Abstract

As faculty continue to focus on creating supportive learning environments for students, both on campus and online, it is essential to analyze the sense of belonging and how it is intentionally nurtured in our educational settings. With the expansion of online enrollment and the changing landscape of in-person classrooms, understanding students' sense of belonging and their relationships with faculty, peers, and their learning environment becomes crucial.

Our study utilized scaled questions adapted from the belonging survey developed by Hoffman et al. (2002-2003). Item responses were measured using a Likert scale, where 1 represented the lowest score/value and 5 represented the highest score/value. All actively enrolled university students were invited to complete an anonymous survey.

This study investigates how undergraduate students at a public 4-year university experience a sense of belonging in both in-person and online learning environments. It focuses on the influence of faculty-student interactions, peer connections, and classroom support on students’ perceptions of inclusion and connectedness. This research seeks to inform the development of inclusive pedagogical and institutional strategies that foster belonging across all learning modalities. Ultimately, the study aims to support the creation of equitable, affirming educational environments in which all students, regardless of modality, can thrive.

The results indicate that online students experience an increased sense of belonging when they perceive greater faculty support and classroom support. This raises questions about whether their sense of belonging is influenced more by the design of the online platform compared to traditional face-to-face classroom settings as well as implications for increasing perceived peer support/interactions. For on campus students, perceived peer support ranks as a more critical factor to developing a sense of belonging, with perceived faculty and classroom support ranking as needed in some areas, but not in others. Our results suggest the differences between online students and on campus students' sense of belonging comes from different layers of support. Implications for institutions are numerous with a focus on increased opportunities for faculty interactions, and engaging students in the virtual and in-person classroom environment.

Keywords: sense of belonging; online learning; higher education; perceived support - peer, faculty, classroom

Introduction

A sense of belonging is a fundamental human need (Maslow, 1958). Belongingness—the perception of being accepted, valued, and connected within a learning community—is integral to the academic experience and has been consistently linked to a range of positive outcomes. Research indicates that students who feel a sense of belonging tend to achieve higher grades, exhibit increased retention rates, demonstrate persistence toward degree completion, and experience enhanced psychological well-being (Allen & Bowles, 2013; Pedler et al., 2022; Strayhorn, 2019; Walton & Cohen, 2011).

According to Belongingness Theory, humans have an innate need to belong with other individuals and groups, and when this need is not met, we face significant socioemotional, relational, and developmental challenges (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Maslow, 1958). This concept is especially significant for students who face systemic barriers related to race, class, geography, sexual orientation, gender identity, disabilities, or first-generation college status. Institutions that serve large populations of first-generation, low-income, and historically marginalized students must be especially attentive to how belonging is cultivated across all dimensions of the student experience. These institutions must develop intentional strategies that enhance students' feelings of connection and acceptance, including academic/faculty support, classroom/learning environment, and social/peer interactions (Allen et al., 2016).

Social Presence Theory highlights the learner's skill in engaging interpersonally with other people regardless of environment in a community of inquiry (Garrison, 2017). Zhan and Mei (2013) noted that this ability to be socially present hinges on the perception of an individual's relationships with others, faculty, and peers, rather than how they feel about themselves as a learner. Engagement-focused behaviors, such as initiating conversations with peers about assignments or sharing personal experiences, have been shown to foster connections and build a sense of camaraderie among students (Alotaibi et al., 2023). However, past research has demonstrated that students enrolled in online classes often report feelings of isolation and disconnection from their peers (Farrell & Brunton, 2020). These findings underscore the importance of creating structured opportunities for interaction, whether through virtual platforms or in-person gatherings, to help bridge the gap and promote collaborative learning. By prioritizing initiatives that enhance belongingness, educational institutions can significantly contribute to the overall success and well-being of their diverse student populations, a key predictor of student success in higher education (Burgin & Munasinghe, 2024).

Online Education and Connection

Online courses and programs in Higher Education increased during and post-COVID, with many students continuing to seek out online degrees (Garrett et al., 2023). In 2019, 15% of undergraduates enrolled in online programs, and this increased to 28% by 2021 (NCES, 2023). We continue to see a growing number of online undergraduate and graduate degree programs at universities (Garrett et al., 2023).

