Abstract

The increased demand for online courses correlates to increased workloads for faculty, staff, and leadership. Hiring, staffing, and other logistical matters often trump the emphasis on course quality. This paper introduces a strategic framework for creating and sustaining a successful distance education model. Tarrant County College Connect Campus is the provider of online courses and programs within a larger, urban, two-year public institution. Established as a campus in 2014, TCC Connect Campus reflects an intentional framework to ensure quality. Ten specific strategies for quality assurance in online delivery include: Online Instructor Certification, Peer Developed Courses, E-Faculty Coaching, Faculty Performance Indicators, Supplemental Evaluation Feedback Form, adoption of external standards, data dashboards, campus data team, faculty and leadership repositories, and course readiness checklist. These research-based tenets may be adapted and modified to address the needs of other distance education providers.

Keywords: Distance education, online learning, quality assurance, faculty performance, professional development

Distance education is not immune to the lingering effects of a global pandemic. Hastily planned remote instruction differs from fully planned and intentional online college programs (Wood, 2024). For institutions and educators, restoring the reputation and validity of distance education requires intentional effort. Emphasizing quality is paramount to building and sustaining an educational model that promotes retention, success, and satisfaction for all stakeholders.

While methods and processes vary among institutions and even campuses, there are research-based tenets applicable to all providers of distance education. Among the online learning trends, there are proven practices to ensure online course quality. This article highlights ten practices- presented as non-chronological steps- geared towards quality assurance.

Step 1: Online Instructor Certification

Planning is paramount in the online modality; training must be continuous (Irizzary Morales & Ocasio Casanova, 2020). Veteran faculty members may have the subject-matter expertise and pedagogical awareness needed to be successful in the physical environment, yet shifting to an online classroom requires unique professional development- delivered prior to and throughout the initial teaching assignment. Faculty wishing to teach online should first complete an Online Instructor Certification (OIC) course covering research-based instructional practices for online learning, campus/ district/ state/ regional/ federal requirements and including performance-based activities to simulate building a course within the learning management system. The OIC experience may encompass two LMS course shells: one where the faculty member learns as a student and is exposed to a model of exemplary design and delivery, another where the faculty member creates various course elements and integrates tools. OIC should be required prior to teaching online. This basic introduction ensures that faculty have the baseline for preparing a successful online class.

As distance education laws, guidelines, and policies evolve and change quickly, there is a need to provide timely and responsive professional development. An OIC model should include a recertification component. For example, at Tarrant County College Connect Campus, online instructors must complete a shorter, updated recertification course every two calendar years. This ensures timely updates are shared, modeled, and applied across the online campus. Beginning in 2022, regular and substantive interaction (RSI) and accessibility modules were added as recertification modules; this aligned and responded to recent changes in federal policy.

Step 2: Peer Developed Courses

Like the need to prepare faculty for teaching an online course, there is a need to design courses to be user-friendly. The purpose of Peer Developed Courses (PDCs) is to improve learning outcomes and student success. For students participating in multiple online classes- with multiple instructors- there is an opportunity to:

- standardize course layout

- simplify course navigation

- collaboratively develop courses with research-supported best practices in online learning

- create rich, engaging content and authentic assessments

Academic freedom is important to educators. A PDC does not limit an instructor's content or expression. Faculty are encouraged to add content to the PDC. However, it is good practice to streamline the design, allowing students to focus time and energy on learning content as opposed to learning how to navigate the online environment. Finally, the use of PDCs results in additional benefits to the institution. A PDC promotes low-cost scalability, incorporation of Open Educational Resources (OERs), and accessibility compliance.

Step 3: E-Faculty Coaching

Online campus administrators face a myriad of complex and unique challenges. One daunting challenge involves monitoring and providing timely feedback to instructors. An online campus typically has a lean structure; a small number of Deans and Department Chairs compared to a large, transient, adjunct faculty population. Faculty may teach in varying sessions and term lengths within the academic year, which compounds the challenge of completing formal reviews or performance evaluations on a regular schedule. E-Faculty coaches support faculty and review classes non-punitively, in between formal appraisal cycles. Instructors no longer wait or rely on a formal evaluation to receive feedback and tailored support. As a result, online courses are improved in real time.

