Abstract

The adoption of distance learning tools (DTLs) is an important factor for higher education faculty when making decisions regarding teaching online. The higher the self-efficacy levels in the use of the tools, the more likely faculty are to continue to teach online. Professional development in the use of DTLs increases self-efficacy. This study examines where faculty seek professional development and the levels of confidence through self-efficacy and Levels of Use from the Concerns Based Model for change in the use of the technology. Both of these factors are important as institutions determine the best value for their training dollars.

Keywords: concerns-based adoption model, distance learning, distance learning tools, higher education, professional development, and self-efficacy

Need for Professional Development for Distance Learning Tools

Many higher education faculty members have struggled to find the time required to learn the technology to teach online (Allen & Penuel, 2015). However, the sudden shift from predominantly in-person instruction to online course delivery methods prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic forced faculty to use distance learning tools (DLTs) with very little advance time to learn their implementation. Although the future of the pandemic's long-term impact on course delivery methods is unclear, society continues to view online instruction as a solution for other emergency situations, such as natural disasters or armed conflicts. Therefore, it is of monumental importance to understand what forms of professional development can foster faculty confidence and dispositions toward adopting and using DLTs.

The adoption of DLTs is an important first step toward faculty willingness to teach online. A subset of higher education faculty uses a plethora of DLTs. Typically, faculty struggle to find the time required to learn the technology to teach online (Allen & Penuel, 2015). Research on factors influencing faculty adoption of DLTs has indicated that faculty members' technology self-efficacy plays an important role in this process (Sangkawetai et al., 2020). Further, professional development and support contribute to increasing faculty confidence when adopting technology (Kebritchi et al., 2017). However, faculty continue to express a lack of confidence in using online technology even after receiving training (Kerrick et al., 2015). A potential factor contributing to the continual lack of confidence appears to be the absence of ongoing support after training (Osika et al., 2009).

As institutions evaluate the return on investment for distance learning programs, how to implement professional development to obtain the greatest impact for the dollars spent is an important consideration. Institutions implement a variety of models to provide professional development for online learning and the tools used to present information, formulate assignments, engage students, and provide formative feedback. Included within these models is professional development on how to use technology tools or pedagogy in teaching online with tools. Distribution of training can include outside resources such as webinars, conferences, or prepaid training modules. Internal resources include technology experts or online experts at the institution.

The goal of this study is to understand which professional development (PD) opportunities contribute to faculty attitudes and self-efficacy when adopting DLTs in their online courses and determine the approaches that achieve the best results. To achieve this goal, the researchers posed the following research questions.

- What types of professional development will faculty participate in to learn about DLTs?

- Will online faculty members express high levels of self-efficacy in the use of DLTs?

- Will online faculty members report higher levels of adoption of DLTs?

The results of this study can help higher education leaders and policymakers to better understand faculty PD practices as they relate to the adoption of DLTs.

Literature Review

Self-efficacy relates to a person's future-oriented belief in their ability to successfully learn and implement behaviors and practices (Bandura, 1977). Self-efficacy is context-specific regarding a person's belief in their abilities to handle distinct tasks and situations. Therefore, teacher self-efficacy includes the teachers' belief that they can bring about desired outcomes of student engagement and learning even when students are difficult or unmotivated (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 1998). A further specificity arises in teaching online, as this includes not only pedagogical approaches and didactical concepts but also a technological component. A specific expression of self-efficacy is, therefore, instructors' beliefs in their ability to perform actions necessary to conduct online teaching (Pajares & Schunk, 2002).

High levels of online teaching self-efficacy have been associated with extensive experience in teaching online (Robertson & Abdulrahman, 2012). Teaching the first course poses an essential hurdle, with self-efficacy peaking and leveling with the third course conducted online. Another factor contributing to the development of instructors' online teaching self-efficacy includes their interest in teaching online (Horvitz et al., 2015). Instructors' technological competence and their openness toward online teaching have also shown interactions with their self-efficacy (Petko et al., 2015). Instructors demonstrate more persistence when dealing with challenges, maintain a high motivation to use digital technologies, and provide creative access pathways to student learning (Van Acker et al., 2013; Zee & Koomen, 2016; Ma et al., 2021). Researchers have determined self-efficacy in online teaching creates positive interactions with instructors' technological-pedagogical content knowledge, as well as their use of constructive and interactive teaching activities (Sailer et al., 2021; Harris et al., 2017; Capone & Lepore, 2021; Ma et al., 2021).