An increasing body of evidence suggests online education may negatively affect a student's sense of connection, resulting in feelings of isolation, loneliness, and disempowerment (Bickle et al., 2019; Kaufmann & Vallade, 2022; Ragusa & Crampton, 2018; Roddy et al., 2017; Rose, 2017). Thus, while online learning offers educational advantages such as flexibility and accessibility, it could also lead to educational disadvantages (Burke & Larmar, 2020). Research points out peer-to-peer interactions are crucial for increasing students’ belongingness, which facilitates positive outcomes (Sandstrom & Rawn, 2015).

In today’s educational landscape, where learning often occurs across both physical and digital platforms, fostering belonging presents new challenges and opportunities. Online learning environments offer greater flexibility and access but can also heighten experiences of isolation and invisibility, particularly for students whose identities are underrepresented or misunderstood in virtual settings (Garrison, 2007). Meanwhile, on-campus experiences can vary widely depending on students’ access to inclusive resources, social networks, and perceptions of institutional care and support.

Two consistent themes in the literature emerge as critical to fostering belonging: faculty engagement and peer support (Zhao & You, 2024). Faculty who intentionally create inclusive, responsive, and affirming learning environments, whether in person or online, play a central role in helping students feel seen, respected, and valued. Likewise, positive peer relationships provide emotional support, foster resilience, and strengthen students' sense of community within the institution (Strayhorn, 2019).

This study investigates how undergraduate students at a public 4-year university experience a sense of belonging in both in-person and online learning environments. It focuses on the influence of faculty-student interactions, peer connections, and classroom support on students’ perceptions of inclusion and connectedness. This research seeks to inform the development of inclusive pedagogical and institutional strategies that foster belonging across all learning modalities. Ultimately, the study aims to support the creation of equitable, affirming educational environments in which all students, regardless of modality, can thrive.

Methods

Research Question

For this study, the researchers hypothesized that a sense of belonging would be built upon relationships with peers and faculty. We also hypothesized that students in campus programs would feel a stronger sense of belonging compared to the online students. The final hypothesis was that stronger faculty relationships would be associated with a sense of belonging among students.

Study Design

This research study employed an anonymous quantitative survey design, approved under expedited review by the IRB #6121. Students were eligible if they were currently enrolled university students aged 18 and older with a university email address. The survey was distributed via the official university email system, ensuring voluntary and anonymous participation. The survey was accessed through a QR code or link, and data security was maintained using Qualtrics software, which limited responses to one per participant and anonymized data by removing IP addresses. The survey was accompanied by a research study description with implied consent by clicking “Next” and completing the survey.

Survey data were collected between November 2024 to February 2025, with semi-monthly email reminders following the initial invite to encourage participation during the data collection period. The survey used questions from Hoffman et al.’s Sense of Belonging scale (2002-2003). Each question included Likert scale response options from 1 Strongly Disagree to 5 Strongly Agree. Categories included questions on the respondent’s perception of peer support, classroom support, and faculty support.

Results

A total of 918 unique responses were received, of which 758 were identified as fully completed. Table 1 provides demographic information for these 758 responses, including details on academic programs, gender identity, employment status, and age group.

Participant Characteristics

Responses were grouped according to program type - campus students (n=381) or online students (n=374). Among online students, 24% identified as male, 72% as female, and 3% as non-binary or transgender. For on-campus students, the breakdown was 29% male, 63% female, and 3% non-binary or transgender. Notably, 85% of on-campus student respondents were aged 18-24, significantly younger than online students, while over 50% of online student responses came from two age groups: 34% were aged 35-44, and 20% were aged 45-54.

Examining employment status data reflected significant differences between online and on-campus students regarding full-time employment: 55% of online students reported working full-time, compared to only 8% of on-campus students. However, part-time and student status rates were notably high among on-campus students, with 37% working part-time and 46% responding as “student” as their current vocation.

