Abstract

Online learning has steadily increased since well before the COVID-19 pandemic (Seaman et al., 2018), but research has yet to explore online students’ perceptions of online exam proctoring methods. The purpose of this exploratory study was to understand the perceptions of fully online students regarding types of proctoring at a large state university in the United States of America. Specifically, this study sought to understand online students’ a) perceptions of proctoring features, b) perceptions of proctoring types, and c) satisfaction with proctoring types and features. Closed- and open-ended survey responses provided insight into online students’ perceptions regarding proctoring features such as free to use, 24/7 access, accessible through a computer, and no scheduling needed. Descriptive statistics found that Online AI (automated proctoring) was their preferred type of proctoring, followed by Online Live, and In-Person and open-ended questions provided context for their experiences. In all, results elucidated proctoring features of importance, as well as misconceptions and concerns about proctoring types for online exams.

Keywords: online exam proctoring, online student perceptions, proctoring types/methods, exam invigilator

Introduction

As online learning continues to expand, post-secondary institutions engage in complex decision-making about how new technologies and modalities uphold their commitments to academic integrity. One such avenue to uphold academic integrity is through online exam proctoring, which enjoys wide use (Butler & Roediger, 2007). Much of the literature surrounding online exam proctoring focuses on cheating or the efficacy of the technology (Alessio et al., 2017; Karim, et al., 2014; King et al., 2009). However, few studies examine exclusively online students’ perceptions of proctoring types. This research gap is meaningful given that students are central party in the educational endeavor and are not always given the option to choose proctoring platforms that work best for them due to organizational constraints (Coglan, et al., 2021). As such, the purpose of the current study was to understand the perceptions of online students who are enrolled in a fully online degree program regarding three types of proctoring at a large state university: Online AI (automated proctoring), Online Live and In Person proctoring. We sought to understand online students’ perceptions of proctoring features, perceptions of proctoring types, and satisfaction with proctoring types and features.

Literature Review

Profile of the Online Student

Venable (2022b) argued that the notion of the “typical” online student is hard to identify, having been further complicated through the COVID-19 pandemic. In a recent report, almost 80% of surveyed online students were older than 24 years (Venable, 2022a). Many online undergraduate students are enrolled full-time in their coursework (Aslanian et al., 2022; Venable, 2022b). In addition to taking courses, surveyed students were employed part-time or full-time (13-74%) (Aslanian et al., 2022; Venable, 2022a) and were also married or partnered (15-63%) while caring for at least one child under the age of 18 at home (56-90%) (Aslanian et al., 2022; Venable, 2022b). As Venable (2022a) found, students frequently listed “balancing education with work, family, and household obligations” as their biggest concern about remote or online learning (p. 10). Students are also conscious of how higher education impacts their finances (Aslanian et al., 2022). Increasingly, online students no longer reflect the stereotypical assumption of a college student: 18-years old, recently graduated from high school, and unfettered by the responsibility of a family structure in which they care for children. Many online students are managing multiple professional and family priorities, all while working toward their degrees. These complex experiences place increasing importance on affordable programs that provide flexible options for a diverse population of students (Aslanian et al., 2022; Venable 2022b).

Academic Integrity and Proctoring

Academic integrity (also, academic honesty) is a core tenet of institutions of higher education and denotes “either the moral code or ethical policies of an academic institution” (Dyer et al., 2020, p. 2). Furthermore, an institution’s ability to demonstrate high expectations and comparable outcomes for academic achievement is tied to its continued accreditation (Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities, 2020). Deterring academic dishonesty then is an ongoing area of interest and an expanding area of study (Alessio et al., 2017; Dyer et al., 2020; King et al., 2009), particularly regarding proctoring of exams. Studies using self-report measures have found students are more willing to engage in academic dishonesty, like cheating on an exam, when the exam is not proctored (Dyer et al., 2020). Similarly, Duncan & Joyner (2021) found that 66% of surveyed students and Teaching Assistants (TAs) said they thought proctoring was an effective way to ensure academic integrity, that it added value to their degree (51%) and that more students would cheat on exams that were not proctored (70%).

Recent studies have found grade disparities between proctored and non-proctored exams in online courses that suggest proctoring acts as a deterrent to cheating behaviors (Akaaboune et al., 2022; Alessio et al., 2017; Karim, et al., 2014; Oeding et al., 2024). Akaaboune et al. (2022) concluded that their results provide assurance that “proctoring in online classes can be successfully used to ameliorate undesirable behavior and maintain academic integrity and rigor” (p. 129). Similarly, Alessio et al. (2017) concluded that academic dishonesty likely occurred in non-proctored sections as indicated by the fact that students in non-proctored sections were four times more likely to receive an A grade compared with their peers in proctored sections (Alessio et al., 2017). Oeding et al. (2024) concluded that online proctoring served to deter academic misconduct as they saw a statistically significant impact on student’s final grades depending on proctoring status. Additionally, in an exploratory experimental study, Karim et al. (2014) found that remote webcam monitoring of exams decreased cheating and did not interact with individual differences to predict test performance or reactions of test-takers. More research is needed to understand the impacts of proctoring, specifically online proctoring, the focus of the current study.

Online Proctoring

Although there are various types of online proctoring and many definitions, the current study aims to contribute to this knowledge base in two ways: a) by focusing exclusively on online students and b) by exploring online students’ perceptions of proctoring. These aims are necessary for several reasons. First, little research exists exclusively examining the perceptions of fully online students in online degree programs. Studies often use the term “students” broadly, without differentiating whether participants are on-campus or exclusively online students (Afacan et al., 2020; Alessio et al., 2017; Dyer et al., 2020; King et al., 2009; Watson & Sottile, 2010; Woldeab & Brothen, 2019, 2021). In contrast, the current study focuses exclusively on online students in fully online programs. Additionally, the current study examines the perceptions of online students taking courses designed as part of a fully online degree program, not students taking in-person courses that switched to emergency remote courses during the pandemic. Online students have consistently used online proctoring as part of their online courses pre- and post-pandemic, and may continue to use it in the future, making it crucial for scholars, instructors, and administrators to understand their perceptions of proctoring methods.

Second, peer-reviewed scholarship in this area is vital considering that available information about student views of proctoring/monitoring (i.e., levels of satisfaction) are evaluated, analyzed, and disseminated almost exclusively through proctoring vendors. Vendors are not held to the same regulations (e.g., IRB vetting) and conventions for transparency (e.g., replicability of studies) in collecting, analyzing, and reporting data. For example, some vendors might only provide feedback options to students at the end of exams, which might miss valuable feedback from students who encountered technical issues that prevented them from completing their exam, foreclosing on an opportunity to provide feedback. As such, robust scholarly investigation of issues regarding online proctoring is crucial for understanding a broader range of student perceptions within the context of research regulations and conventions.

This understanding is especially salient given multiple critiques of proctoring. First, online students are engaging with these services amidst a cultural milieu that supports robust societal discussion about the value and necessity of proctoring in general and digital proctoring throughout the COVID-19 pandemic specifically (De Santis et al., 2020; Meulmeester et al., 2021). Although general media raise valuable questions about the utility of proctoring technologies, popular press pieces are often not informed by research, diminishing the value of such work for practitioners (Gallagher & Palmer, 2020; Lu & Darragh, 2021). Scholarly work has raised important questions about privacy and student autonomy (Coghlan, et al., 2021; Khalil, et al., 2021), particularly regarding automated proctoring. Additionally, automated proctoring technologies have received criticism regarding bias and discrimination inherent in the algorithms that direct the programs. This criticism stems from larger discussions of algorithmic bias in facial recognition software (Buolamwini, 2023), search engine results (Noble, 2018), and internet-based technologies more broadly (Benjamin, 2019). Additionally, students may encounter technical difficulties with proctoring services (De Santis et al., 2020; Langenfeld, 2020). Some scholars have criticized the entire notion of proctoring and argue it creates a high-stakes learning environment that undermines student learning (Duncan & Joyner, 2021; Rios & Liu, 2017); they suggest a variety of alternative assessment methods such as group projects, open-book exams, peer reviews and more (Hodges, et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2022). A full discussion of these issues is outside the scope of the current study, but we must acknowledge these concerns are top-of-mind for many students. High quality research is needed to assess and transparently report on student perceptions of these services to address these and other concerns.

