Abstract

As Ph.D. education continues to evolve, hybrid programs have gained popularity by offering flexibility and accessibility to diverse student populations. However, a critical gap exists in understanding how students develop and maintain academic relationships and scholarly community in these environments. Specifically, research has not sufficiently addressed how peer relationships, social presence, and academic community evolve in hybrid Ph.D. programs. This qualitative study examines how graduate students experienced a hybrid instructional technology Ph.D. program at an R1 university through the lens of the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework. Seventeen current and former students completed an open-ended survey, revealing four main themes: (a) a flexible, accessible program supporting degree completion; (b) self-direction as crucial for the rigorous hybrid curriculum; (c) a collaborative peer community enhancing motivation and academic progress; and (d) consistent faculty guidance is critical for meeting program demands. Participants valued the program's flexibility while emphasizing the importance of self-motivation and organization. Peer connections provided essential support, although limited interaction could hinder engagement. Faculty responsiveness proved essential for navigating complex program challenges. Recommendations include developing flexible curricula, fostering planned peer interaction, supporting self-directed learning skills, and ensuring consistent faculty guidance. These findings can inform hybrid Ph.D. program design to better support academic community development and enhance student success.

Keywords: hybrid learning, online learning, Ph.D. education, graduate students, student experience

Ph.D. Student Voices: The Highlights and Challenges of Navigating a Hybrid Doctorate

Entirely online and hybrid courses have grown in popularity (Lauwers et al., 2022), providing students with more flexible methods of participation (Allen et al., 2007; Barnard-Brak et al., 2009; Butz et al., 2016). Hybrid programs, defined as having between 30% and 79% of course content delivered online (Müller & Mildenberger, 2021), are increasingly viewed by academic leaders as valuable to institutions' long-term strategies, with results considered equal to or more rewarding than face-to-face instruction (Allen et al., 2007).

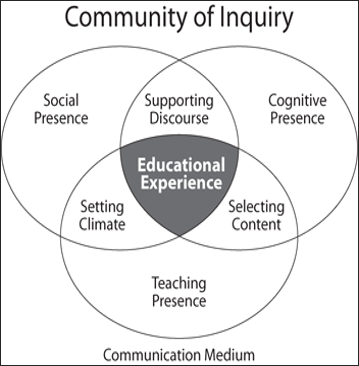

The Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework, developed by Garrison et al. (2001), guides this study by examining the three elements essential for meaningful learning experiences: Social, Cognitive, and Teaching Presence. Social Presence enables students to project their unique qualities into the community and present themselves as "real people." Cognitive Presence denotes how members construct meaning through sustained communication while Teaching Presence encompasses the planning, directing, and facilitation of social and cognitive processes to achieve educational outcomes.

Despite the growing adoption of hybrid Ph.D. programs, gaps remain in our understanding of how students experience and navigate these learning environments. While existing research has examined hybrid learning at the undergraduate and master's levels, Ph.D. education presents distinctive challenges, emphasizing scholarly community, mentorship, and independent research. Particularly understudied are (a) How Ph.D. students form and maintain peer relationships in hybrid environments, (b) How Social Presence develops when face-to-face interactions are limited, and (c) How academic community is created and evolves in hybrid Ph.D. programs.

This study addresses these gaps and explores how students experience a Ph.D. program that combines traditional in-person and online components. This research aims to understand students' experiences in this increasingly popular hybrid model, guided by the research question: "What are students' experiences of and opinions about participating in a hybrid Ph.D. program?" By examining candid perspectives, we seek to understand what this educational format means for Ph.D. students.

Hybrid Ph.D. Program Description

In the hybrid Ph.D. model, students are admitted in cohorts once per year in the Fall semester. The admitted students enroll together in the same instructional technology courses for the first three semesters in the program. Each graduate student is encouraged to enroll in two courses per semester. As seen in Table 1, the IT Ph.D. program curriculum consists of nine courses in instructional technology, four foundations courses, four research courses, and four educational leadership or higher education courses.

Table 1

Hybrid Ph.D. Program of Study (2018-2020)

| Academic Study Area | Number of 3-Credit Courses |

| Instructional Technology | 9 |

| Foundations | 4 |

| Research | 5 |

| Educational Leadership or Higher Education | 4 |

Originally a traditional on-campus program, the program evolved into a hybrid format as virtual technologies emerged. The program transitioned from five weekend meetings per semester to a blend of two to five Saturday sessions held in conjunction with online meetings throughout the semester. The online portions of the courses are delivered through Blackboard, developed collaboratively following instructional design principles and Quality Matters standards. They emphasize student-to-student and student-to-faculty interaction through group projects, discussions, and peer reviews.

While instructional technology courses were the first to be converted to the hybrid format, other content areas gradually adopted online and hybrid delivery. The program now features virtual orientations where new students interact with faculty and current students, virtual workshops focusing on dissertation work, and opportunities for research collaboration.

Literature Review

As higher education rapidly evolves, Ph.D. hybrid programs have gained significant traction as an alternative to traditional learning formats due to their transparency, fairness, and flexibility (Nurriden, 2023). Hybrid education combines face-to-face and virtual instruction through various media and online platforms (Viñas, 2021).

Collaborative Learning and the Hybrid Learning Format

Hybrid learning's strength lies in its potential to foster collaboration and enhance student participation (Abi Raad et al., 2021). Research indicates that alternating between face-to-face and online interactions can lead to more effective learning outcomes (Gleason & Greenhow, 2017; Sukiman et al., 2022). Hybrid programs also build a stronger sense of community compared to traditional or fully online courses (Rovai & Jordan, 2004), reducing dropout rates and improving student satisfaction.

The cohort-based structure standard in hybrid educational technology programs (Kung & Logan, 2014) plays a vital role in building supportive social connections. Studies indicate that hybrid courses often provide better quality interactions between students, peers, and instructors compared to traditional formats (Palmer et al., 2014). Student-instructor interactions, with acknowledgment and feedback, are essential for program success (Lee & Dashew, 2011; Studebaker & Curtis, 2021).

Benefits and Challenges of the Hybrid Learning Format

Hybrid programs remove physical, time, cultural, socio-economic, and geographic barriers, making Ph.D. education more accessible for diverse populations (Erichsen et al., 2014; Murphy et al., 2007). The hybrid format encourages self-efficacy (Vedubox, 2021), reinforces textbook concepts (González-Gómez et al., 2015), and enables longer information retention while enhancing learning enjoyment (Alvarez et al., 2013). However, concerns include potential decreases in work ethic and persistence (Lint, 2013), feelings of isolation, and communication difficulties (Panjaitan et al., 2021).

While existing literature provides insights into hybrid learning's general benefits and issues, three critical gaps emerge in relation to Ph.D. education:

- Most studies focus on course-level rather than program-level experiences, leaving questions about how students navigate the complete Ph.D. journey in hybrid formats.

- Research on peer relationships and scholarly community building has primarily examined traditional or fully online programs, with limited attention on hybrid formats.

- The application of the Community of Inquiry framework to hybrid Ph.D. education remains understudied, particularly regarding how Teaching, Social, and Cognitive Presence interact in these environments.

This study addresses these gaps by examining student experiences across their entire program journey, focusing on community building and peer relationships and applying the CoI framework to understand these experiences.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework guiding this study is the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework developed by Garrison et al. (2001). According to the CoI framework, three types of Presence are essential for creating a community of inquiry in online and hybrid courses: Teaching Presence, Social Presence, and Cognitive Presence, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1

CoI framework

Teaching Presence encompasses the design, facilitation, and direction of Cognitive and Social processes (Anderson et al., 2001). Instructors establish this through personal introductions, discussion facilitation, and clear expectations around self-directed learning (Stavredes, 2011). Social Presence enables participants to identify with the group, communicate purposefully, and develop personal relationships (Garrison, 2009). This involves developing connections between all participants through frequent interaction. Cognitive Presence refers to how instructors and students construct meaning through sustained discourse and reflection (Garrison et al., 2001). It emphasizes connecting through idea-sharing and discussion.

As these CoI characteristics support academic community-building, they are used in this research as a framework to examine the hybrid Ph.D. program as experienced by the study participants. Teaching, Social, and Cognitive presences provide specific lenses through which to examine and understand students' experiences in this hybrid doctoral program.

Methods

Approach

To effectively apply the CoI framework to our examination of student experiences, we designed a qualitative study that would capture the nuances of how students experience these three types of Presence in a hybrid doctoral program. Our research design aimed to analyze how students develop and maintain academic relationships, engage in scholarly discourse, and navigate the blend of online and face-to-face learning environments.

While previous studies have often relied on quantitative measures or focused solely on course evaluations, our qualitative approach using an open-ended survey enables a deeper exploration of how students navigate peer relationships, develop community, and experience various forms of Presence throughout their Ph.D. work. The survey questions (Appendix A) were designed to examine these areas, focusing on (a) the development and maintenance of peer relationships over time, (b) the formation of scholarly community in a hybrid environment, and (c) the interaction between different types of Presence in supporting Ph.D. success.

Participants

The study included 17 participants who were current and former students in the Instructional Technology Ph.D. program, recruited through a program Listserv. This number represents the total available population of students between 2016 and 2020 who responded to our invitation to participate. This timeframe was specifically chosen as it represents a period when the program had fully transitioned to offering more hybrid and online courses than in previous years, making these cohorts' experiences particularly relevant to our research questions. While 17 participants may appear a small number, it represents a strong response rate from the available population and aligns with qualitative research in which deeper insights are of more value than the number of participants.

Data Collection

Data were collected through a 10-question open-ended Qualtrics survey informed by the CoI framework. Survey items evaluated learning experiences in the hybrid Ph.D. program, tools and resources used to support learning, interaction with faculty and peers, and the benefits and challenges of hybrid Ph.D. education. Appendix B outlines how the ten hybrid Ph.D. survey questions align with the 34 CoI survey questions.

Data Analysis

We used content analysis to review survey responses and identify critical themes systematically. Content analysis was conducted following Creswell and Poth's (2018) process as shown in Table 2:

Table 2

Content Analysis Steps

| Step | Description |

| 1. Prepare Data | Transcribe interviews, normalize survey data etc. |

| 2. Define Unit of Analysis | Sentence, phrase, word most suitable for research question |

| 3. Read Through Data | Gain high level understanding of responses |

| 4. Initial Coding | Identify interesting segments of text and assign descriptive codes |

| 5. Code Refinement | Group coded data into categories and themes |

| 6. Themes Refinement & Evaluation | Develop clear theme names, evaluate coherence |

| 7. Report Findings | Present excerpts to support analysis |

Three researchers analyzed the data using both hand-coding and NVivo software, engaging in reflexive and iterative analysis to identify final codes, categories, and themes that addressed the study's guiding research question. Results of the hand-coded and NVivo analysis were reviewed and discussed by three of the researchers, resulting in the identification of final codes, categories, and themes. It is important to note that although the research analysis for this study is presented in a linear, step-by-step method, the examination of data was a reflexive and iterative process.

Findings

The research findings describe 17 graduate students' experiences of and opinions about participating in a hybrid Ph.D. program between the years of 2016-2020. Four themes (see Table 3) resulted from the survey response analysis. The following sections describe each theme as experienced by students in a hybrid Ph.D. program.

Table 3

Final Codes, Categories and Themes

| Codes | Categories and Subcategories | Final Themes and Subthemes |

Flexibility/convenience Accessible Faculty Interactions Peer Interactions Self-direction Personal growth Career advancement Work-life balance Sense of community Intellectual challenge Peer engagement Faculty support Self-directed learning | Positive Hybrid Experience

Challenges of Hybrid Experience

| A Flexible, Accessible Program Supports Degree Completion

Self-Direction is Necessary for Rigorous Hybrid Curriculum

A Collaborative Peer Community Enhances Motivation and Academic Progress

Consistent Faculty Guidance is Critical for Meeting Program Demands

|

Theme 1. Flexibility and Accessibility

Participants consistently highlighted the program's flexibility as a key factor in their ability to pursue Ph.D. studies. For example, one student noted: "The hybrid design of the program allowed me to have a learning experience. Due to my work and family life, attending face-to-face courses isn't an option for me." This sentiment was echoed by several participants who emphasized how the program's structure enabled them to balance their studies with professional and personal responsibilities.

Theme 2. Self-Directed Learning

The hybrid nature of the program necessitated a high degree of self-direction from students. Participants frequently mentioned the need for strong time management and organizational skills. As one student explained: "I was self-directed which meant planning and organization. A few of the courses have end-of-semester deadlines which meant I had to carve time out ahead of time to achieve my set targets."

Theme 3. Peer Collaboration and Support

While the hybrid format presented some roadblocks for peer interaction, many participants valued the connections they were able to form with classmates. One student described: "Perhaps the most significant contributor to my success was the bond that developed between the entire cohort. The trust and camaraderie we felt laid the groundwork for mutual support for our learning." However, some participants noted that limited face-to-face interaction could stand in the way of engagement: "Not having a cohort that I can constantly meet and talk to may have hindered my learning motivation in some of the courses."

Theme 4. Faculty Guidance and Responsiveness

Participants emphasized the crucial role of faculty in their learning experience. Many reported positive interactions, as exemplified by this comment: "The faculty in my program were nothing but supportive of my studies. My advisor worked closely with me to chart a course through the program that worked for me." However, some participants noted that it took extra effort to build relationships with faculty in the hybrid format: "Reduced personal contact with some professors" was cited as a challenge by one participant.

These findings highlight the relationship between program flexibility, self-direction, peer support, and faculty guidance in shaping students' experiences in hybrid Ph.D. education.

Discussion

The results of this study provide valuable insights into students' experiences in a hybrid Ph.D. program, by illustrating how the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework is used and supported in this educational context. Our findings both align with and extend some aspects of the CoI model while highlighting other areas where the hybrid format can present concerns and opportunities for Ph.D. education.

Flexibility and Accessibility: Extending Teaching Presence

The theme of Flexibility and Accessibility relates to the Teaching Presence element of CoI, particularly in terms of instructional design and organization. Our finding also suggests that in hybrid Ph.D. programs, Teaching Presence extends beyond individual instructor behaviors to encompass program-level design decisions that facilitate student engagement and success.

Participants consistently highlighted the program's flexibility as a critical factor in their ability to pursue Ph.D. studies. As one of the participants noted, "I preferred that the majority of the courses were online. This enabled me to still take care of my responsibilities as a mom, wife, and full-time teacher." This aligns with previous research indicating that hybrid learning appeals to students with multiple responsibilities (Hall & Villareal, 2015) and removes various barriers to Ph.D. education (Murphy et al., 2007).

Our findings extend the concept of Teaching Presence by demonstrating how it can be embedded in the overall program structure. The hybrid format, with its mix of online and face-to-face components, represents a form of Teaching Presence that considers learners' needs and contexts. This suggests that in hybrid Ph.D. programs, Teaching Presence begins at the program design level, creating an environment that supports student engagement even before individual courses begin. This extension of Teaching Presence to program-level design aligns with recent literature emphasizing the importance of purposeful design in online and hybrid Ph.D. programs (Kumar & Dawson, 2018).

Self-Directed Learning: Cognitive Presence and Student Agency

While not explicitly part of the CoI framework, Self-Directed Learning closely relates to and extends our understanding of Cognitive Presence in hybrid Ph.D. education. Our findings suggest that successful Cognitive Presence in this context relies heavily on students' ability to self-regulate and manage their learning processes. Participants consistently emphasized the need for self-direction and time management. As one respondent commented, "I was self-directed which meant planning and organization. A few of the courses have end-of-semester deadlines which meant I had to carve time out ahead of time to achieve my set targets." This aligns with Hall and Villareal's (2015) finding that self-regulation is crucial for success in hybrid courses.

However, our results suggest that in hybrid Ph.D. programs, the relationship between self-direction and Cognitive Presence is more pronounced than in traditional settings. The hybrid format amplifies the need for students to take charge of their learning process, actively constructing knowledge and meaning.

This extends our understanding of Cognitive Presence by highlighting the critical role of student agency in achieving deep, meaningful learning in hybrid Ph.D. contexts. These findings both support and challenge existing literature. They align with research showing that hybrid learning can increase student participation and self-efficacy (Abi Raad et al., 2021; Vedubox, 2021). However, they also suggest that the level of self-direction required in hybrid Ph.D. programs may be higher than previously recognized, potentially presenting challenges for students who struggle with self-regulation.

This emphasis on self-direction in relation to Cognitive Presence extends the CoI framework by suggesting that in hybrid Ph.D. programs, student-driven processes may be as crucial as instructor-facilitated ones in promoting critical thinking and knowledge construction. It also questions how programs can best support students in developing these crucial self-regulatory skills.

Peer Collaboration and Support: Enhancing Social Presence

Peer Collaboration and Support align with the Social Presence element of CoI. However, our findings suggest that establishing Social Presence in a hybrid program may require additional effort and intentional design, as the limited face-to-face interaction can hinder the ability to build a sense of community. Participants highlighted the value of peer connections in providing support, motivation, and a sense of belonging. As one the participants noted, "Perhaps the most significant contributor to my success was the bond that developed between the entire cohort. The trust and camaraderie we felt laid the groundwork for mutual support for our learning." This aligns with previous research indicating that hybrid programs can foster a greater sense of community than traditional or fully online courses (Rovai & Jordan, 2004).

Our findings also reveal the issue of maintaining a robust Social Presence in a hybrid format. Some participants reported feelings of isolation or limited opportunities for peer interaction. As one student expressed, "Not having a cohort that I can constantly meet and talk to may have hindered my learning motivation in some of the courses." This suggests that while hybrid programs have the potential to foster strong social connections, achieving this requires deliberate strategies and program design.

These results both support and extend the existing literature on Social Presence in online and hybrid learning. They align with research emphasizing the importance of social interaction in strengthening the learning process (Rausch & Crawford, 2012). However, they also highlight the concerns about fostering Social Presence in hybrid Ph.D. programs, where the balance between online and face-to-face interaction may need a more deliberate focus.

Our findings suggest that the CoI framework's conception of Social Presence may need to be expanded for hybrid Ph.D. contexts. While the framework recognizes the importance of community, our results indicate that in hybrid programs, Social Presence may need to be actively cultivated through a combination of face-to-face interactions, online collaboration tools, and intentional community-building activities. This extends our understanding of how Social Presence operates in hybrid learning environments and suggests areas for further research and program development.

Faculty Guidance and Responsiveness: The Interplay of Teaching and Social Presence

Faculty Guidance and Responsiveness relate to both Teaching Presence and Social Presence in the CoI model. The importance participants placed on faculty support underscores the critical role of Teaching Presence in hybrid Ph.D. education. However, some students' barriers in building relationships with faculty suggest that maintaining a solid Teaching and Social Presence in a hybrid format may require specific strategies that differ from those used in fully online or face-to-face programs. Participants consistently emphasized the importance of faculty guidance and responsiveness. As one of the respondents stated, "The faculty in my program were nothing but supportive of my studies. My advisor worked closely with me to chart a course through the program that worked for me." This aligns with previous research highlighting the importance of instructor acknowledgment and feedback in hybrid and online programs (Lee & Dashew, 2011; Studebaker & Curtis, 2021).

Our results also reveal barriers to maintaining consistent faculty-student connections in a hybrid format. Some participants reported difficulties building meaningful relationships with faculty or lacking personal contact. This suggests that while Teaching Presence is crucial in hybrid Ph.D. programs, achieving it may require different strategies than those used in traditional or fully online settings. These findings both support and extend the existing literature on Teaching Presence in online and hybrid learning. They align with research emphasizing the importance of faculty responsiveness and accessibility (Makhdoom et al., 2013). However, they also highlight the need to maintain a strong Teaching Presence in hybrid Ph.D. programs, where the balance between online and face-to-face interactions may affect the quality of faculty-student relationships.

Our results suggest that in hybrid Ph.D. programs, Teaching Presence and Social Presence may be more closely intertwined than the CoI framework typically represents. Faculty guidance facilitates learning (Teaching Presence) and plays a crucial role in helping students feel connected to the academic community (Social Presence). This connection is vital in hybrid formats, where opportunities for spontaneous interaction may be limited. These findings extend the CoI framework by suggesting that in hybrid Ph.D. programs, strategies for fostering Teaching Presence may need to explicitly consider how to build and maintain social connections between faculty and students. This has implications for faculty training, program design, and the development of support systems for both students and instructors in hybrid Ph.D. education.

Our study provides valuable insights into how the CoI framework is applied in hybrid Ph.D. programs, highlighting areas where the model may need expansion or refinement to capture the complexities of this educational format fully. By highlighting the interplay between program design, self-directed learning, peer collaboration, and faculty guidance, our findings contribute to a more complex understanding of how to create effective and engaging hybrid Ph.D. learning experiences. Future research could further explore strategies for enhancing each Presence in hybrid contexts and investigate how these elements interact to support Ph.D. student success.

Theoretical Contributions

This study adds to our understanding of how learning theories apply to hybrid Ph.D. education. Our findings build on two critical theories while offering fresh insights into hybrid learning environments. First, our results expand Self-Regulated Learning (SRL) theory (Zimmerman, 1989) by showing how Ph.D. students manage their own learning in hybrid programs. We found that these programs demand even higher levels of self-regulation than traditional or fully online formats, particularly regarding time management and staying motivated. The blend of online and face-to-face learning creates an environment in which student self-regulation skills are necessary for success.

Second, we contribute to the Theory of Transactional Distance (Moore, 1997) by revealing how the communication space between instructors and learners in hybrid programs can fluctuate. While this theory typically focuses on fully online education, our findings show that hybrid programs create a dynamic environment where the communication space between instructors and students constantly shifts.

Our findings related to peer collaboration also add to our understanding of social learning in hybrid environments. The mix of online and face-to-face interactions suggests we need to think differently about how students learn from each other when they move between virtual and physical spaces.

Conclusion

This study set out to address a gap in the literature regarding students' experiences in hybrid Ph.D. programs, focusing on the development of peer relationships, Social Presence, and academic community. Our research question asked, "What are students' experiences and opinions about participating in a hybrid Ph.D. program?" Through a qualitative exploration of 17 graduate students' experiences in a hybrid instructional technology Ph.D. program, we provided valuable insights confirming and extending current knowledge about hybrid Ph.D. education.

Our findings directly address the research question by offering a comprehensive view of students' experiences and perceptions through our identified themes:

- A Flexible, Accessible Program Supports Degree Completion

- Self-direction is Necessary for a Rigorous Hybrid Curriculum

- A Collaborative Peer Community Enhances Motivation and Academic Progress

- Consistent Faculty Guidance is Critical for Meeting Program Demands

The study provides insight into program structure, student self-direction, peer collaboration, and faculty support in hybrid Ph.D. education. We have shown that while the flexibility of hybrid programs is highly valued and supports degree completion, it also requires significant self-direction from students. This finding extends how Cognitive Presence is experienced in hybrid Ph.D. contexts, suggesting that student agency is more critical than previously recognized.

Our research has also addressed the gap related to peer relationships and Social Presence in hybrid Ph.D. programs. We found that while a collaborative peer community significantly enhances motivation and academic progress, establishing and maintaining these connections in a hybrid format requires deliberate effort and strategic program design. This insight offers a more complex understanding of Social Presence in hybrid Ph.D. education.

The study also highlights the crucial role of faculty guidance in hybrid programs, demonstrating how Teaching Presence extends beyond individual course instruction to include program-level support and mentorship. This finding addresses the gap in understanding how an academic community is cultivated in hybrid Ph.D. programs, revealing the delicate balance between faculty support and independent student work.

By applying the Community of Inquiry framework to hybrid Ph.D. education, we have identified areas where the model may need refinement to capture this educational format's dynamics fully. Our research suggests that in hybrid Ph.D. programs, the elements of Teaching Presence, Social Presence, and Cognitive Presence are more profoundly interwoven and student-driven than in traditional educational settings.

Finally, this study provides a basis for understanding the distinct challenges and opportunities presented by hybrid Ph.D. programs. These insights can inform program design, policy development, and provide a valuable roadmap for creating effective, engaging, and supportive learning environments that balance flexibility with rigorous academic standards.

Implications

1. Enhancing Self-Directed Learning Support

The findings of our study have implications for the design and implementation of hybrid Ph.D. programs, particularly in enhancing self-directed learning support. The critical role of self-direction in student success emphasizes the need for targeted student support. We recommend implementing an orientation module focused on self-directed learning strategies, encompassing time management techniques, goal-setting practices, and motivational strategies. This proactive approach can help students navigate the hybrid Ph.D. education from day one. Programs can also consider developing policies that include regular check-ins between students and advisors, creating a structured opportunities for discussions and questions.

2. Fostering Peer Collaboration in Hybrid Environments

Our study's findings regarding peer collaboration in hybrid Ph.D. environments highlight both the value of peer support and the problems students face in building and maintaining connections. These insights indicate the critical need for intentional strategies to foster strong peer networks in hybrid programs. To address this, we recommend implementing a structured peer mentoring program that pairs advanced Ph.D. students with new students. This approach can create a supportive community from the outset of the program. Additionally, institutions should consider establishing guidelines that incorporate collaborative projects into coursework, ensuring that each course includes at least one significant peer-to-peer interaction component. This would create consistent opportunities for meaningful collaboration throughout the program, helping to reduce feelings of isolation that some students reported.

3. Optimizing Faculty Engagement and Responsiveness

Our research findings underscore the critical role of faculty guidance in hybrid Ph.D. programs while revealing obstacles some students face in maintaining consistent faculty connections. This contrast highlights the need for targeted strategies to optimize faculty engagement and responsiveness in hybrid learning environments. To address these concerns, we recommend implementing comprehensive professional development opportunities for faculty, focusing on effective communication and mentoring strategies tailored to hybrid settings. These training programs can equip faculty with the skills needed to bridge hybrid education's physical and virtual aspects, ensuring they can provide consistent, high-quality support to students across all interaction methods. Furthermore, institutions should consider developing and implementing clear policies that set expectations for faculty responsiveness in hybrid programs. These include guidelines for maximum response times to student questions and regular virtual office hours requirements.

4. Balancing Flexibility with Structure in Program Design

Our study reveals a complex perspective on program design in hybrid Ph.D. education, where students deeply value the flexibility offered by the format while simultaneously expressing a need for more structured support to facilitate their progress. This insight underscores the importance of striking a delicate balance between flexibility and structure in hybrid program design. To address this, we recommend implementing a flexible milestone system that allows students to set personalized deadlines within a broader framework of program requirements.

This approach can provide the structure needed to keep students on track while respecting their individual circumstances and learning paces. Additionally, institutions should consider developing policies that support the creation of individualized study plans for each Ph.D. student. These plans aim to balance program requirements with personal and professional commitments, offering an approach to Ph.D. education that maximizes both flexibility and accountability. This balanced approach to program design acknowledges the advantages of hybrid learning while providing the necessary scaffolding to support students through the rigorous demands of Ph.D. study.

Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights into students' experiences in a hybrid Ph.D. program, several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. The study included only 17 participants from a single hybrid Ph.D. program in Instructional Technology. This small sample size limits the generalizability of the findings to other hybrid Ph.D. programs or disciplines. Additionally, the study relied on participants' recollections of their experiences, which may be subject to recall bias. Participants' memories and perceptions of their experiences could have changed over time, affecting the accuracy of their responses.

The study's focus on students enrolled between 2016 and 2020 presents a relatively short timeframe that may not capture long-term trends or changes in the program or students' experiences over an extended period. Furthermore, as the researchers are likely affiliated with the program being studied, there is a potential for bias in data interpretation. This insider perspective, while valuable, may have influenced the analysis and presentation of results. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights into students' lived experiences in a hybrid Ph.D. program, offering a foundation for future research in this area.

Future Research

While this study addresses significant gaps in understanding hybrid Ph.D. education, several areas deserve further investigation. Future research should examine how peer relationships and scholarly communities develop across different disciplines and program structures, as the current study's focus on instructional technology may not capture specific issues in other fields. Longitudinal studies could track how students' self-regulation strategies and needs evolve throughout their Ph.D. journey, providing insights into when and how to best support student development. Additionally, comparative studies examining hybrid, traditional, and fully online Ph.D. programs could help identify the aspects of hybrid formats that most impact student success. Research is also needed to investigate how different ratios of online to face-to-face interaction affect student experiences and outcomes.

Given the crucial role of faculty guidance revealed in our study, future research should explore effective faculty development strategies for hybrid Ph.D. education, particularly examining how to help faculty balance flexibility with structure. These research directions would further address gaps in our understanding of hybrid Ph.D. education while providing practical insights for program improvement.

References

Abi Raad, M. E., & Odhabi, H. (2021). Hybrid learning here to stay! Frontiers in Education Technology, 4(2), 121. doi:10.22158/fet.v4n2p121

Ahmed, A. M., & Osman, M. E. (2020). The effectiveness of using wiziq interaction platform on students' achievement, motivation and attitudes. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 21(1), 19-30. doi.org/10.17718/tojde.690112

Allen, I. E., Seaman, J., & Garrett, R. (2007). Blending in the extent and promise of blended education in the United States. American Journal of Educational Research, 1(10), 413-418.

Alvarez, A., Martin, M., Fern ́andez-Castro, I., & Urretavizcaya, M. (2013). Blended traditional teaching methods with learning environments: experience, cyclical evaluation process and impact with MAgAdI. Computers & Education, 68, 129-140. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2013.05.006

Anderson, T., Rourke, L., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing Teaching Presence in a computer conferencing context. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 5(2). doi:10.24059/olj.v5i2.1875

Arbaugh, J. B., Cleveland-Innes, M., Diaz, S. R., Garrison, D. R., Ice, P., Richardson, & Swan, K. P. (2008). Developing a community of inquiry instrument: Testing a measure of the Community of Inquiry framework using a multi-institutional sample. The Internet and Higher Education, 11(3-4), 133-136. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.06.003

Avery, C. (2023). Ph.D. students' experiences of community of practice in a hybrid cohort-based program: A case study. Graduate theses and dissertations. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/5070

Barnard-Brak, L., Lan, W., To, Y., Paton, V., & Lai, S. (2009). Measuring self-regulation in online and blended learning environments. The Internet and Higher Education, 12, 1-6. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.10.005.

Blier, H. M. (2008). Webbing the common good: Virtual environment, incarnated community, and education for the reign of God. Teaching theology and religion, 11, 24-31. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9647.2007.00393.x

Butz, N., Stupnisky, R., Pekrun, R., Jensen, J., & Harsell, D. (2016). The impact of emotions on student achievement in synchronous hybrid business and public administration programs: A longitudinal test of Control-Value Theory. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 14, 441-474. doi:10.1111/dsji.12110

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks.

Elmore, R. L. (2021). Reflections on mentoring online Ph.D. learners through the dissertation. Christian Higher Education, 20(1-2), 57-68. doi:10.1080/15363759.2020.1852132

Erichsen, E. A., Bolliger, D. U., & Halupa, C. (2014). Student satisfaction with graduate supervision in Ph.D. programs primarily delivered in distance education settings. Studies in Higher Education, 39(2), 321-338. doi:10.1080/03075079.2012.709496

Garrison, D. R. (2007). Online Community of Inquiry review: Social, Cognitive, and Teaching Presence issues. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(1), 61-72.

Garrison, D. R. (2009). Communities of Inquiry in online learning. Encyclopedia of Distance Learning, 352-355. doi:10.4018/978-1-60566-198-8.ch052

Garrison, D. R., & Akyol, Z. (2013). The Community of Inquiry theoretical framework. Handbook of Distance Education, 104-119.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education model. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1096751600000166

Gleason, B., & Greenhow, C. (2017). Hybrid learning in higher education: The potential of teaching and learning with robot-mediated communication. Online Learning Journal, 21(4), 159-176. doi:10.24059/olj.v21i4.1276

González-Gómez, D., Airado, D., Cañada-Cañada, F., & Su-Jeong, J. (2015). A comprehensive application to assist in acid-base titration self-learning: An approach for high school and undergraduate students. Journal of Chemical Education, 92(5), 855-863. doi:10.1021/ed5005646

Hall, S., & Villareal, D. (2015). The hybrid advantage: Graduate student perspectives of hybrid education courses. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 27(1), 69-90. Retrieved from http://www.isetl.org/ijtlhe/

Henriksen, D., Mishra, P., Greenhow, C., Cain, W., & Roseth, C. (2014). A tale of two courses: Innovation in the hybrid/online Ph.D. program at Michigan State University. TechTrends,58(4), 45-53. doi:10.1007/s11528-014-0768-z

Hilli, C., Nørgård, R. T., & Aaen, J. H. (2019). Designing hybrid learning spaces in higher education. Dansk Universitetspædagogisk Tidsskrift, 14(27), 66-82. doi:10.7146/dut.v14i27.112644

Hung, H.-T. (2015). Flipping the classroom for English language learners to foster active learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 28(1), 81-96. doi:10.1080/09588221.2014.967701

Koehler, M. J., Zellner, A. L., Roseth, C. J., Dickson, R. K., Dickson, W. P., & Bell, J. (2013). Introducing the first hybrid Ph.D. program in educational technology. TechTrends, 57(3). doi:10.1007/s11528-013-0662-0

Kung, M., & Logan, T. J. (2014). An overview of online and hybrid Ph.D. degree programs in educational technology. TechTrends, 58(4), 16-18. doi:10.1007/s11528-014-0764-3

Lauwers, T., Edelson, P., Kupczynski, M., Rainey, C., & Voloch, S. (2022, March 24). Demand for online education is growing. Are providers ready? McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/education/our-insights/demand-for-online-education-is-growing-are-providers-ready

Lederman, D. (2019, December 11). Online enrollments grow, but pace slows. InsideHigherEd. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2019/12/11/more-students-study-online-rate-growth-slowed-2018

Lee, R., & Dashew, B. (2011). Designed learner interaction in blended course delivery. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 15(1), 68-76. doi:10.24059/olj.v15i1.183

Lint, A. H. (2013). E-learning student perceptions on scholarly persistence in the 21st century with social media in higher education. Creative Education, 04(11). doi:10.4236/ce.2013.411102

Lotrecchiano, G. R., McDonald, L. L., Lyons, L., Long, T., & Zajicek-Farber, M. (2013). Blended learning: Strengths, challenges, and lessons learned in an interprofessional training program. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17, 1725-1734. doi:10.1007/s10995-012-1175-8

Makhdoom, N., Khoshhal, K. I., Algaidi, S., Heissam, K., & Zolaly, M. A. (2013). Blended learning' as an effective teaching and learning strategy in clinical medicine: A comparative cross-sectional university-based study. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 8(1), 12-17. doi:10.1016/j.jtumed.2013.01.002

Meydanlıoğlu, A., & Arıkan, F. (2014). Effect of hybrid learning in higher education. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, International Journal of Social, Behavioral, Educational, Economic, Business and Industrial Engineering, 8, 1292-1295. doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1092346

Mohajan, H. K. (2018). Qualitative research methodology in social sciences and related subjects. Journal of Economic Development, Environment, and People, 7, 23-48. doi:10.26458/jedep.v7i1.571

Moore, M. (1997). Theory of transactional distance. In D. Keegan, (Ed.) Theoretical principles of distance education, (pp. 22-38). Routledge.

Mu, K., Coppard, B. M., Bracciano, A. G., & Bradberry, J. C. (2014). Comparison of on-campus and hybrid student outcomes in occupational therapy Ph.D. education. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68, S51-S56. doi:10.5014/ajot.2014.685S02

Müller, C., & Mildenberger, T. (2021). Facilitating flexible learning by replacing classroom time with an online learning environment: A systematic review of blended learning in higher education. Educational Research Review, 34. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100394

Murphy, M. J., Levant, R. F., Hall, J. E., & Glueckauf, R. L. (2007). Distance education in professional training in psychology. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38, 97-103. doi:0.1037/0735-7028.38.1.97

Myers, L. H., Jeffery, A. D., Nimmagadda, H., Werthman, J. A., & Jordan, K. (2015). Building a community of scholars: One cohort's experience in an online and distance education doctor of philosophy program. The Journal of Nursing Education, 54(11), 650-654. doi:10.3928/01484834-20151016-07

Nuruddin, N. (2024). Hybrid learning (HL) in higher education: The design and challenges. International Journal of Instruction, 17(1), 97-114. doi:10.29333/iji.2024.1716a

Palmer, M. M., Shaker, G., & Hoffman-Longtin, K. (2014). Despite faculty skepticism: Lessons from a graduate-level seminar in a hybrid course environment. College Teaching, 62, 100-106. doi:10.1080/87567555.2014.9126 08

Panjaitan, E. S., Murdiaty, & Purnaya. (2021). Preparation for online lectures at higher education using the Microsoft Teams application for high school graduates. Journal of Education and Community Service, 4(2). doi:10.29303/jppm.v4i2.2643

Paul, P., Olson, J., Spiers, J., & Hyde, A. (2021). Becoming scholars in an online cohort of a Ph.D. in nursing program. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 18(1), 20210024. doi:10/1515/ijnes-2021-0024

Rausch, D. W. & Crawford, E. K. (2012). Cohorts, communities of inquiry, and course delivery methods: UTC best practices in learning-the hybrid learning community model. Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 60, 175-180. doi:10.1080/07377363.2013.722428

Rovai, A. P. & Jordan, M. (2004). Blended learning and sense of community: A comparative analysis with traditional and fully online graduate courses. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 5. http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/192/274. doi:10.19173/irrodl.v5i2.192

Studebaker, B., & Curtis, H. (2021). Building community in an online Ph.D. program. Christian Higher Education, 20(1-2), 15-27. doi:10.1080/15363759.2020.1852133

Sukiman, Haningsih, S., & Rohmi, P. (2022). The pattern of hybrid learning to maintain learning effectiveness at the higher education level post-COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Educational Research, 11(1). doi:10.12973/eujer.11.1.243

The Condition of Education. (2016). (NCES 2016-144). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Washington, DC. Retrieved (2024, January 28) from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2016/2016144.pdf

Viñas, M. (2021). Challenges and possibilities of hybrid education in times of pandemic. Plurents. Artesy Letras, 12, 027. doi:10.24215/18536212e027

Woo, B., Evans, K., Wang, K., & Pitt-Catsouphes, M. (2021). Online and hybrid education in a social work Ph.D. program. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(1), 138-152. doi:10.1080/10437797.2019.1661921

Zimmerman B. J. (1989). A social cognitive view of self-regulated academic learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 329-339. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.81.3.329

Appendix A

Survey Questions

Question 1 - What personal or professional factors led you to choose UA's Instructional Leadership with an Instructional Technology concentration program?

Question 2 - How would you characterize your learning experience as a student in a hybrid Ph.D. program?

Question 3 - In what ways, if any, did the hybrid design of the program enhance your learning experience?

Question 4 - In what ways, if any, did the hybrid design of the program detract from or hinder your learning experience?

Question 5 - What tools and resources did you use to facilitate your learning in the hybrid program and how effective were they?

Question 6 - Describe your experiences and interactions with program faculty in the hybrid program.

Question 7 - How frequently did you interact with the faculty and was this frequency sufficient for your needs?

Question 8 - What tools did you use to facilitate your interaction with the faculty and how effective were they?

Question 9 - What do you see as the benefits of a hybrid Ph.D. program, in general, and for you personally?

Question 10 - What do you see as the challenges of a hybrid Ph.D. program, in general, and for you personally?

Appendix B

Hybrid Ph.D. Survey Questions and Corresponding CoI Survey Questions

| Hybrid Ph.D. Survey Question | CoI Survey Questions | |

| 1. What personal or professional factors led you to choose (this) Instructional Leadership with an Instructional Technology concentration program? | N/A | |

| 2. How would you characterize your learning experience as a student in a hybrid Ph.D. program? | 11. The instructor helped to focus discussion on relevant issues in a way that helped me to learn. 27. Brainstorming and finding relevant information helped me resolve content related questions. | Teaching Cognitive |

| 3. In what ways, if any, did the hybrid design of the program enhance your learning experience? | 4. The instructor clearly communicated important due dates/time frames for learning activities 8. The instructor helped keep the course participants on task in a way that helped me to learn. | Teaching |

| 4. In what ways, if any, did the hybrid design of the program detract from or hinder your learning experience? | 4. The instructor clearly communicated important due dates/time frames for learning activities | Teaching |

| 5. What tools and resources did you use to facilitate your learning in the hybrid program and how effective were they? | 3. The instructor provided clear instructions on how to participate in course learning activities 12. The instructor provided feedback that helped me understand my strengths and weaknesses relative to the course's goals and objectives | Teaching Teaching |

| 6. Describe your experiences and interactions with program faculty in the hybrid program. | 10. Instructor actions reinforced the development of a sense of community among course participants 14. Getting to know other course participants gave me a sense of belonging in the course | Teaching Social |

| 7. How frequently did you interact with the faculty and was this frequency sufficient for your needs? | 13. The instructor provided feedback in a timely fashion | Teaching |

| 8. What tools did you use to facilitate your interaction with the faculty and how effective were they? | 3. The instructor provided clear instructions on how to participate in course learning activities | Teaching |

| 9. What do you see as the benefits of a hybrid Ph.D. program, in general, and for you personally? | 3. The instructor provided clear instructions on how to participate in course learning activities. 10. Instructor actions reinforced the development of a sense of community among course participants 16. Online or web-based communication is an excellent medium for social interaction. 22. Online discussions help me to develop a sense of collaboration. | Teaching Teaching Social Social |

| 10. What do you see as the challenges of a hybrid Ph.D. program, in general, and for you personally? | 4. The instructor clearly communicated important due dates/time frames for learning activities (lack of clarity could be a challenge) 13. The instructor provided feedback in a timely fashion | Teaching Teaching |