Students reported their area of study on the survey. Fifty-five percent of online students were Humanities and Social Science majors, 10.1% were STEM and Business majors, and 33.1% were Health Sciences and Safety majors. Over one-third (37.8%) of campus respondents were STEM and Business majors, and 34.6% were Humanities and Social Science majors.

Table 1. Participant Characteristics Comparing Online (n=381) with Campus (n=374) Students

| Characteristics | Online % (n) | Campus % (n) |

| Age group *** | ||

| Under 18 | 3.1% (12) | 1.6% (6) |

| 18-24 years old | 17.5% (67) | 84.5% (316) |

| 25-34 years old | 17.5% (67) | 5.3% (20) |

| 35-44 years old | 34.3% (131) | 4.0% (15) |

| 45-54 years old | 20.4% (78) | 2.1% (8) |

| 55-64 years old | 5.5% (21) | 2.4% (9) |

| 65+ years old | 1.6% (6) | — |

| Gender Identity* | ||

| Male | 23.7% (90) | 29.1% (109) |

| Female | 72.3% (274) | 63.1% (235) |

| Non-binary /transgender | 2.6% (10) | 3.2% (12) |

| Prefer not to say | 1.3% (5) | 4.5% (17) |

| Employment Status *** | ||

| Full-time | 55.2% (211) | 8.3% (31) |

| Part-time | 11.3% (43) | 36.9% (139) |

| Unemployed/Looking | 2.9% (11) | 7.0% (26) |

| Stay-at-home parent | 5.8% (22) | 0.5% (2) |

| Student | 19.9% (76) | 46.3% (173) |

| Retired/other | 5.0% (19) | 1.1% (4) |

| Area of Study*** | ||

| Humanities and Social Sciences | 56.8% (213) | 34.6% (129) |

| STEM and Business | 10.1% (38) | 37.8% (141) |

| Health Sciences and Safety | 33.1% (124) | 27.6% (103) |

Perceived Student/Peer Support Ratings

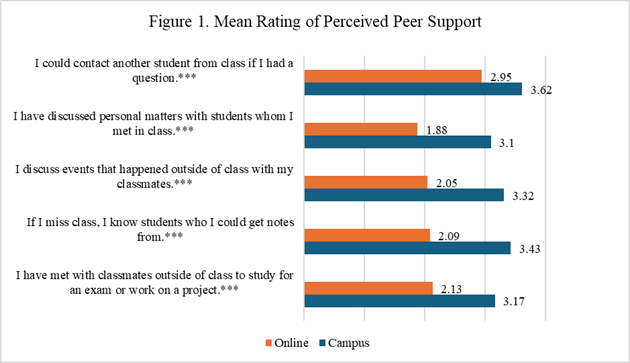

In Figure 1, mean ratings of student perceived support are displayed, comparing online and campus student responses. All statements included in-person and/or virtual contacts per the survey instructions. Students were asked to rate statements about peer support using the Likert scale ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”. Students in the campus group had significantly higher perceived support ratings for every statement. Campus students felt they could contact other students for help to discuss classwork, ask for notes, meet about a project or to study for an exam, or talk about personal matters.

***p=<.001

Perceived Classroom Support Ratings

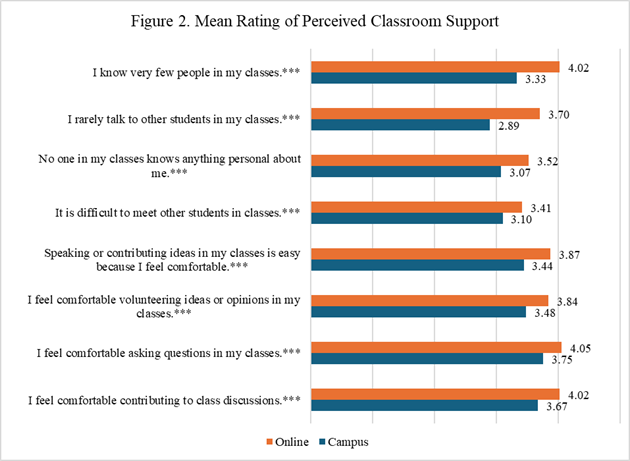

In Figure 2, ratings of perceived classroom support are displayed. Using the same Likert scale ranging from 1 (low) to 5 (high), students rated their perception of classroom support. Comparing student responses, the data highlights less engagement and support felt in the classroom by online students. They reported being more comfortable than campus students asking questions in class, speaking or contributing to class discussion, or volunteering ideas or opinions. More online students responded they rarely talked to other students in classes, knew few of their classmates, and felt like it was difficult to get to know other students.