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and the immediate transition to online teaching, instructors' self-efficacy beliefs gained unprecedented relevance. Since most instructors had no prior experience in conducting online teaching, they were unprepared for the didactical and technological challenges (Mitchell et al., 2015; Prottas et al., 2016; Olden et al., 2021). Alongside aid in setting up technological infrastructures, institutional support was necessary to foster instructors' self-efficacy (Creely et al., 2021). Such support through professional development is an important component for success in developing and designing suitable online classes for all learners (Kebritchi et al., 2017; Xu & Jaggars, 2013). An effective approach encompasses pedagogical approaches as well as instructional technology (Sendall et al., 2010). Higher participation rates in professional development on online teaching have been associated with increased self-efficacy (Dunbar & Melton, 2018). However, before the pandemic, little systematic support for designing online teaching was available (Archambault et al., 2016), and merely 30-40% of college and university instructors participated in professional development on online teaching (King, 2017). Without professional development, faculty members are significantly hindered in the successful implementation of online (Porter & Graham, 2016; Olden et al., 2021).

In-House or Beyond the Institution Learning Opportunities

Providing high-quality professional development is important to a higher education institution. Good professional development promotes higher job satisfaction and positive attitudes among faculty in the use of instructional technology (Song et al., 2018). Because professional development within an institution needs to be cost-effective, training opportunities should allow for tailored content specifically to the institution's needs. Many institutions have training teams. However, most institutions struggle with adequate funding for professional development initiatives (Eynon et al., 2023). When professional development is not available at the institution, faculty often look for professional development in other places (Eynon et al., 2023).

Often not discussed in the literature is that the scope of professional development offered by a central office of teaching and learning is broad to reach the widest group of faculty members. This is economically viable; however, faculty often express the wish for opportunities that are closely related to their content area expertise. This leads them to seek professional development beyond the university. Today, faculty have many options through their professional organizations and product training in a variety of formats. This poses interesting questions for a centralized professional learning center about where to invest money: in-house training or subsidizing the opportunities for professional development beyond the university.

Concerns-Based Adoption Model

The Concern- Based Adoption Model is a model developed by Hall and Hord (2014) based upon more than 20 years of research around the natural processes that occur within an organization as the culture adapts to changes driven by innovations both in new types of technological tools and processes that impact workflow. Hall and Hord have studied these changes both in educational and corporate settings (Hall & Hord, 2014). From their observations, they have created and tested tools to measure the progress of the adoption of the changes within the organization as they occur.

One of the tools used by Hall and Hord (2014) to assess where employees are within the adoption process is the Stages of Concern. The Stages of Concern are based upon the premise that individuals tend to move through stages as they adopt the innovation into their workflow. Not all individuals will fully embrace the identified innovation at the highest level. Knowing where the individuals in the organization are within those stages can assist professional development specialists in developing interventions to encourage higher levels of adoption.