Study Purpose

Online proctoring has been used for many years by institutions offering online courses; however, there has been very little literature available that showcases fully online students’ perceptions of online proctoring. Many factors ranging from course design to proctoring types could impact students’ experiences; however, the available literature does not indicate how these factors could influence student perceptions of online proctoring.

As such, the purpose of the current study was to understand fully online students’ perceptions of proctoring at a large state university in the United States. Specifically, this study sought to understand online students’:

- Perceptions of proctoring features

- Perceptions of proctoring types

- Satisfaction with proctoring types and features

Methods

More than 3,800 fully online students who took courses during Fall and Winter terms (September 2021 – March 2022) at a large public university in the western United States were contacted to participate in this study (see appendix A). They were potentially located in any of the 50 states in the United States or 49 other countries. Of the 245 individuals who responded, 59% identified as female, 32% as male, 2% as non-binary or other and 7% chose not to identify. Reported age ranged from 18-89, with 53% between 25 and 34. While all participants were considered fully online at the time of the study, 78% had taken at least one in-person, on-campus course at some point during their postsecondary education. Respondents in this study experienced one or more of the below proctoring methods for online exams. The standard practice for each at the time respondents were surveyed are listed below:

- Online AI: Generally referred to as “automated proctoring or monitoring,” instructors using automated proctoring can input exam security settings and the level of importance for each to produce flags (a prompt to review). These exam settings can be adjusted before or after an exam, allowing the instructor to adjust flags based on what they determine important; the creation of flags is controlled by the instructor for each exam. Students download a web browser extension to take the exam using an automated proctoring technology. Exam session information (e.g., audio, screen share, video, or other information from the exam session) is collected when an exam is accessed using the web browser extension and is stored inside the institution’s Learning Management System (LMS). Only the instructor or university-determined LMS administrator can review exams using automated proctoring. The extension is limited to the web browser in which it was downloaded, and does not access information from various parts of the user’s computer. Since no live proctor is involved, students do not have to schedule their exam session or pay a proctoring fee.

- Online Live: Exam instructions are provided to a third-party vendor by the institution’s personnel so the vendor can administer proctored exams using their technology and proctors. Since a live proctor is involved, students schedule their exams and pay the vendor for exam sessions. Students log into the vendor’s online platform so a live proctor can administer the proctored exam. Exam session information (e.g., audio, screen share, video, or other information from the exam session) is also collected during Online Live proctoring. Online Live has two main differences from Online AI: a) first, a person in real time is on the other end of an online platform observing the test taker and b) the information gathered during the testing event is stored in the vendor’s platform.

- In person: Students locate, select, and pay a local proctor based on established acceptable proctor criteria. Students submit their proctor’s information to the institutions personnel who conduct a verification process to determine whether or not the proctor meets the acceptable proctor criteria. Once a proctor is approved, the student receives an email with next steps so they can coordinate their exam session directly with the proctor. The proctor also receives exam instructions from the institution’s personnel so they can appropriately administer each exam. Once completed, students travel to their approved proctor’s location and take the exam in the same physical location as the approved proctor.

The researchers acknowledge that any partnership with a third-party vendor causes some elements of the student experience to be outside of the control of the institution; however, this research project does not rely on a purely experimental design and student perceptions of the entire process were deemed valuable enough to proceed, recognizing some perceptions may not be due to the institution.

Survey data was collected using both closed and open-ended questions, generated for the specific institutional context in which the first author, in his role as proctoring manager, as well as interested members within the institution, wanted to better understand the perceptions of the students to inform their decision-making to best serve the needs of their students, faculty, and staff. Questions focused on student demographics, students’ online experiences (e.g., how many courses they had taken online), and students’ perceptions of Online AI Proctoring, Online Live Proctoring, and In-Person Proctoring. Survey questions used the following terminology to distinguish available choices for student respondents:

- Online AI: technology records your exam session, no people are involved

- Online Live: a live person monitors your exam session through the webcam and computer screen

- In-Person: you go to a physical location where an in-person proctor administers your exam

Procedures

Survey questions for this descriptive study were developed based on the first author’s experiences with students, with input from institutional leadership and the division’s research unit. IRB approval was received for the study (IRB-2021-1296). Students were emailed a link to participate in the study if a) they were enrolled in a fully online program at the participating institution, and b) were taking at least one online course that required proctored exams over a span of two terms. After the initial email invitation was distributed, a reminder email was sent a few weeks later.

The anonymous survey was open for data collection during the span of one term. Before survey participants could access the survey, a) student authentication was required through the university’s single sign-on, b) students gave informed consent, and c) identified whether they were considered an adult in the state in which they reside, or, if located outside of the US, in the country they reside. Participants could withdraw from the survey at any point. As this was an exploratory study, data collection ended at the end of the term.

To ensure ethical treatment of participants, the first author, who works as the proctoring manager for the division, was not involved in the recruitment of students, participants were notified that their survey responses were collected anonymously and survey links were emailed instead of embedded into online classes to ensure students understood that their participation would not impact their academic performance.

As this study was an exploratory study, we used simple descriptive statistics to analyze the data and establish a baseline for comparison of future work supported by thematic qualitative coding (Braun & Clarke, 2012) to gain insight into student perceptions. Descriptive studies hold much value for knowledge development. Corbin and Strauss (2015) argued that description is one of the main aims of research and that descriptive studies can provide insightful information about a phenomenon. Description is part of communicating about a phenomenon and is helpful in addressing emerging or under-developed areas of research (Corbin & Strauss, 2015), such as the perceptions of online students toward proctoring. Descriptive work lays the foundation for future abstraction and theorizing within a field and is an important step in the development of knowledge.

Results

The purpose of this exploratory study was to understand online students’ a) perceptions of proctoring features, b) perceptions of the proctoring types, and c) satisfaction with proctoring types and features. Closed- and open-ended survey responses provided insights into online students’ perceptions regarding the study’s focus areas.

Proctoring Features

The first focus area was online students’ preferences for various proctoring features on a three-point rating scale (not important, somewhat important, very important). Descriptive statistics found that the proctoring features students found “very important” were the following: free to use (85.9%), 24/7 access (83.8%), accessible through a computer (82.2%), and no scheduling needed (81.1%). Most students indicated they would like more than one proctoring option (41.7% = somewhat important and 37.4% = very important) and that having a live person monitoring the exam session (81.5%) was not important.

Table 1

Proctoring Features Rated by Importance

| Proctoring Features | Not important | Somewhat important | Very important |

| Free to use | 3.54% | 10.63% | 85.83% |

| No scheduling needed | 5.12% | 13.78% | 81.10% |

| 24/7 access to take exams | 3.15% | 12.99% | 83.86% |

| Access through a computer | 5.51% | 12.20% | 82.28% |

| More than one proctoring option available | 20.87% | 41.73% | 37.40% |

| Live person monitoring your exam session | 81.50% | 15.35% | 3.15% |

| *Other, please explain | 65.35% | 5.51% | 29.13% |

Qualitative responses contextualize the quantitative data. Some students submitted qualitative responses to indicate they would like other proctoring options (65.3%), such as not having proctored exams, having a member of their university proctor them, or offering alternatives for assessment. Other responses indicated cost was a feature that students considered when choosing proctoring options. One respondent explained their views on online live proctoring saying, “Scheduling and paying for [online live proctoring] upfront was awful. It was a great relief to switch to Online AI.” Another said of in-person proctoring, “Not only do [I] miss work but then there is the cost of having to pay for the [in-person] proctor, this can get very expensive multiple times per quarter especially if you have multiple courses that require proctoring.” These expenses, such as the cost of missing work or paying for multiple exams, could quickly make it untenable for students to engage with this proctoring type. Responses also aligned with the features of 24/7 access and accessing proctoring through a computer, one participant stating, “[In-person proctoring] was difficult option for some of us that work [fulltime].” This exemplar reveals the balancing act that many students must maintain between their employment and their schooling, another element students must consider when it comes to proctored exams. Together, these comments demonstrate that students make decisions about proctoring type (Online AI, Online Live, or In-Person) based on proctoring features (i.e., cost, scheduling etc.).

Proctoring Type

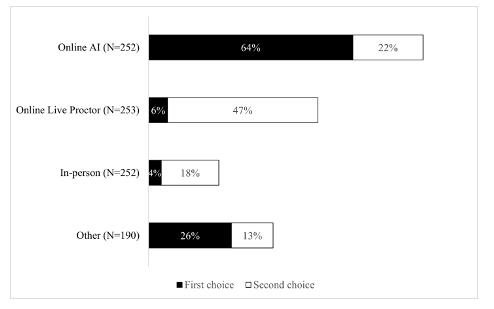

The second focus area asked online students to rank their preferred proctoring types for online courses that require proctored exams. Descriptive statistics found students ranked the following proctoring types as their first choice: Online AI (64%), Online Live (6%), In-Person (4%), and Other (28%). The following proctoring types were ranked as their second choice: Online Live (47%), Online AI (22%), In-Person (18%), and Other (13%). The majority of responses for “Other” indicated students preferred non-proctored exams.

Figure 1

Students’ Preferred Proctoring Types

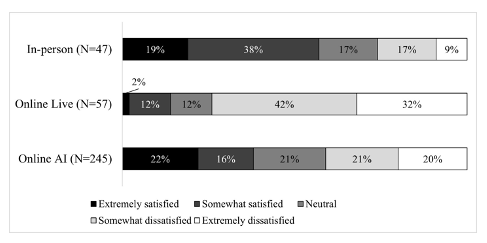

Satisfaction with Proctoring Types and Features

The third focus area asked students about their satisfaction with each proctoring type. Students ranked their level of satisfaction with each type (Online AI/ Online Live/ In-Person). Students who used Online AI (N=245) indicated their satisfaction with this proctoring type were as follows: extremely satisfied (22%), somewhat satisfied (16%), neutral (21%), extremely dissatisfied (21%), and somewhat dissatisfied (20%). Students that had used Online Live proctoring (n=57) indicated satisfaction levels of extremely satisfied (2%), somewhat satisfied (12%), neutral (12%), extremely dissatisfied (42%), and somewhat dissatisfied (32%). Students who used In-Person proctoring (n=47) indicated satisfaction levels of extremely satisfied (19%), somewhat satisfied (38%), neutral (17%), somewhat dissatisfied (17%), and extremely dissatisfied (9%).

Figure 2

Satisfaction with Proctoring Types

Thematic analysis revealed satisfaction with certain proctoring features such as cost, convenience, and comfort. One student mentioned how cost-effective and convenient AI proctoring was for them, stating, “I like taking proctored exams using Online AI. It is much cheaper than getting an in-person proctor. It is also a great option for students that work full time and have difficulty schedul[ing] a proctor during the day.” This participant identified the feature of 24/7 access as meaningful to them. Similarly, students alluded to comfort, for example, one student contrasted Online AI proctoring with live proctoring, saying, “Someone actively watching was a little off-putting. It made me [self-conscious] and it was slightly harder to concentrate. The Online AI was a lot more comfortable for me.” These responses illustrated the perceived advantages of Online AI proctoring that students identified in their open-ended comments.

Respondents also expressed satisfaction with features of In-Person proctoring. One respondent commented, there were “[f]ewer distractions during the exam on site.” Another respondent stated, “I actually like the in-person. I didn’t mind being watched while I tested. I was able to work problems aloud with no interruption. It was the best experience for proctored tests.” These respondents identified their perceived advantages of in-person proctoring as fewer testing distractions and being able to work through problems aloud. Another respondent said,

I had a screen lockup on a test once and the live help assisted me in restarting the exam within minutes. It was very useful. I would prefer live proctoring to AI, given a choice, but I am comfortable either way.

These themes illustrated that some students prefer In-Person proctoring due to its physical environment meeting their individualized needs and preferences or due to the technical assistance they can use to problem solve when issues arise.

Discussion

This exploratory study examined online students’ a) perceptions of proctoring features, b) perceptions of the proctoring types, and c) satisfaction with proctoring types. Quantitative and qualitative responses painted a complex picture of students’ perceptions of proctoring types. First, survey responses revealed online students surveyed preferred Online AI (automated proctoring). Qualitative responses provided more nuance, mainly that students were concerned about data privacy/technological security, the accuracy of the technology, and technical issues while also identifying satisfaction with decreased cost and increased convenience. Next, quantitative responses revealed that Online Live proctoring was online students’ second choice. Qualitative responses indicated that online students were concerned about privacy, technology issues, and cost while also appreciating technical assistance from live proctors. And lastly, quantitative data indicated that students preferred In-Person proctoring the least, indicating concerns about the cost and limited availability for scheduling, while some respondents appreciated the distraction-free testing environment. Importantly, any type of proctoring that utilizes a student pay model could be prohibitive for some students. This study highlights the importance respondents placed on cost and flexibility which aligns with the complex lives these students lead (e.g., older than 24 years, working part- or full-time, caring for children, etc.).

Implications for Practice

This study elucidates misconceptions that students may hold about proctoring, as well as some understandable concerns. We will address the primary themes indicated and provide applied guidance for instructors, administrators, and practitioners.

Accuracy and Privacy

Results indicated that students surveyed had a mixed understanding of a) the process by which proctoring tools, particularly automated proctoring tools, flagged behavior that might qualify as a violation of academic integrity and, b) how such a flag might impact their grade. Importantly, students assumed that a wide variety of behaviors might prompt a flag and that those flags would automatically and negatively impact their grades. Clearly communicating grading policies and practices when any type of exam proctoring is used may alleviate several accuracy concerns. Respondents also indicated they were uncertain how online proctoring tools impacted a) their data privacy and b) the security of their devices, which aligns with previous work on student privacy and autonomy (Coghlan et al., 2021; Khalil et al., 2021; ul Haq et al., 2015). University personnel can work to educate students on these topics by transparently communicating what data is collected, who has access to that data, and how that data is used.

Affordability

The next practical implication of this paper is a highly impactful student concern: this study provides more evidence that students are sensitive to the costs associated with higher education. Indeed, Aslanian et al. (2022) found that students indicated their biggest challenge to completing their online program was “paying for higher education while minimizing student debt” (p. 10). Variable pricing models can make proctoring prohibitively expensive for some students. Administrators, instructors, testing professionals, or other personnel should consider multiple pricing options when evaluating proctoring options to ensure they are well-informed about the financial costs for both students and the institution.

Technology Issues and Internet Reliability

Some students identified concerns about experiencing an issue with their technology or internet reliability during an exam, as confirmed in previous literature (Johri & Hingle, 2021). Due to the high-stakes nature of an exam, students may experience heightened concern around encountering an issue that could end an exam before it is completed. Some technologies available for proctoring online exams can help reduce this concern by capturing and recording the reason an exam ended, (e.g., unstable internet, or navigating away from the exam webpage). Instructors can utilize this information to determine appropriate next steps for a resolution. This type of communication may also help to create a culture where students are confident in their instructors’ discernment and their own self-efficacy for resolving technical issues. It might also be beneficial to offer practice sessions, particularly with the online proctoring modalities to alleviate anxieties and troubleshoot technological issues ahead of time.