***p=<.001

To provide more detail, in Table 2 one-way ANOVA results are displayed for Figures 1 and 2.

Table 2. Differences Among Online and Campus Responses in Perceived Peer and Classroom Support - One-way ANOVA

| Perceived Peer Support Statements | Online Mean | Campus Mean | F | df | p |

| I have met with classmates outside of class to study for an exam or work on a project. | 2.13 | 3.17 | 91.03 | 1, 754 | <.001 |

| If I miss class, I know students who I could get notes from. | 2.09 | 3.43 | 178.53 | 1, 752 | <.001 |

| I discuss events that happened outside of class with my classmates. | 2.05 | 3.32 | 161.05 | 1, 754 | <.001 |

| I have discussed personal matters with students whom I met in class. | 1.88 | 3.10 | 144.18 | 1, 752 | <.001 |

| I could contact another student from class if I had a question. | 2.95 | 3.62 | 41.02 | 1, 754 | <.001 |

| Other students are helpful in reminding me when assignments are due or when tests are approaching. | 2.13 | 2.99 | 76.61 | 1, 754 | <.001 |

| I have developed personal relationships with other students in classes (virtual or in-person). | 2.09 | 3.42 | 172.63 | 1, 751 | <.001 |

| I invite people I know from classes to do things socially. | 1.68 | 2.88 | 148.84 | 1, 754 | <.001 |

| Classroom Support Statements | Online Mean | Campus Mean | F | df | p |

| I feel comfortable contributing to class discussions. | 4.02 | 3.67 | 16.05 | 1, 728 | <.001 |

| I feel comfortable asking questions in my classes. | 4.05 | 3.75 | 12.18 | 1, 728 | <.001 |

| I feel comfortable volunteering ideas or opinions in my classes. | 3.84 | 3.48 | 15.96 | 1, 727 | <.001 |

| Speaking or contributing ideas in my classes is easy because I feel comfortable. | 3.87 | 3.44 | 21.93 | 1, 727 | <.001 |

| It is difficult to meet other students in classes. | 3.41 | 3.10 | 11.07 | 1, 707 | <.001 |

| No one in my classes knows anything personal about me. | 3.52 | 3.07 | 19.91 | 1, 707 | <.001 |

| I rarely talk to other students in my classes. | 3.70 | 2.89 | 60.91 | 1, 706 | <.001 |

Perceived Faculty Support Ratings

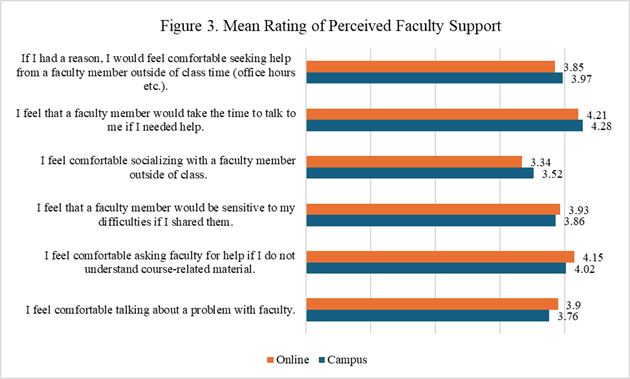

There was no statistically significant difference in perceived faculty support between online and campus students. In Figure 3, the student perception of faculty support is displayed using the 5-point Likert scale. Students in online and campus programs rated their comfort level with faculty very high. There were no significant differences between the groups in their perception of faculty support.

Employment Impact on Sense of Belonging

Examination of initial t-tests indicated that campus students who did not work while taking classes (M = 3.09, SD = 1.52) or who worked part-time (M = 3.9, SD = 1) were more likely than full-time working students (M = 2.39, SD = 1.51) to discuss personal matters with other students in class (p = .012). Mean belongingness ratings were compared by employment status using one-way ANOVA for each group – online or campus students.

Online Students, Belongingness Ratings, and Employment Status

Online students who reported working full-time while taking classes were less likely to engage with other students in their courses on a variety of levels. Significantly fewer online students who worked full-time connected with classmates outside of class to study, to discuss events or personal matters, or to meet socially, as shown in Table 3. Classroom support ratings were lowest for part-time workers who were less comfortable asking questions or engaging than peers who worked full-time or did not work while taking classes. Comparing online students’ perception of faculty support, no differences were found by employment status.

Table 3. Online Students Mean Belongingness Ratings by Employment Status – One-way ANOVA

| Peer Support Ratings | Full-time | Part-time | None | F | df | p |

| I have met with classmates outside of class to study for an exam or work on a project. | 1.96 | 2.33 | 2.36 | 3.55 | 2, 379 | .030 |

| I discuss events that happened outside of class with my classmates. | 1.86 | 2.40 | 2.23 | 5.01 | 2, 397 | .007 |

| I have discussed personal matters with students whom I met in class. | 1.71 | 2.21 | 2.05 | 4.60 | 2, 377 | .011 |

| I have developed personal relationships with other students in class. | 1.91 | 2.35 | 2.29 | 4.21 | 2, 378 | .015 |

| I invite people I know from classes to do things socially. | 1.53 | 1.93 | 1.84 | 4.04 | 2, 379 | .018 |

| Classroom Support Ratings | ||||||

| I feel comfortable asking questions in my classes. | 4.07 | 3.55 | 4.17 | 5.13 | 2, 374 | .006 |

| Speaking or contributing ideas in my classes is easy because I feel comfortable. | 3.96 | 3.46 | 3.84 | 3.18 | 2, 373 | .043 |

| I rarely talk to other students in my classes. | 3.86 | 3.44 | 3.50 | 3.92 | 2, 365 | .021 |

Campus Students, Belongingness Ratings, and Employment Status

Almost all the responses on the belongingness scales for campus students were similar when comparing employment status. The only statistically significant difference was that fewer full-time working campus students (M = 2.39) had ever discussed personal matters with students they met in class compared to part-time (M = 3.28) or non-working students (M = 3.09), [F (2, 371) = 4.46, (p = .012)].

Narrative Responses

Qualitative data were reviewed, and any responses that were “n/a” or nonsensical were removed from the analysis group. Themes are summarized below with examples from the narrative following each theme.

Desire for Involvement: There’s a clear divide. About half the students want more ways to connect and be involved, especially online. They’re looking for opportunities to build relationships, join events, or just feel more included. The other half, though, are content with minimal involvement. They prefer to focus on coursework and value the flexibility and independence that online learning offers. Some even said they don’t feel the need to make friends or build relationships through the program.

Online Connection Challenges: Many students mentioned feeling isolated in online classes. They suggested things like regular virtual meetings, cohort groups, or online social events to help bridge the gap.

Faculty Support and Communication: A lot of feedback centered on the importance of timely and supportive communication from faculty. Students appreciate when professors are responsive and proactive.

Peer Interaction and Community: Students want more chances to interact with each other, whether that’s through group work, clubs, or informal gatherings-both online and on campus.

Inclusivity and Representation: Some students noted that more inclusive practices, both in the classroom and in extracurriculars, would help them feel like they belong.

Discussion

In terms of college, sense of belonging refers to students perceived social support, a feeling or sensation of connectedness, and the experience of mattering or feeling cared about, accepted, respected, valued by, and important to the campus community or others such as faculty, staff, and peers (Strayhorn, 2019). This study aimed to understand the factors that support a student’s sense of belonging among their program type to include online programs, in-person programs, and programs housed at extended campus sites and as measured by perceived student/peer, classroom, and faculty support. Students’ perceptions of belonging can have an impact on their academic success, co-curricular engagement, mental health and well-being, and personal development (Gopalan & Brady 2020; Maghsoodi et al., 2023; Thomas 2012). Significant differences did not emerge across different academic programs or gender groups. There were differences between students who worked full-time while taking courses. Our findings suggest that students' sense of belonging is complex and can be better understood across three domains.