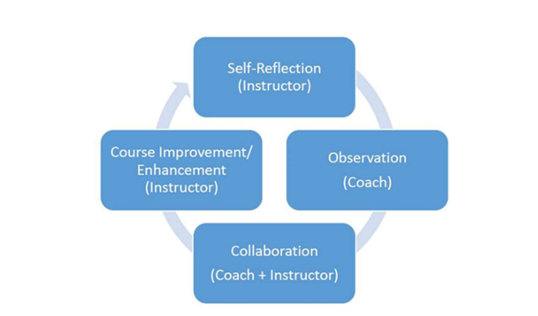

E-Faculty coaches view courses, collect data and work directly with instructors to identify strengths and areas for improvement based on standards for communication, interaction, support, and accessibility. Coaches serve as a "bridge" between instructors and campus leaders to support compliance and quality assurance measures in a non-evaluative, non-supervisory setting. Instructors actively communicate and collaborate with coaches; faculty drive the conversations based on their own needs. Consider the process flow illustrated in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Kelton & Morales (2022)

Step 4: Faculty Performance Indicators

Corporations commonly rely on Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) to relay expectations and align metrics. The Faculty Performance Indicators (FPIs) model communicates and focuses on ten essential elements of performance for faculty teaching in an online modality. Those ten elements include:

- Online Instructor Certification (OIC)

- End of Course (EOC) Evaluation Response Rates

- Student Success Rates

- Instructor Presence

- Instructor Interaction

- Course Communication

- Embedded Media

- Attendance

- Course Readiness

- Open Educational Resources (OERs)

Emphasis on these ten FPI- specific to online teaching- supports recent principles of good practice for distance education, per the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (THECB) Division of Digital Learning (2023). These indicators are measured according to the next step.

Step 5: Supplemental Evaluation Feedback Form

According to the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (2023), “an institution must have clear criteria for the evaluation of faculty teaching distance education courses and programs”. Many institutions have a formal evaluation process that is either limited to face-to-face modality or has minimal online-specific elements. Incorporating a supplemental set of criteria is critical to assessing the performance of online instructors. Once the Faculty Performance Indicators (FPI) are identified/ prioritized, a tool for aligned and meaningful assessment is created. This form can be integrated with the existing performance tool or used as a supplemental part of the process.

An excerpt from the supplemental evaluation feedback form (SEFF)- based on three FPI identified in Step 4- is shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

| Criteria / Element | Notes / Feedback | Score |

2.6 The instructor stated and followed a communication plan aligned with campus expectations (e.g., email response, response timeframe, grading and feedback timeframe, office hours, etc.) | 1=Yes 0 = Areas for improvement are noted | |

2.7 The instructor effectively used media (beyond the contents of a PDC) to enhance engagement and learning | 1=Yes 0 = Areas for improvement are noted | |

2.8 The instructor recorded student attendance aligned with campus expectations | 1=Yes 0 = Areas for improvement are noted |

Tarrant County College (2024)

Step 6: Adoption of External Standards

Online institutions should rely upon research-based, peer-reviewed external standards. One example of an external partner is Quality Matters. Quality Matters (QM) defines course alignment as the way that “critical course elements work together to ensure learners achieve the desired learning outcomes” (Quality Matters, 2024). The hallmark of the process is the QM Rubric: Higher Education General Standards, which consists of eight general standards:

- Course Overview and Introduction

- Learning Objectives (Competencies)

- Assessment and Measurement

- Instructional Materials

- Learning Activities and Learner Interaction

- Course Technology

- Learner Support

- Accessibility and Usability

(Quality Matters, 2024)

Allowing faculty the opportunity to obtain QM Rubric (APPQMR) certification is expensive; yet institutions may collaboratively seek membership as a consortium, and group trainings are another budget-friendly option. At a minimum, all instructional designers and academic leaders should be current on external, industry-based standards for excellence in distance education. The rubric provides a framework for aligning all other quality assurance efforts.

Step 7: Data Dashboards

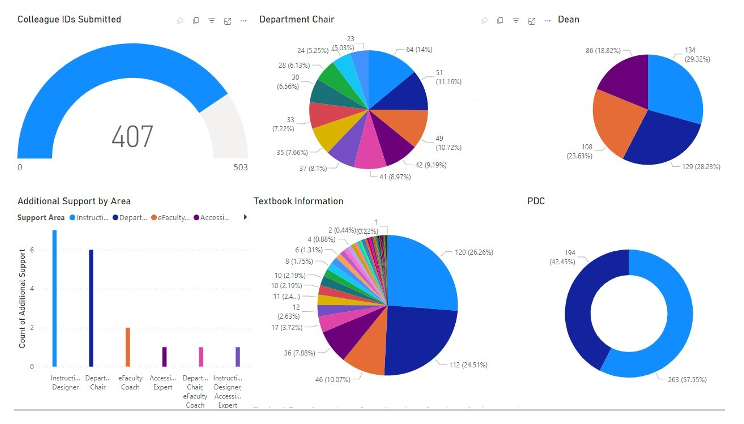

The use of data to inform decisions and processes is critical. Yet data is only effective when it is clearly communicated. Faculty and staff are easily overwhelmed by multiple data sources, sets, sites. Prioritizing data via dashboards is a solution. Data dashboards- generated by Microsoft, Smartsheets, or another platform- ensure simple access, visual representation, and comparison of real-time information. For example, an academic dean may facilitate a department-based dashboard reporting enrollment by program/ course, student success rates, retention rates, status of instructor OIC certifications, etc. Department chairs and other administrators would have instant access, limiting the need to request reports via email or meetings. Another powerful dashboard would allow faculty to see their own performance data over time. The sample data dashboard shown in Figure 3- generated via Power Bi- summarizes submissions and trends related to the Course Readiness Checklist described in Step 10 of this paper.

