution of students enrolled in postsecondary institutions, by level, disability status, and selected student characteristics: 2015–16 [Data table]. In Digest of education statistics. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d20/tables/dt20_311.10.asp

National Center for Education Statistics. (2022, April 26). A majority of college students with disabilities do not inform school. U.S. Department of Education. https://nces.ed.gov/whatsnew/press_releases/4_26_2022.asp

Nwagwu, W. E. (2020). E-learning readiness of universities in Nigeria-what are the opinions of the academic staff of Nigeria’s premier university? Education and Information Technologies, 25(2), 1343-1370.

Rotar, O. (2022). Online student support: A framework for embedding support interventions into the online learning cycle. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 17(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41039-021-00178-4

Sun, Y., & Rogers, R. (2020). Development and validation of the online learning self-efficacy scale (OLSS): A structural equation modeling approach. American Journal of Distance Education, 35(3), 184-199. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2020.1831357

Tarrayo, V. N., Paz, R. M. O., & Gepila Jr, E. C. (2023). The shift to flexible learning amidst the pandemic: the case of English language teachers in a Philippine state university. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 17(1), 130-143. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2021.1944163

UNESCO. (2023). Open education resources. https://www.unesco.org/en/open-educational-resources/statistics

Valtonen, T., Leppänen, U., Hyypiä, M., Kokko, A., Manninen, J., Vartiainen, H., ... & Hirsto, L. (2021). Learning environments preferred by university students: A shift toward informal and flexible learning environments. Learning Environments Research, 24, 371-388.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10984-020-09339-6

Warden, C. A., Yi-Shun, W., Stanworth, J. O., & Chen, J. F. (2022). Millennials’ technology readiness and self-efficacy in online classes. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 59(2), 226–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2020.1798269

Warner, D., Christie, G., & Choy, S. (1998). Readiness of VET clients for flexible delivery including on-line learning. Australian National Training Authority.

Wang Y. (2023). The research on the impact of distance learning on students' mental health. Education and Information Technologies, 1–13. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11693-w

Yu, T. (2018). Examining construct validity of the student online learning readiness (SOLR) instrument using confirmatory factor analysis. Online Learning, 22(4), 277- 288. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v22i4.1297

Zhang, F., Liu, J., An, M., & Gu, H. (2020). The effect of time management training on time management and anxiety among nursing undergraduates. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 26(9), 1073-1078. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1778751