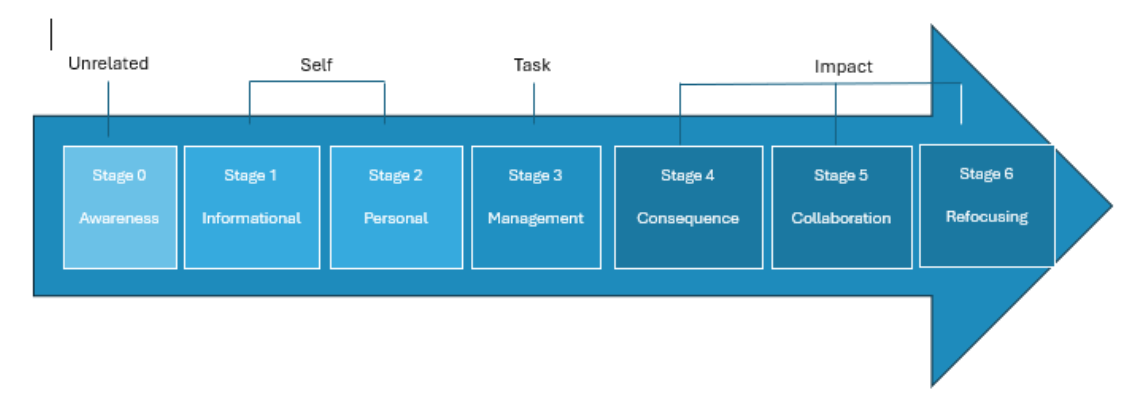

The Stages of Concern (SoC) framework consists of 7 levels coded 0 to 6 (Hall & Hord, 2014) divided into four categories based on how the concern relates to the workflow. The lowest category at level 0, Awareness, connects to the belief that the innovation is unrelated to the individual's workflow. As an individual learns about the innovation and how to use it, they pass through a self-related category that addresses the individual's concern for how the innovation will impact them personally. Of the two levels in this category, the first is Informational (1), which describes the individuals becoming interested in the general characteristics, effects, and requirements. Progressing to the Personal (2) level, the individual is unsure about their ability to use the innovation and evaluates the value of learning how to use the innovation within the organization's reward structure and the implications of the innovation. The third category is Task with one level called Management (3). The individual becomes focused on how to use the innovation and how the new process or tool impacts their efficiency, organizing, managing, scheduling, and time demands. The last category is Impact, which indicates a move away from self-related concerns toward the results of the use of the innovation. The lowest of the levels in this category is Consequences (4). The individual focuses on the immediate sphere of influence, how the innovation impacts the students or clients, and evaluates the impact. With a positive impact, the individual moves to the next level Collaboration (5) and begins to work with others to improve upon the use of the innovation. The highest level is Refocusing (6). At this point, the individual is exploring the broad implications and begins proposing alternatives in the current existing form of the innovation. Image 1 is a visual representation of the levels and the categories within the framework.

Image 1

Stages of Concern Continuum

Research Hypotheses

Starting from the assumptions of the Concerns-Based Adoption framework, the study investigated three hypotheses as follows:

- H0 1. Faculty are more likely to use the professional development offered by the distance learning office.

- H0 2: Online faculty will score at the higher impact stages of the CBAQ levels of concern.

- H0 3: The online faculty will express high levels of technical self-efficacy in the use of DLTs in online teaching.

Methodology

This quantitative study used survey techniques to measure self-reported data by faculty in their concerns about the use of distance learning, their levels of self-efficacy, the type of professional development they used, and the types of DLTs they are most likely to use. The survey tool consisted of four sections.

The first section of the tool included demographic data about the overall teaching experience, online teaching experience, professional rank, and college. The second section contained the modified questions from the concerns-based adoption questionnaire (CBAQ) (George et al., 2013). This section of the survey was validated through multiple studies (George et al., 2013). The CBAQ is a series of questions designed to determine the participants' levels of adoption along a continuum. The lower levels of the continuum indicate faculty seeking information about the new strategy or tool. Those in the middle of the continuum were working through the impact of the new strategy or tool on their workflow. Those at the top end of the adoption continuum were using the strategy or tool in creative ways and were willing to share what they had learned. The third section was the self-efficacy scale based on The General Self-Efficacy Scale created by Schwarzer and Jerusalem in 1995. That version was selected for this study because the questions closely aligned with the adoption of technology tools. The wording within the scale was modified to reflect DLTs. This way, the researchers could maintain the integrity of the scale while measuring the use of DLTs. The scale was reduced from 10 questions to 6 to reduce redundancy in the questions due to the length of the survey. The fourth section of the survey gathered information about the types of professional development the participants used from the different university resources.

Participants

The participants in this study taught online classes during the spring semester at a large regional institution in the Southeastern United States. The institution began as a commuter university but eventually expanded to undergraduate, master's, and doctorate degrees for 30,000 students. Approximately 30% of the courses offered were online. Each semester, 6,000 students enroll in online-only courses. The disruption of instructional delivery caused by stay-at-home directives launched a university-wide migration toward distance learning. Therefore, the respondents were those who were willing to share their online experiences and did so within days of the launch of the survey which was the week before the university closed for the pandemic. Therefore, these faculty were eager to share their positive or negative experiences in teaching online. The response rate for those first two days of the survey was 16%, with 42 of the respondents starting the survey and 34 completing it.

The sample was comprised of 42 teaching professionals who had attended professional development. Their teaching experience varied between 1 to 22 years (M = 12.8, SD = 6.3). Their online teaching experience, on the other hand, varied between 1 to 22 years (M = 8.0, SD = 5.0).

Institutional Context

The participants had access to multiple types of professional development to support online class development and teaching through two different offices. The instructional technology office provided training in the use of technology software and applications offered by the institution on a regular basis. The training department offered face-to-face and virtual training. When necessary, training staff conducted one-on-one assistance for faculty. Additionally, the university paid for 24/7 learning management system support.

The second office providing professional development was the office that managed the distance learning programs at the university. That office focused on the pedagogy aspect of the distance education tools available. The instructional design team offered a general training course in facilitating online instruction and another course in designing online courses. The design team also provided instructional designer support for course development, a professional learning community, an open lab for support in course development, and just-in-time resources on YouTube.

The types of DLTs available from the institution included several tools integrated into the learning management system, Canvas. Within Canvas, faculty had access to Speed Grader, which allowed them to grade assignments online. The tool includes a rubric, annotation tool, highlight tool, and very basic editing tools. Faculty could also use several of the popular web-conferencing tools to conduct office hours and teach synchronous classes. For prerecording lectures, various applications were available, including screencasting and voiceover. For more complex projects, the faculty had access to a video-recording studio with green screen capabilities. Grading and discussion board tools also were built into the learning management system. Table 1 indicates the distribution of the types of tools used by the faculty.

Table 1

Used by Faculty

| Distance Learning Tool | M |

| Speed grader | 5.5 |

| Discussion board | 5.7 |

| Web-conferencing | 3.6 |

| Google applications | 2.7 |

| Video recording (screen recording or voiceover) | 4.8 |

| Video recording in a studio | 4.2 |

Results

Professional Development

Research supports the belief that professional development is important in teaching faculty how to use technology. Access to professional development was identified as an important contributor to the adoption of technology by faculty. The office of distance learning was the group offering the training most closely related to online teaching specifically. Distance learning tool training is also offered by other offices on the campus. The instructional technology group is an example that offers training in how to use a distance learning tool. Because of the various offices offering a variety of options the following hypothesis was developed:

H0 1. Faculty would be more likely to use the professional development offered by the distance learning office.

The number of hours study participants (N = 42) had invested in their professional development varied greatly, with an M of 54.4 hours (SD = 43.2, see Table 2). While several participants reported over 220 hours invested in professional development, others had not engaged in professional development activities. The participants accessing professional development opportunities offered by the distance learning office (M = 14.2, SD = 12.1) and self-study (M = 14.9, SD = 13.1) options were most frequently used by the faculty. Courses offered by the instructional technology office were slightly less utilized by faculty than those offered through the distance learning office (M = 7.6, SD = 10.1). Of interest within this self-reported data was that the average across all professional development opportunities offered by the university (M = 25.6) was lower compared with training outside the university (M = 30.3). This group of participants spent, on average, M = 54.4 hours in professional development, reflecting the value these faculty members placed on professional development about online teaching. The data does not support H0 1, as faculty were not more likely to use university professional development over other non-instructionally driven opportunities.

Table 2

Number of Hours of Professional Development by Faculty Within the Past 5 Years by Type

| Professional Development | M |

| Distance learning office | 14.2 |

| Technology office | 7.6 |

| Other training at the university | 3.8 |

| Training outside of the university | 5.9 |

| Self-study (webinars and tutorials) | 149 |

| College courses | 12.8 |

| Other | 9.5 |

Levels of Adoption in Use of Distance Learning Tools

The section of the questionnaire with the CBAQ questions assisted in understanding the placement of this group of faculty along the continuum in their adoption of DLTs for online teaching. It was anticipated that faculty teaching online would self-report higher levels along the continuum, which included refocusing, collaboration, and consequence, as compared to the lower self-focusing levels (unconcerned, informational, and personal) or the middle level of task management.

H0 2: Online faculty will score at the higher impact stages of the CBAQ levels of concern.

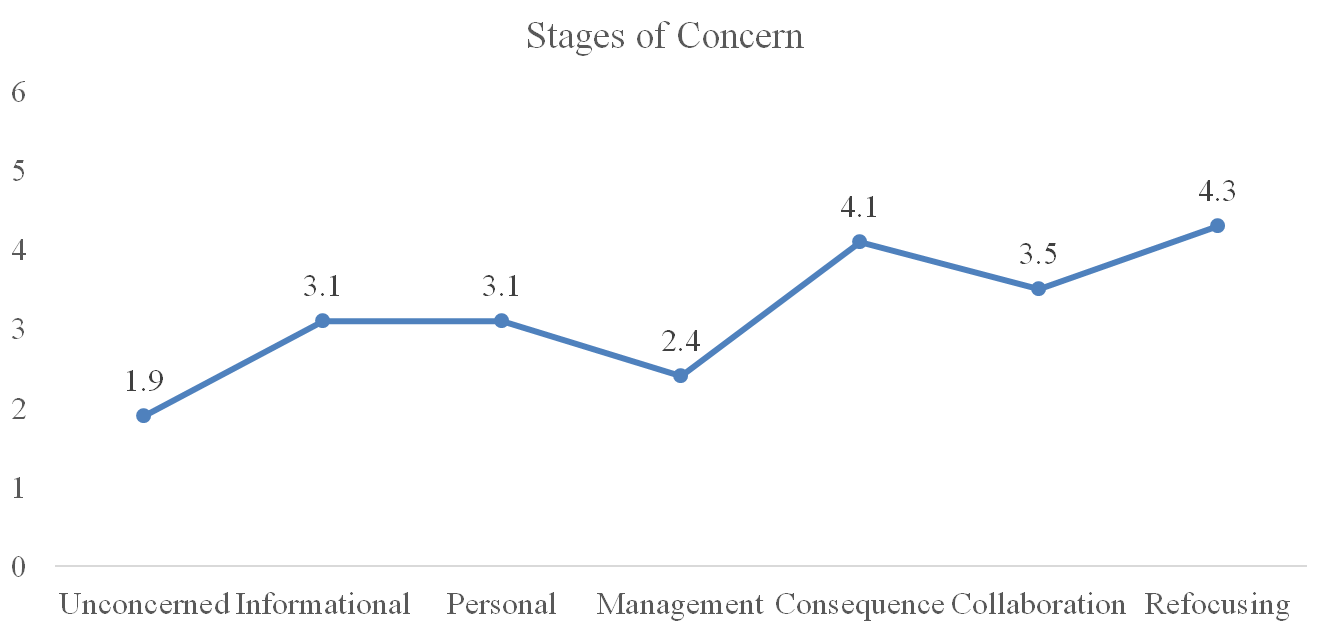

As illustrated in Table 3, the highest levels of implementation of innovations in distance learning were consequence (M = 4.1) and refocusing (M = 4.3), indicating that in this sample, faculty were more concerned with the consequences of using the innovation for students and had ideas about how to adapt their use of DLTs from their point of view. The lowest adoption level included was "unconcerned" (M = 1.9), which reflects that the participants were aware of the DLTs available for their use in teaching online but were not interested in exploring these tools. Management concerns were also low, which indicated that faculty were confident in their ability to manage learning activities and to support students in being successful online. H0 2 is supported by the data, as demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Stages of Concern Self-Reported by Faculty Teaching Online

Expression of Self-Efficacy in the Use of Distance Learning Tools

The researchers predicted that participants from this higher education institution at hand, who were experienced in teaching in an online higher education environment, would express confidence in using DLTs as a part of their teaching. These faculty members had access to professional development opportunities and the ability to implement the tools in their teaching. The combined effect was expected to be in the expression of confidence in the use of the tools.

H0 3: The online faculty would express high levels of technical self-efficacy in the use of DLTs in online teaching.

The participants indicated high levels of agreement with the statements related to their attitude toward solving technical issues. The ratings ranged from "irrelevant or not true about me" and "somewhat like me" to "very true about me" on the 7-point Likert scale. Across the six self-efficacy questions using a 7-point Likert scale, participants were more likely to report the statements as true of themselves (M = 4.65). The lowest rated statement was the ability to solve technical problems, with 21% of the respondents indicating this was not like them (M = 4.34). The highest rated statement was confidence in their technical ability to solve difficulties (M = 4.86), followed closely by the ability to handle unforeseen situations (M = 4.80), with 59% of the respondents rating themselves at a 5, 6, or 7 on the Likert scale for both items. The ability to seek another technical solution had the highest percentage of individuals (68%) scoring in the upper ranges of the scale (i.e., 5, 6, or 7). The data indicated that faculty were confident in their ability to use DLTs (see Table 3). The data supports H0 3.

Table 3:

Faculty self-efficacy using distance learning tools

| Self-Efficacy Questions | M |

| Rely upon technical abilities | 4.34 |

| Able to handle unforeseen technical situations | 4.77 |

| Able to deal with unexpected events | 4.46 |

| Able to use technology to accomplish goals | 4.80 |

| Able to seek alternative technology solutions | 4.66 |

| Able to solve technology problems | 4.86 |

Limitations

It is important to acknowledge that this study does have limitations. First, the relatively small sample size (N = 42) and response rate (16%) may impact the generalizability of the findings, as the data reflects a subset of faculty who were willing and able to respond during the rapid transition to distance learning. The reliance on self-reported survey data introduces the potential for response bias and recall bias, which may affect the accuracy of participants' responses regarding their self-efficacy, use of professional development, and adoption of DLTs. Additionally, while validated instruments were used, modifications to the General Self-Efficacy Scale and the focus on DLT-specific wording could impact the validity of the results. The timing of the survey, conducted during a period of significant disruption due to stay-at-home directives, may further influence participants' reported concerns and experiences. Finally, the study's scope is limited to one regional institution, where specific professional development opportunities and institutional support may not reflect those available at other universities, reducing the broader applicability of the findings.

Discussion

The data provided insight into the faculty's journey in learning how to use DLTs. The hypothesis that faculty would be more likely to use the easy-access instructional resources provided by the university is not supported. However, faculty used external university resources as well as those offered by the institution. This opens several possibilities. First, the university training may have served as a springboard for exploring other opportunities to enhance knowledge about the tools. A second possibility is that faculty wanted training that was content specific to the DLTs. A third consideration is that the training introduced the tools, but additional support was required to implement the use them in the online classroom through webinars, how-to manuals, or courses. Regardless, faculty that participated in this study demonstrated a willingness to learn as much as possible about the tools.

The application of the Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM) presented in the study offers valuable insights for the design of continuing education in the field of online teaching. As anticipated, faculty expressed high levels on the CBAM scale of adoption. They attended training and were experienced in the use of DLTs. The combination of those two variables appears to promote their willingness to share their experiences with others and to begin to innovate to provide optimal learning experiences for students. However, while some faculty have invested over 220 hours in professional development, others stated that they had not participated in such learning opportunities in the last five years. This underlines that faculty differ in their needs and preferences regarding the type and scope of professional development opportunities, including different learning formats (e.g., workshops, webinars, self-study materials) as well as different content focuses. To fulfill their training needs, faculty members used both internal and external resources available to them to ensure they were adequately prepared to teach online.

The faculty reported high levels of self-efficacy in the use of DLTs for online teaching across all identified dimensions of self-efficacy in the instrument. One possible interpretation may be that faculty already felt relatively confident in this area and was more likely to need support with the content and didactic design of online courses. Training courses should, therefore, offer individual advice and coaching to support lecturers in the specific use of DLTs in their respective disciplines.

The somewhat lower score for the ability to solve technical problems may be attributed to the use of "always" in that question, which does not appear in the other questions. In future studies, removing "always" from that question may result in higher scores, allowing a rating on a continuum like the other questions. The findings showed high scores in the "Consequence" and "Refocusing" areas of the CBAM framework. This may show that faculty reflect on the effects of DLTs on learning success and contribute their own ideas for the further development and adaptation of these tools. Since this reflection needs time and continuous confrontation with various situations and challenges arising in distance teaching, the findings suggest that further professional development decisions should not be designed as a one-off measure but should be part of a long-term support process. Universities should offer lecturers continuous support even after the introduction of new tools and methods, e.g., in the form of peer learning groups, experience exchange forums, or through providing up-to-date information and best practices. The findings imply that higher education administrators who are evaluating the return on investment for the professional development funds spent, offering a variety of training options for the tools used in distance learning supports faculty confidence in the use of those tools and their willingness, as competence in using them for good distance teaching.

Future Research

Understanding the dynamic between the professional development offered at the institution and outside of the institution will be valuable to the instructional design team. Are faculty members encountering training opportunities or being exposed to the tools and strategies for distance learning at conferences, for example, and then attending training at the institution? Or are they attending training to obtain a stipend and then seeking additional information outside of the institution? Is it possible that the institutional training is too general to meet the needs of all content areas and that faculty are seeking additional specialized information elsewhere than the institution? Faculty may also be learning about the pedagogical implications of a technology tool and then using how-to videos or other resources in a just in time format to develop the instructional strategies for their courses. Answering these questions can allow the institution to better direct its professional development resources to meet faculty needs more precisely. Costs may be saved by purchasing outside resources for what faculty are seeking in those formats and allowing the design teams to focus their attention on the skills that faculty are seeking internally.

Conclusion

This research study continues to support that professional development for faculty improves the likelihood they will have the self-efficacy required to teach in online learning environments. Faculty who had adopted distance learning as a delivery mode for their courses spent time participating in a variety of professional development opportunities both within and beyond what the university offers. To truly understand the interplay between the options offered by an institution and other sources of professional development will require additional study to better direct training dollars to the best options. This study also supports that faculty, who often used DLTs, experiment with DLTs to develop new instructional strategies to support student learning as evident in the higher levels of use in the CBAM model. Regardless of how faculty self-select their training in the use of DLTs, they develop the self-efficacy required to teach in online learning environments. As a result, money spent for professional development both within the institution and through other sources appears to promote the skills required to use the DLTs for online teaching. Future studies could explore why this group of experienced online educators to better understand seeks professional development beyond the university and determine what types of resources this group of adopters requires to continue their professional growth in the field.

References

Allen, C. D., & Penuel, W. R. (2015). Studying teachers' sensemaking to investigate teachers' responses to professional development focused on new standards. Journal of Teacher Education, 66(2), 136-149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487114560646

Anderson, S. (1997). Understanding teacher change: Revisiting the Concerns Based Adoption Model. Curriculum Inquiry, 27(3), 331-367. https://doi.org/10.1111/0362-6784.00057

Archambault, L., Kennedy, K., Shelton, C., Dalal, M., McAllister, L. & Huyett, S. (2016). Incremental progress: Re-examining field experiences in K-12 online learning contexts in the United States. Journal of Online Learning Research, 2(3), 303–326. Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/174116/

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/1977-25733-001.pdf

Capone, R., & Lepore, M. (2021). From distance learning to integrated digital learning:

A fuzzy cognitive analysis focused on engagement, motivation, and participation

during COVID-19 pandemic. Technology, Knowledge and Learning.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-021-09571-w

Creely, E., Henriksen, D., Crawford, R., & Henderson, M. (2021). Exploring creative

risk-taking and productive failure in classroom practice. A case study of the

perceived self-efficacy and agency of teachers at one school. Thinking Skills and

Creativity, 42, 100951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100951

Dunbar, M., Melton, T.D. (2018). Self-efficacy and training of faculty who teach online. In: Hodges, C. (eds) Self-Efficacy in Instructional Technology Contexts. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99858-9_2

Eynon, B., Iuzzini, J., Keith, H. R., Loepp, E., & Weber, N. (2023). Teaching, learning, equity and change: Realizing the promise of professional development. Every Learner Everywhere. https://www.everylearnereverywhere.org/wp-content/uploads/Final-Teaching-Learning-Equity-and-Change-27.pdf

George, A. A., Hall, G. E., & Stiegelbauer, Z. M. (2013). Measuring implementation in schools: The stages of concern questionnaire. Southwest Educational Development Laboratory.

Hall, G. E. & Hord, S. M. (2014). Implementing change: Patterns, principles and potholes (4th ed.) Pearson.

Harris, J. B., Phillips, M., Koehler, M. J., & Rosenberg, J. M. (2017). TPCK/TPACK research and development: Past, present, and future directions. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 33(3). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3907

Horvitz, B. S., Beach, A. L., Anderson, M. L., & Xia, J. (2015). Examination of faculty self-efficacy related to online teaching. Innovative Higher Education, 40(4), 305-316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-014-9316-1

Kebritchi, M., Lipschuetz, A., & Santiague, L. (2017). Issues and challenges for teaching successful online courses in higher education: A literature review. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 46(1), 4-29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239516661713

Kerrick, S. A., Miller, K. H., & Ziegler, C. (2015). Using continuous quality improvement (CQI) to sustain success in faculty development for online teaching. The Journal of Faculty Development, 29(1), 33-40. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1696889892?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals

King, K. P. (2017). Technology and innovation in adult learning. Jossey-Bass.

Ma, K., Chutiyami, M., Zhang, Y., & Nicoll, S. (2021). Online teaching self-efficacy during COVID-19: Changes, its associated factors and moderators. Education and Information Technologies, 26, 6675–6697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10486-3

Mitchell, L. D., Parlamis, J. D., & Claiborne, S. A. (2015). Overcoming faculty avoidance of online education: From resistance to support to active participation. Journal of Management Education, 39(3), 350–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562914547964

Olden, D., Gröninger, J., Henrich, M., Schlichting, A., Kollar, I. & Bredl, K. (2022). Professional development and its' role for higher education instructors' TPCK, self-efficacy and technology adoption as well as their technological and didactical implementation of distance teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. In E. Langran (Ed.), Proceedings of Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 427-432). San Diego, CA, United States: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/220760/

Osika, R., Johnson, R., & Buteau, R. (2009). Factors influencing faculty use of technology in online instruction: A case study. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 12(1). http://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/spring121/osika121.html

Pajares, F., & Schunk, D. H. (2002). Self and self-belief in psychology and education: A historical perspective. In Improving academic achievement (pp. 3-21). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012064455-1/50004-X

Petko, D., Egger, N., Schmitz, F. M., Totter, A., Hermann, T., & Guttormsen, S. (2015). Coping through blogging: A review of studies on the potential benefits of weblogs for stress reduction. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 9(2), article 5. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12269

Porter, W. W., & Graham, C. R. (2016). Institutional drivers and barriers to faculty adoption of blended learning in higher education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(4), 748-762. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12269

Porter, W. W., & Graham, C. R. (2016). Institutional drivers and barriers to faculty adoption of blended learning in higher education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(4), 748-762. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12269

Robertson, M. & Al-Zahrani, A. (2012). Self-efficacy and ICT integration into initial teacher education in Saudi Arabia: Matching policy with practice. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 28(7), 1136-1151. https://ajet.org.au/index.php/AJET/article/download/793/93

Sailer, M., Stadler, M., Schultz-Pernice, F., Franke, U., Schöffmann, C., Paniotova, V.,

Husagic, L., & Fischer, F. (2021). Technology-related teaching skills and attitudes:

Validation of a scenario-based self-assessment instrument for teachers. Computers in

Human Behavior, 115, 106625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106625

Sangkawetai, C., Neanchaleay, J., Koul, R., & Murphy, E. (2020). Predictors of K-12 Teachers' Instructional Strategies with ICTs. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 25(1), 149–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-018-9373-0

Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized self-efficacy scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user's portfolio (pp. 35-37). Causal and Control Beliefs. Windsor: NFER-NELSON.

Sendall, P., Shaw, R., Round, K., & Larkin, J. T. (2010). Fear factors: Hidden challenges to online learning for adults. In T. T. Kidd (Ed.), Online education and adult learning: New frontiers for teaching practices (pp. 81-100). IGI Global.

Song, K-o., Hur, E-J., & Kwon, B-Y. (2018). Does high-quality professional development make a difference? Evidence from TIMSS. Compare: A Journal of comparative and International Education, 48(6). https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2017.1373330

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7). 783-805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

Van Acker, F., van Buuren, H., Kreijns, K., & Vermeulen, M. (2013). Why teachers use

digital learning materials: The role of self-efficacy, subjective norm and attitude.

Education and Information Technologies, 18(3), 495–514.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-011-9181-9

Xu, D., & Jaggars, S. S. (2013). The impact of online learning on students' course outcomes: Evidence from a large community and technical college system. Economics of Education Review, 37, 46-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2013.08.001

Zee, M., & Koomen, H. M. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: A synthesis of 40 years of research. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 981-1015. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315626801