Flexibility

Flexibility emerged as another applied contribution, highlighting the various needs of an increasingly diverse student population. Online students are typically older (Venable, 2022a) with some work experiences (Aslanian et al., 2022), and usually managing family responsibilities (Aslanian et al., 2022; Venable, 2022b), employment (Venable, 2022a), and schoolwork (Aslanian et al., 2022; Venable, 2022b), making scheduling flexibility and multiple proctoring options for online exams much more important than for on-campus students. The flexibility allowed by types of proctoring that do not require a scheduled time was identified as important to many students in this study. In all, our results suggest that online students’ preferences are diverse, reflecting their distinct experiences, and institutions would do well to provide multiple types of proctoring options.

Limitations and Future Directions

One limitation of this study was the low survey response rate (7.4%, N=245). Second, this study was exploratory and, as such, results must be interpreted cautiously as there does not exist a robust set of previous literature upon which to contextualize these results. Third, in analyzing student responses, we discovered some students contrasted experiences at their current institution with those at previous institutions; future work should clearly prompt students to limit responses to the current institution. Fourth, the sample for this study was limited to one institution. Future work should strive for more robust response rates and responses from multiple institutions. We invite our colleagues to continue investigations of student proctoring preferences for several reasons. First, proctoring will remain in-demand as online learning continues to be a viable option for students. Second, students are active participants in their learning; professionals should expect continued student interest in the tools used throughout their education, proctoring or otherwise. And lastly, to date, the existing data on student perceptions does not identify the perceptions of online students in fully online degree programs. Also, what data does exist is often held by proctoring companies. Although this does not automatically diminish the quality of such data and interpretations, proctoring companies are not held to the same research standards as scholars, meaning scholars and institutional leaders should approach such data and interpretations with caution. It is incumbent upon scholars to build a robust literature in this area to provide high-quality, transparent research on student perspectives; such a reservoir of research would benefit scholars, institutions, students, proctoring administrators, and proctoring companies.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Afacan Adanır, G., İsmailova, R., Omuraliev, A., & Muhametjanova, G. (2020). Learners’ perceptions of online exams: A comparative study in Turkey and Kyrgyzstan. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 21(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v21i3.4679

Alessio, H. M., Malay, N. J., Maurer, K., Bailer, A. J., & Rubin, B. (2017). Examining the effect of proctoring on online test scores. Online Learning, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v21i1.885

Aslanian, C. B., Fischer, S., & Kitchell, R. (2022). Online college students report 2022. EducationDynamics. https://insights.educationdynamics.com/2022OnlineCollegeStudentsReport.html

Butler, A. C., & Roediger, H. L. (2007). Testing improves long-term retention in a simulated classroom setting. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 19(4–5), 514–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/09541440701326097

Coghlan, S., Miller, T., & Paterson, J. (2021). Good Proctor or “Big Brother”? Ethics of online exam supervision technologies. Philosophy & Technology, 34(4), 1581–1606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-021-00476-1

Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. L. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (Fourth edition). SAGE.

Benjamin, R. (2020). Race after technology: Abolitionist tools for the New Jim Code. Polity.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. (2018, January). Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 18:1-15. Retrieved from: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v81/buolamwini18a/buolamwini18a.pdf

De Santis, A., Bellini, C., Sannicandro, K., & Minerva, T. (2020). Students’ perception on e-proctoring system for online assessment. In EDEN Conference Proceedings (No. 1, pp. 161-168). Retrieved from: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=914574

Duncan, A., & Joyner, D. (2021). On the necessity (or lack thereof) of digital proctoring: Drawbacks, perceptions, and alternatives. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38(5), 1482–1496. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12700

Dyer, J. M., Pettyjohn, H. C., & Saladin, S. (2020). Academic dishonesty and testing: How student beliefs and test settings impact decisions to cheat. Journal of the National College Testing Association, 4(1). Retrieved from: https://www.ncta-testing.org/assets/docs/JNCTA/2020%20-%20JNCTA%20-%20Academic%20Dishonesty%20and%20Testing.pdf

Gallagher, S., & Palmer, J. (2020, September 29). The pandemic pushed universities online. The change was long overdue. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/09/the-pandemic-pushed-universities-online-the-change-was-long-overdue

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. EDUCAUSE Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

Johnson, N., Seaman, J., & Poulin, R. (2022). Defining different modes of learning: Resolving confusion and contention through consensus. Online Learning, 26(3). https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v26i3.3565

Johri, A., & Hingle, A. (2023). Students’ technological ambivalence toward online proctoring and the need for responsible use of educational technologies. Journal of Engineering Education, 112(1), 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20504

Karim, M. N., Kaminsky, S. E., & Behrend, T. S. (2014). Cheating, reactions, and performance in remotely proctored testing: An exploratory experimental study. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(4), 555–572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-014-9343-z

Khalil, M., Prinsloo, P., & Slade, S. (2022). In the nexus of integrity and surveillance: Proctoring (re)considered. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38(6), 1589–1602. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12713

King, C., Guyette, R., & Piotrowski, C. (2009). Online exams and cheating: An empirical analysis of business students’ views. The Journal of Educators Online, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.9743/JEO.2009.1.5

Langenfeld, T. (2020). Internet-based proctored assessment: Security and fairness issues. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 39(3), 24–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/emip.12359

Lu, C., & Darragh, E. (2021, November 5). Remote test proctoring apps are a form of mass surveillance. Teen Vogue. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/remote-proctoring-apps-tests

Meulmeester, F. L., Dubois, E. A., Krommenhoek-van Es, C. (Tineke), de Jong, P. G. M., & Langers, A. M. J. (2021). Medical students’ perspectives on online proctoring during remote digital progress rest. Medical Science Educator, 31(6), 1773–1777. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-021-01420-w

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. New York University Press.

Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities. (2020). NWCCU 2020 Standards. NWCCU. https://nwccu.org/accreditation/standards-policies/standards/

Oeding, J., Gunn, T., & Jones, A. (2024) The impact of remote online proctoring versus no proctoring: A study of graduate courses. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 27(1). https://ojdla.com/articles/the-impact-of-remote-online-proctoring-versus-no-proctoring-a-study-of-graduate-courses

Robert, J. (2022). Students and technology report: Rebalancing the student experience. EDUCAUSE. https://www.educause.edu/ecar/research-publications/2022/students-and-technology-report-rebalancing-the-student-experience/introduction-and-key-findings

Rios, J. A., & Liu, O. L. (2017). Online proctored versus unproctored low-stakes internet test administration: Is there differential test-taking behavior and performance? American Journal of Distance Education, 31(4), 226–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2017.1258628

Seaman, J. E., Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2018). Grade increase: Tracking distance education in the United States. Babson Survey Research Group.

ul Haq, A., Jamal, A., Butt, U., Majeed, A., Ozkaya, A. (2015). Understanding privacy concerns in online courses: A case study of proctortrack. In: Jahankhani, H., Carlile, A., Akhgar, B., Taal, A., Hessami, A., Hosseinian-Far, A. (eds) Global Security, Safety and Sustainability: Tomorrow's Challenges of Cyber Security. ICGS3 2015. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 534. Springer, Cham. https://doi-org.oregonstate.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/978-3-319-23276-8_12

Venable, M. A. (2022a). 2022 online education trends report. BestColleges.com. https://www.bestcolleges.com/research/annual-trends-in-online-education/

Venable, M. A. (2022b). 2022 trends in online student demographics. BestColleges.com. https://www.bestcolleges.com/research/online-student-demographics

Watson, G. R., & Sottile, J. (2010). Cheating in the digital age: Do students cheat more in online courses? Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 13(1). Retrieved from https://mds.marshall.edu/eft_faculty/1/

Woldeab, D., & Brothen, T. (2019). 21st century assessment: Online proctoring, test anxiety, and student performance. International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education, 34(1), 1–10. Retrieved from https://www.ijede.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/1106

Woldeab, D., & Brothen, T. (2021). Video surveillance of online exam proctoring: Exam anxiety and student performance. International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education, 36(1), 1–26. Retrieved from https://www.ijede.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/1204