Figure 3.

Tarrant County College (2024)

Step 8: Data Team

Collecting, sharing, and analyzing data is the responsibility of all stakeholders; this is a culture shift for most institutions, where data typically is distributed from the top down. Forming a campus-based Data Team of faculty, staff, and leadership can produce powerful discussion and insight. Focus groups can target instructor outcomes, programs/ courses, student feedback, etc. This structure can lead to “aha” moments at multiple levels. For example, comparing student success rates between different term sessions, such as 16-week vs 8-week sessions, may yield more useful data than simply looking at general student success rates per course.

Step 9: Faculty and Leadership Repositories

Actively communicating and providing resources to faculty, department chairs, and deans in a remote environment requires substantial organization and planning. Creating repositories within the learning management system is a streamlined and efficient way to promote consistency. A digital faculty guide and/ or department chair repository allows instant access to documents, forms, support systems, data, etc. As an added benefit, housing information within the LMS encourages modeling of best practices for course design and navigation; faculty see an online “course” with accessible and engaging content.

Step 10: Course Readiness Checklist

Effective practices for ensuring online courses are student-ready may include the submission of a course readiness checklist. The course readiness checklist, submitted prior to the official class start date, asks faculty to verify/ acknowledge items are complete and current. Examples- aligned to the campus Faculty Guide and QM Rubric- may include:

- “I timely posted my Syllabus and Curriculum Vitae.”

- “I provided a link to the end of course evaluation.”

- “I posted the district policy on Artificial Intelligence (AI).”

- “I activated the attendance software.”

- “I included a Start Here button on the Home Page.”

For each item, a resource link is provided. This ensures faculty know where to go, or who to contact, if an item is unclear. It is also recommended to provide an automation feature wherein the faculty member may request an appointment with a department chair, instructional design team member, E-Faculty coach, or other support role.

Summary

The increased demand for online courses correlates to increased workloads for faculty, staff, and leadership. Hiring, staffing, and other logistical matters often trump the emphasis on course quality. Yet to remain relevant, innovative, and sustainable, institutions must be intentional and strategic in their quality assurance efforts. While immediately implementing all ten of the steps described in this article may not be feasible, each step is valuable in its own merit. To borrow and apply a phrase from a different context, “That’s one small step towards quality assurance, one giant step for campus culture” (Armstrong, 1969).

References

Armstrong, Neil. (1969). Translated. The History of Neil Armstrong's One Small Step for Man Quote | TIME

Kelton, K. & Morales, C. (2022). Coaching for Connection: A playbook for successful implementation of E Faculty Coaching. Presentation at Online Learning Consortium (OLC) Spring Conference, Dallas, April 2022.

Morales Irizarry, C. R., & Casanova Ocasio, A. J. (2020). Estrategias de apoyo a la facultad en tiempos de pandemia: La respuesta de dos instituciones. HETS Online Journal. XI(2), 60-78. Retrieved from https://hets.org/ejournal/2020/11/16/estrategias-de-apoyo-a-la-facultad-en-tiempos-de-pandemia-la-respuesta-de-dos-instituciones/

Quality Matters. (2024). Quality Matters

Tarrant County College. (2024). Supplemental Evaluation Feedback Form (SEFF).

Tarrant County College. (2024). Course Readiness Checklist Dashboard.

Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (THECB). (2023). Principles of Good Practice for Distance Education (texas.gov)

Wood, Sarah. (2024). 11 Online Learning Trends to Know Now. U.S. News Education. https://www.usnews.com/higher-education/online-education/articles/discover-current-online-learning-trends

-

Dr. Kristen Kirkpatrick is the Director of Academic Affairs, Operations at Tarrant County College, Connect Campus, Fort Worth, Texas. Email: kristen.kirkpatrick-130@tccd.edu

Dr. Carlos Morales is the President of Tarrant County College, Connect Campus, Fort Worth, Texas. Email: carlos.morales@tccd.edu

*This paper was one of three selected as a "Best Paper" among DLA 2024 proceedings, Jekyll Island, Georgia, July 28-31, 2024.