Perceived Student/Peer Support

The findings revealed that online students have fewer interactions with their peers than campus students. The results of our study indicated that more than half, and even as high as 70%, of the online students disagreed with the statements that specifically addressed the more positive aspects of student/peer support. Conversely, between 20% to 30% of campus students disagreed with those statements. Online peer support was lower among students who worked full-time jobs while taking classes. This perhaps indicates less available time to engage with their peers and get to know others in their class.

Perceived Faculty Support

Students were also asked to rate statements about their interactions with faculty. The majority of students reported positive experiences with faculty engagement in their classes in both online and in-person programs. The survey showed nearly equal perceived faculty support from online and in-person students. Previous research reveals that perceived faculty support correlates more with belongingness than peer support. In Hansen-Brown et.al (2022), a Hoteling’s t-test showed that belongingness was more strongly correlated with professor interaction than student interaction. Thus, although interacting with peers in remote online classes matters, it seems that interacting with professors matters more for belonging. In this sample of students, faculty appear to be engaging students in both programs equally well.

Perceived Classroom Support

The perceived classroom support data reveal some interesting patterns. While 72% of online students and 53% of in-person students agree “they know very few people in their classes,” and 59% of online students and 39% of in-person students agree “they rarely talk to other students in their classes,” the data show perceived classroom support to be high overall. Data shows that when asked about their comfort level in sharing ideas or opinions in their classes, respondents indicated they were comfortable (69% online, and 58% campus). Our data revealed that students feel comfortable contributing to class discussions and asking questions in class (76% online, 67% in-person, and 76% online, 68% in-person, respectively). Interestingly, classroom support was lower for students who worked part-time (feeling comfortable asking questions, contributing, or talking to other students). The full-time workers and those who were not working a job while taking classes had significantly higher classroom support ratings. At present, it is unclear whether students' sense of belonging is generated primarily through academic activity or through interpersonal interactions.

Implications

In terms of implications, our data suggests that institutions should focus on opportunities for students to connect with peers and faculty. This may include fostering more faculty-student relationships and opportunities for students to offer feedback and ask meaningful questions within the courses they are enrolled in. Activities like group projects and group discussions should be included in the curriculum. The demonstration of belonging with peers may be harder to achieve in an online learning environment. Online learners tend to have existing social communities through family, friends, coworkers, etc. These learners may not be looking for belonging in the same ways that the more traditional in-person student is seeking. More than wanting to connect with peers, online students want to connect with the faculty who support them (Chen, 2024).

The narrative responses provided additional implications for belonging. The 50/50 split in preferences for involvement is important. It suggests we need flexible options for students who want to engage more, while also respecting those who prefer to keep their distance. Many of the suggestions are actionable and could be implemented without much extra effort-like virtual meetups or clearer communication guidelines for faculty. The feedback gives us a good sense of what’s working and where students feel disconnected, especially in online programs.

Future research from this study will include student focus groups to better understand and garner measurement of social and relational capital as an important dimension of university belonging linked to faculty and peer relationships.

Conclusion

Belonging is a fundamental human need that serves as a key motivation for individuals. At its core, the desire to belong drives people to form relationships and connections with those around them. To truly belong is to experience a deep sense of support and acceptance in one’s environment, whether that be in a learning environment, workplace, or community. This concept can often feel abstract and may be defined and measured in various ways. For example, students may develop a general sense of belonging to their educational institution, or they may find a more specific sense of belonging within a particular course where their interests align with the subject matter. Furthermore, belonging can manifest through bonds with peers or faculty. In all these forms, belonging is communicated through the student’s perception of being accepted and connected to the group or environment they are part of. This connection can significantly influence students' motivation, engagement, and overall well-being. In traditional, in-person learning environments, peer belonging is often more easily cultivated. The ability to see peers and classmates face-to-face allows for spontaneous interactions and the creation of friendships, while physical spaces encourage social connectedness and collaboration among students. In online environments, perceived peer support seems less important, yet faculty and classroom support remain crucial to the sense of belonging. Overall, a strong sense of belonging can enhance the educational experience, leading to improved academic outcomes and personal fulfillment. Our research can help institutions of higher learning to understand student experiences within online learning and in-person learning as it relates to belonging. Our research is a significant contribution to the body of knowledge about the sense of belonging, particularly within an online environment as those learners may place value on perceived layers of support differently than their in-person peers.

Limitations of Study

While this study provides valuable insights into the experiences of belonging among undergraduate students at a regional state university, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the research is context-specific, focusing solely on the researcher's institution, a regional public institution with a distinctive demographic profile. Therefore, findings may not be generalizable to institutions with different geographic, cultural, or structural characteristics. The study relies primarily on self-reported data, which may be influenced by recall inaccuracies, personal bias, or social desirability effects. Although qualitative data offers depth, it also limits the ability to establish causal relationships or broad generalizations. Despite targeted recruitment efforts, there was limited interest in participating in focus groups. The absence of focus group data may limit opportunities for participants to build upon each other's perspectives or collectively articulate community-level insights. Participation in the study was voluntary, introducing the possibility of selection bias. Students who chose to participate may have had particularly strong feelings—either positive or negative—about their experiences, which could skew findings. The research captures data at a single point in time. Given that a student’s sense of belonging can evolve over the course of their academic journey, a longitudinal design would be better suited to explore these shifts. Finally, while the study considers both in-person and online learning environments, the variability in students' access to technology, quality of digital instruction, and individual course design may have influenced their experiences in ways that were beyond the scope of this study to fully disentangle.

Despite these limitations, the study offers meaningful contributions to the literature on student belonging, particularly for students with intersecting marginalized identities, and provides actionable insights for institutional strategies that support inclusive and affirming learning environments.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Committee

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Internal Review Board of Eastern Kentucky University (11/21/2024; No. 6121).

Consent to Participate and Publish

Informed consent was obtained from all participants for both participation and publication.

Funding

No funding was provided from any source for the research or publication.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to our student assistants who provided support reviewing the literature, Cheyenne Morton and Lauren Rose. We would also like to thank undergraduate research assistant Rebecca Barnes Slone for her assistance in analyzing the qualitative data.

References

Alotaibi, T. A., Alkhalifah, K. M., Alhumaidan, N. I., Almutiri, W. A., Alsaleh, S. K., AlRashdan, F. M., Almutairi, H. R., Sabi, A. Y., Almawash, A. N., Alfaifi, M. Y., & Al-Mourgi, M. (2023). The benefits of friendships in academic settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus, 15(12), e50946. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.50946

Allen, K., & Bowles, T. (2013). Belonging as a guiding principle in the education of adolescents. Australian Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology, 12, 108–119. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1002251.pdf

Allen, K.-A., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Waters, L. (2016). Fostering school belonging in secondary schools using a socio-ecological framework. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 33(1), 97–121. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2016.5

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Bickle, M.C., Rucker, R.D., & Burnsed, K.A. (2019). Online learning: Examination of attributes that promote student satisfaction. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 22(1), 1-8. https://ojdla.com/archive/spring221/bickle_rucker_burnsed221.pdf

Burgin, A., & Munasinghe, A. (November 21, 2024). The importance of institutional belonging | WGU Labs. https://www.wgulabs.org/posts/institutional-support-matters-when-it-comes-to-belonging-research-brief

Burke, K., Larmar, S. (2020). Acknowledging another face in the virtual crowd: Reimagining the online experience in higher education through an online pedagogy of care. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45 (5) 601-615.

Chen, S. (July 15, 2024). Belonging in online environments: Research brief. WGU Labs. https://www.wgulabs.org/posts/belonging-in-online-environments-research-brief

Farrell, O., & