Abstract

This is a design case of the development, implementation, and evaluation of an online course for nursing educators at a large southeastern college. The course teaches best practices for organizing online instruction with a focus on the Quality Matters standards. Implementation with a small group of instructors resulted in positive responses that caused the graduate faculty to make the unprecedented unanimous decision to implement a template based on the course’s content and design. Results of the evaluation are covered in detail and a discussion of the benefits and challenges of template use is offered.

Keywords: nursing education; online course design; instructional design; quality matters; higher education

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This study did not receive external funding.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to John Smoot. Email: SMOOTJ19@ECU.EDU

Improving Online Course Design in a Nursing Education Program: A Design Case

The nursing profession is in a state of crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated an already overwhelming shortage that leaves many hospital systems with significant gaps in nursing coverage. Meanwhile, nursing education is experiencing a period of tremendous change. There is a considerable curriculum shift to competency-based learning in nursing education to meet the performance requirements for entry-to-practice nurses better. Like many medical and health sciences academic programs, nursing education programs operate differently than many of higher education’s more conventional counterparts. While many didactic courses built into a nursing curriculum look similar to a typical practice in higher education, students must also participate in a significant amount of experiential learning as part of their study. Experiential learning is accomplished by pairing experiences in a clinical setting or through live or virtual simulation experiences along with didactic learning experiences. Completing these learning experiences culminates in a degree that prepares students to pass the National Council Licensure Exam (NCLEX). Passing the NCLEX gives an individual the Registered Nurse (RN) license required for practicing nurses nationwide.

Many programs have succeeded in pairing didactic and experiential learning to prepare nurses to pass licensure exams through a more traditional face-to-face modality. The ominous nursing shortage has forced educational leaders to rethink their strategies for preparing nurses for practice to accommodate the greater need in the medical field. A 2022 fact sheet produced by a leading nursing education quality assurance program, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (2022), shared that 91,938 qualified students were turned away from undergraduate and graduate programs because of a need for more resources to educate these students. Many have turned to online education to resolve the issue of insufficient resources because the medium allows more students to enroll in nursing education courses while requiring less infrastructure and personnel to support the experience than the face-to-face modality requires. Online nursing education has the infrastructure to accommodate the didactic portion of a student’s education, but best practices for online education are often not employed as courses are transitioned (Gaston & Lynch, 2019; Tiedt et al., 2021). In addition, leaders are being challenged to meet the experiential learning requirements without the appropriate means to complete these experiences at a distance and online.

Educational leaders at all levels are producing efforts to address the unique challenges and current issues faced in nursing and nursing education. In North Carolina, the legislature is proposing that state colleges and community colleges work to produce 50% more nursing graduates in the next five years (University of North Carolina System, 2023). To accomplish this goal of preparing more entry-to-practice nurses, colleges will need to introduce radical changes to their operations. In organizations already taxed by limited resources and personnel, such radical changes present vast challenges that seem nearly impossible to overcome. The leadership at a large rural North Carolina nursing college began a process to address the need to produce more nurses by meeting with several stakeholders and asking questions related to a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) assessment. For the graduates of this nursing program, the college boasts impressive licensure exam pass rates in its undergraduate and graduate programs that are routinely well above the national average. There is a strong desire to maintain the college’s remarkable outcomes while examining ways to accommodate the upcoming changes. In addition to the challenges already identified, the college has experienced a large wave of experienced faculty aging out and retiring. While this welcomes new opportunities and individuals into the organization, the experience lost through retirees reverberates through each program at the college.

The questions the college hopes to answer include:

- How does it make the best use of online instruction?

- How does it provide opportunities for faculty to improve their skills?

- How does it maintain the college’s high-quality outcomes while providing greater program access?

The first author engaged with the college to address these questions using established instructional design processes along with learning management systems technologies to address these questions.

Literature Review

A literature review seeking the best practices for online nursing education reveals significant gaps—providing little guidance for nursing education faculty. A review of peer-reviewed journal articles from the last five years in several nursing, education, and nursing education databases yielded eighty potentially relevant resources. The search utilized keywords online, nursing, and education, along with numerous variations synonymous with each term, to identify a comprehensive listing of current literature on the subject. Of the eighty potential resources identified, fifty were relevant to the research focus of online nursing education. The COVID-19 pandemic triggered significant changes in nursing education. It was a common theme in recent literature as many articles explore the pandemic's effects on instructors, students, and online education. The perception of distance learning has been increasingly negative among nursing educators since the pandemic because of the difficulties experienced in delivering education to what they felt was comparable to their face-to-face modality (Eycan & Ulupinar, 2021). There is a great need for nursing instructors to develop online courses with evidence-based practices to address the difficulties being faced (Schroeder et al., 2021).

Picciano (2017) identified three models used in online education: Community of Inquiry (CoI), Connectivism, and Online Collaborative Learning (OCL). The CoI model is intended to create meaningful and compelling learning experiences by employing three types of presence in an online course: social presence, teaching presence, and cognitive presence (Cleveland-Innes et al., 2018). While several articles alluded to the use of CoI in nursing education courses and their effects on instruction, there needed to be more indication of how nurse educators specifically applied CoI to their online courses. Connectivism and OCL were not found in any resources used in nursing education courses.

In addition to online learning models, two systematic strategies permeated the literature: discussion boards and active learning. While there were ample resources to address online nursing education in the last five years regarding the experiences and needs of nursing instructors, there is surprisingly little to no practical explanation for nursing educators to apply best practices to their courses. While there were several conclusions that nursing educators should use theory to drive the development of their courses, a significant gap exists in the practical application of allowing theory to influence practice. If educators are to heed the advice of the literature, further study and resources are needed.

The nursing college began discussions on how to implement change that addresses the vast scope of barriers facing quality nursing education. Improving online education is a large part of the college’s discussions on refining and expanding its instructional opportunities. The leadership is familiar with teaching online in programs that utilize Quality Matters (QM) for their online courses and tasked a small team of instructional leaders to implement the Quality Matters standards into the college’s online courses. The stakeholders for the initiative included the leadership team for the college, the newly formed QM team, the faculty teaching online courses, and, ultimately, the students who would benefit from course improvements.

Instructional Design Process

The project employed the ADDIE Model, a widely recognized instructional design system represented by five stages: Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation. In the Analysis stage of the project, data on the target audience, learning environment, and current instructional practices was gathered and examined. The analysis informed the construction of the project's instructional goals and intended learning outcomes. The Design and Development stages followed the Analysis stage, simultaneously involving planning assessment, learning activities, and course materials and aligning these elements to provide a streamlined instructional design. After completing Design and Development, the project progressed to the Implementation stage, where the learners engaged with the designed course. The Evaluation stage began during the Implementation stage and employed observation, discussion, and surveys to evaluate the achievement of the intended learning outcomes.

Analysis

The analysis stage reviewed resources to understand better the target audience, the instructional context, and the learner’s need for instruction. A learner and context analysis guided the best course of action on the modality for learning, learning strategies to be used, and other logistical information to successfully design the instruction. As part of these analyses, demographical information on the target audience was explored and included reviews of databases, website directories, and conversations with key academic leaders to compile a comprehensive faculty profile. A task analysis explored the gaps between the current and ideal performance environments and elements to be implemented to employ best practices for online education moving forward. Several courses from various academic levels were reviewed to provide a sampling of the college's current state of online courses. The QM standards were examined to understand the vision of the college’s leadership when they pictured an ideal setup of courses for the college. The conversations with key individuals at the college and a review of information about the learning audience, learning context, and tasks culminated in developing instructional goals and objectives for the instruction to be designed.

In surveying the faculty on their awareness and understanding of QM and the standards, approximately half needed more familiarity with QM, and only about three percent were comfortable with implementing the standards in their courses. Course design in the college is primarily unregulated, and except for curriculum objectives determined by both accrediting bodies and the university’s curriculum committee, instructors maintain academic freedom in course design. To implement the QM standards into the college’s online courses, two things would need to happen:

- The instructors would need support adapting their online courses to meet the QM standards.

- The instructors would need to be educated on the practical application of the QM standards in their online courses.

Virtually all the courses in the college’s programs use online instruction as a course delivery modality. The college has a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) program split into three subsections. Two of the subsection’s courses are primarily face-to-face, but all have online components. The third section, the RN-to-BSN program, is 100% online. The college also has a graduate program for advanced practice nursing education with a Master of Science in Nursing (MSN) and a Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP), each with concentrations and a terminal Ph.D. program. All advanced practice and Ph.D. program courses are offered entirely online. The classes are hosted on the university’s sponsored learning management system (LMS), Canvas.

Within the first three years of employment, all faculty at the college are required to either complete an academic program that leads them to pass an exam and become a Certified Nursing Educator or participate in a 45-hour professional development course designed for nurse educators. Higher education instructors are often well-prepared practitioners but may need the pedagogical training or experience required to succeed in online teaching. In a study on teacher readiness for online teaching and learning, Scherer et al. (2021) concluded that there were no consistencies in teacher readiness for online learning among the groups studied. For the North Carolina nursing college, ninety-one percent of the faculty identify as female, with 9% identifying as male. They range from approximately age 30 to age 70 and have a similar range in experience level. Five primary academic backgrounds are shared among the college’s nursing instructors: RN, BSN, MSN, DNP, and Ph.D. In addition to the nursing background, a select few have academic backgrounds in education, business, and law. The college’s faculty makeup suggests it likely reflects the study’s findings completed by Scherer et al. (2021).

An analysis of the many online courses for the college showed little consistency in design other than the default layout provided by the Canvas LMS. Students taking multiple classes must learn to navigate each course designed differently by each instructor. Faculty often report that course navigation tends to be a significant source of negative feedback in student opinion of instruction surveys. Smadi et al. (2019) found that 70% of the population of online nursing educators they studied did not use an explicit theoretical framework to guide the design of their online courses. This lack of theory guidance could be due to the great need for instructors to be trained in best practices for online education (Brown et al., 2009; Eycan & Ulupinar, 2021; Nabolsi et al., 2021; Sinacori, 2019). The study addressed the college’s need for training on the best practices for online education in course design. Using the information gathered from the analysis of the learning environment and learners and considering the standards for course design from Quality Matters, the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL), and the guidelines from the international standard of Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), the first author designed an online, asynchronous course for faculty to learn the best practices for online course organization.

The observation and analysis of many of the college’s online courses and empirical observation of learning applications and strategies identified vital issues to address in educating the faculty on online course organization.

- A well-organized course is crafted carefully with simplicity in mind. Course design should evaluate every element for its instructional purpose. Parts with no instructional purpose should be removed.

- A well-organized course is consistent. A course should employ repetitive elements in navigation, layout, and vocabulary. A learner should quickly become familiar with the course flow and where to access information.

- A well-organized course is transparent. Instructors should design their courses so that no prior experience is needed to comprehend how to engage with course content. The course design should employ standard, easily recognized interface features and familiar vocabulary to describe elements and a logical navigational flow.

An online, asynchronous course for nursing education faculty was produced to model and explain these best practices in course design.

Design & Development

During the design stage, a plan for instruction was created based on the information gained from the analyses. There were three course-level objectives to be addressed in the instruction. Upon completion of the course, learners will be able to:

- Adapt overview and introduction information to address QM standards.

- Generate clear and thorough instructions.

- Evaluate the accessibility and usability of course content.

Understanding the analysis of the learner, the course would need to be designed with the understanding that participants would likely engage at different times or in different ways. Some participants may spend a weekend and complete the course, while others may spend chunks of time throughout the two weeks allotted for course completion. So, the plan was to design content that could accommodate learners’ schedules as best as possible. In addition to the content provided in an informative manner, the course itself would need to model the performance environment so that participants of the course could experience the design from a student’s perspective—just as their students would when they adapt their course designs later.

The design considered that assessing the participants’ learning would be difficult. Required activities would likely become a burden and would likely encourage less participation. So, learning activities were designed to create opportunities for feedback from the course facilitator without requiring participation. While this is not the ideal scenario for learning, it was the appropriate step in the continuum of improvement for the college.

In conjunction with the design process, pieces of the courses were developed as part of an iterative design, development, and self-evaluation process. The design developed a course matrix that utilized backward design to align instructional materials, learning activities, and other course elements between the course objectives and the desired outcomes. This matrix informed what content would be needed for course participants to reach the desired outcomes successfully. If good content was already created and available for use, the course utilized that content without needing to “recreate the wheel.” Many videos were created to address specific topics requiring further development. The other elements of the course were carefully crafted to model the best practices for online course design according to the QM standards and the content taught in the course.

The completed course features a simple home page that is the first item learners see when logging in to the course (see Figure 1). Here, learners can play a short welcome video that, beyond its practical purpose of welcoming learners, is an example of employing the Community of Inquiry online learning framework for the course. There were intentionally no synchronous sessions scheduled for this course that would typically introduce an instructor. Instead, the first introduction to the instructor is made through a welcome video that begins to provide a teaching presence in the course. Simonsen et al. (2019) describe one of the fundamental elements of distance learning to be the separation between the instructor and learner; the concepts of teaching presence and social presence in the Community of Inquiry framework support an increase in student engagement and ultimately more successful learning outcomes (Thompson et al., 2020). The course intentionally provides multiple opportunities for the learner to see and hear the instructor as an organizational technique and pedagogical model for participants.

Figure 1. Sample home page with a welcome video, instructor contact information, and navigation buttons.

Another organizational feature of the course is providing course and module overviews. The course overview includes course objectives in a prominent location as required by QM standards and serves as a tour guide. The module overviews (see Figure 2) serve the same function for individual modules. In each overview, learners may view a video that guides them through the expectations for module participation designed to create a more transparent learning experience. Each overview has a “to-do/tasks to complete” list to provide a clear message of the consumable content for learners and the expected deliverable assignments. Each overview is designed to present the learner with knowledge of everything necessary for success in that portion of the course.

Figure 2. Sample module overview page with objectives, overview video, and to-do list.

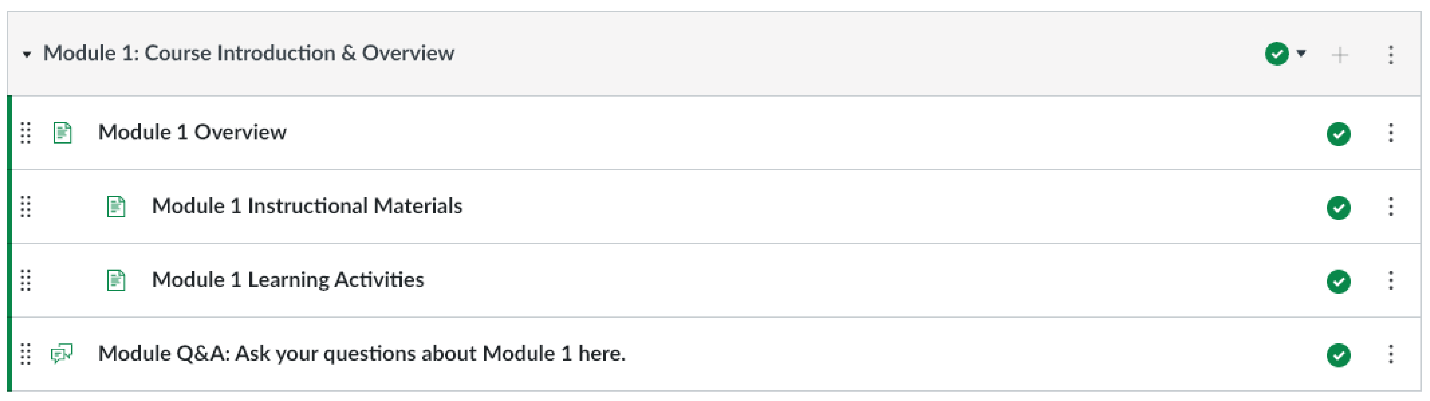

The last of the significant design elements that model online course organization is the intentional consistency of the course modules (see Figure 3). There is a “Start Here” module that some call “Module 0” that consists of introductory content and activities and is modeled closely to the main modules of the course. There were two content modules, each designed to last one week, consisting of a Module Overview, an Instructional Materials page, a Learning Activities page, and a Q&A discussion board. The Instructional Materials page includes all consumable course content for the learner. All consumable course content (video, article, presentation, etc.) is embedded or linked in a recommended order of completion. Similarly, the Learning Activities page contains all content considered a student assignment. Again, this is listed in a suggested order of completion. On both pages, each element includes a statement just below the content stating how the element helps the learner achieve specific or multiple module learning objectives. Not only is this a standard for QM, but it is also a way to be transparent with the course’s purpose for students consistently throughout the course.

Figure 3. Sample module layout.

Implementation

Sign-up for the course was offered to all faculty of the college, even part-time and adjunct instructors. Instead of traditional training opportunities at the college that were offered synchronously at a time that may or may not be convenient for the participants, this course was offered for two weeks asynchronously. It was recommended that learners complete the content of one module per week, including instructional materials and learning activities.

Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted with approval from the Institutional Research Board (IRB), and each participant could provide or not provide their data for research purposes by signing a consent form. Any identifying information of participants has been removed to protect their privacy.

Evaluation

A survey that employed an objectives-based and goal-free evaluation approach (Giancola, 2021) was conducted among those who completed the course during its effectiveness assessment period. The course included eleven participants, and five contributed to the evaluation results. The evaluation tool used a quantitative Likert scale with five options (1- Disagree, 5- Agree) to evaluate whether the course objectives were met from participation in the course. In addition to the objectives, there were three questions to assess if the instruction was accessible, credible, and engaging based on the second author’s A.C.E.S. accessible, credible, engaging, and secure model (Brown, 2022) for determining effective online instruction. Furthermore, the three qualitative questions were open-ended, allowing for feedback not considered in the objective-based questions. These questions ask what the instruction should have spent more time on, less time on, and any other feedback that participants would like to provide. Overall, the feedback was remarkably positive, but there were a few things to note.

First, there was much praise for the content created for the course. Participants commented, “[The course] really was great and a very efficient use of time” and, “I think the course is very well weighted on content.” There were multiple participants in the course who had indicated prior experience in taking QM courses. However, this course provided practical instruction on implementing these practices into their online courses. One participant even shared the desire for this content to be offered to all faculty, especially faculty new to online learning. The course provides tips and explanations of skills that almost every online instructor will encounter but are rarely covered at the theoretical level that most academic courses offer.

The course's most significant observation and evaluation was possibly related to active and passive learning. This was a polarizing issue for the course. One participant noted they “…felt like there were a lot of videos.” Liu et al. (2021) advocate for online instructors to consider active learning strategies for student satisfaction and successful student learning outcomes. Current literature on online education almost unanimously agrees on the importance of active learning strategies in online learning. Consequently, this idea is polarizing because the course almost exclusively includes passive learning opportunities. This was intentional based on the initial analysis. For many instructors with full workloads, there is little time to engage in professional development opportunities within their work schedule. As a result, they use their personal time for professional growth. Also, considering an instructor’s busy schedule, passive learning activities do not require the same amount of attention as active learning activities and allow them to engage as participants in professional development opportunities in convenient chunks of time. Further experiments with course design may help determine the best balance between active and passive course activities for maximum effectiveness and information retention.

There were two other suggestions drawn from the evaluation tool for improvement. First, the consumable content consisted of many videos. While the quality and scope of the videos were praised, as noted, comments were made about the large number of videos. The type of content should have been more diverse against the best practices highlighted in the QM standards. In addition, there was a desire for more procedural content to be included in the course as one participant desired “more ‘how-to’ information,” such as navigating and completing some of the tasks mentioned in the videos in Canvas.

Recommendations

Considering realistic changes to improve the effectiveness of the course, the first consideration must be shifting to active learning strategies to some measure. The key will be balancing the data gathered from the analysis, the idea of active strategies, and the time and effort required for participants. Nevertheless, Son and Park (2021) emphasize that nursing instructors should prepare their courses with appropriate active learning strategies to increase students' learning outcomes. If this course, designed to train nursing educators, is to model the best practices for course design, then it will need to follow best practices in its design and employ active learning strategies. The challenge is in finding the ideal balance. Practically, not every activity needs to engage an active learning strategy. However, in alignment with the course objectives, each objective should have active learning strategies so participants are not merely consumers of information but constructors of knowledge.

An important consideration pertains to the limitation presented by the project’s relatively small sample size. The instructional evaluation could have benefitted from a larger sample size for maximum reliability from the feedback provided. A larger sample size would likely have provided more diverse feedback and better insight into how this instruction could be applied to various learning environments. Further iterations of this course should consider employing larger and more diverse sample sizes to provide feedback reliability and make more informed decisions.

Another vital consideration for improving the course is varying content. Just as principles of accessibility are taught in the course, varying the types of content ensures that efforts are made to meet all learners. Simply put, all learners do not learn from information presented passively in a video. Different learning styles should be considered, and content should attempt to address objectives from multiple vantage points to meet the diverse needs of learners in an online environment.

Discussion

After completing the course Online Course Organization, conversations on course design at every college level are beginning to happen. The course's best practices were presented to the faculty in a series of meetings with leadership and faculty in the Advanced Practice Nursing Education department that facilitates nearly all the college's graduate-level education. In an unprecedented decision, the faculty unanimously agreed to implement an online course template for the upcoming semester based on the best practices presented in the Online Course Organization course. Faculty not only decided to move forward with redesigning their courses to meet the needs of students, but many faculty were eager to begin improving the college’s online courses to benefit student success. While the course aims to provide professional development to instructors needing support, it began to facilitate change in the culture of the college. Instructors are now designing with best practices and the learner in mind collaboratively with other instructors. While the shift is beginning, it has produced much excitement for the department and college courses’ future. Implementing QM standards into the nursing college’s courses has already started a process of positively transforming courses and instructors. The QM standards represent many best practices for designing online courses, highlighting the instructional design process of backward design, writing clear and measurable objectives, creating content that is accessible to all learners, and organizing a student-centric course.

The first QM standard for higher education addresses the need to be clear about where students should start. The recommendation is to have a link on the first page visited with the phrasing “Start here.” With the overwhelming challenges in nursing education and the many attempts to address the challenges, for this large rural North Carolina college, the Online Course Organization course has served as a “Start here” button in addressing the challenges in educating nurses.

The Online Course Organization course has served as a catalyst for many course improvements. While the sample size is relatively small, the approach has impacted many instructors, even those not participating in the course, to consider evidence-based practices for their online courses. Specifically, instructors have begun to understand the significance of teaching presence in their courses and have increased their presence by adding welcome and module overview videos. One instructor redesigned their summer course to reflect QM standards for course organization and accessibility. The instructor reported receiving highly positive feedback from a student on the first day of their course, stating, “These changes have made your courses the easiest to navigate out of any courses I have been in.” By addressing course design and diverting attention from course content, nurse educators have welcomed feedback and changes to their courses without threatening their expertise in nursing.

It is essential to understand that the change that the North Carolina college is experiencing happens on a continuum. The Online Course Organization course served as a much-needed intervention. However, the resulting ideas of a template should be seen as a starting point rather than the goal. In The McDonaldization of Society, George Ritzer (2020) discusses the rationalization of processes in our society, like the fast-food chain McDonald’s. While rationalizations produce consistency and expediency, they do not always correlate with quality. Just as one would likely not substitute an innovative and impressive meal from a Michelin-star restaurant with a consistent and expedient meal from McDonald’s, our online courses should not substitute innovation for rationalization. The template should serve as a scaffold to unify an educational program and promote best practices for instructional design in their online courses. However, the course template should be a starting point, not an end. Ideally, faculty develop the experience and sophistication necessary to explore their instructional practice further, innovating and improving their course designs beyond the templates that provide initial support.

As Boling (2010) observes, a “design case is a description of a real artifact or experience that has been intentionally designed,” documenting a precedent that may serve to inspire similar work. Hopefully, this design case provides ideas for further design experiments in both online instruction and nursing education. Nursing educators must effectively pair evidence-based clinical practices with evidence-based instructional practices to address the significant challenges in a post-pandemic educational environment, a major curriculum change, and resolving an overwhelming nursing shortage. With significant gaps in research on best practices for online nursing education, the intersection between traditional instructional design and online nursing education is fertile ground for further research.

Acknowledgment: This study was completed in partial fulfillment of the first author’s completion of the Master of Science in Instructional Technology degree program at East Carolina University.

References

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2022). Nursing Faculty Shortage [Fact Sheet]. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Fact-Sheets/Faculty-Shortage-Factsheet.pdf

Brown, A. (2022). A.C.E.S. explained [Online course presentation]. In A. Brown, Instructional strategies for distance learning. East Carolina University. Greenville, NC. September 2022.

Brown, S. T., Kirkpatrick, M. K., Greer, A., Matthias, A. D., & Swanson, M. S. (2009). The use of innovative pedagogies in nursing education: an international perspective. Nursing education perspectives, 30(3), 153–158.

Boling, E. (2010). The Need for Design Cases: Disseminating Design Knowledge. International Journal of Designs for Learning, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.14434/ijdl.v1i1.919

Cleveland-Innes, M., Garrison, D. R., & Vaughan, N. (2018). The Community of Inquiry Theoretical Framework. In W.C. Diehl & M.G. Moore (Ed.) Handbook of Distance Education (4th Edition, pp. 67–78). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315296135

Eycan, Ö., & Ulupinar, S. (2021). Nurse instructors' perception towards distance education during the pandemic. Nurse Education Today, 107, 105102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.105102

Gaston, T., & Lynch, S. (2019). Does using a course design framework better engage our online nursing students? Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 14(1), 69–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2018.11.001

Giancola, S. P. (2021). Program evaluation: Embedding evaluation into program design and development. SAGE.

Howe, D. L., Chen, H.-C., Heitner, K. L., & Morgan, S. A. (2018). Differences in nursing faculty satisfaction teaching online: A comparative descriptive study. Journal of Nursing Education, 57(9), 536–543. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20180815-05

Little, B. B. (2009). Quality Assurance for online nursing courses. Journal of Nursing Education, 48(7), 381–387. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20090615-05

London, J. (2018). Use of asynchronous audio feedback in discussion boards with online RN-BSN students. Nurse Educator, 44(6), 308–311. https://doi.org/10.1097/nne.0000000000000633

Nabolsi, M., Abu-Moghli, F., Khalaf, I., Zumot, A., & Suliman, W. (2021). Nursing faculty experience with online distance education during COVID-19 crisis: A qualitative study. Journal of Professional Nursing, 37(5), 828–835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2021.06.002

Picciano, A. G. (2017). Theories and frameworks for online education: seeking an integrated model. Online Learning, 21(3). https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v21i3.1225

Quality Matters Rubrics & Standards. Quality matters. (n.d.). Retrieved February 1, 2023, from https://www.qualitymatters.org/qa-resources/rubric-standards

Regmi, K., & Jones, L. (2020). A systematic review of the factors – enablers and barriers – affecting e-learning in health sciences education. BMC Medical Education, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02007-6

Ritzer, G. (2020). The McDonaldization of society: Into the digital age, 10th ed. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

Scherer, R., Howard, S. K., Tondeur, J., & Siddiq, F. (2021). Profiling teachers' readiness for online teaching and learning in higher education: Who's ready? Computers in Human Behavior, 118, 106675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106675

Simonson, M. R., Smaldino, S. E., & Zvacek, S. (2019). Teaching and learning at a distance: Foundations of Distance Education. Information Age Publishing, Inc.

Sinacori, B. C. (2019). How nurse educators perceive the transition from the traditional classroom to the online environment: A qualitative inquiry. Nursing Education Perspectives, 41(1), 16–19. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nep.0000000000000490

Smadi, O., Parker, S., Gillham, D., & Müller, A. (2019). The applicability of community of inquiry framework to Online Nursing Education: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Education in Practice, 34, 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2018.10.003

Song, C. E., & Park, H. (2021). Active learning in E-learning programs for evidence-based nursing in academic settings: A scoping review. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 52(9), 407–412. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20210804-05

Tiedt, J. A., Owens, J. M., & Boysen, S. (2021). The effects of online course duration on graduate nurse educator student engagement in the community of inquiry. Nurse Education in Practice, 55, 103164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103164

Thompson, C. E., Ahern, N., & Crawford, S. (2020). Practical guidelines to use Facebook as an alternative to discussion boards for online RN-BSN students. Nurse Educator, 45(5), 239–240. https://doi.org/10.1097/nne.0000000000000774

University of North Carolina System. (2023) Recommendations on Increasing Nursing Graduates: In Response to SL 2022-74 (HB 103), Section 8.3. NCCommunityColleges.edu. https://www.nccommunitycolleges.edu/sites/default/files/state-board/program/prog_03_-_recommendations_on_increasing_nursing_graduates_in_response_to_sl_2022-74_hb_103_section_8.3.pdf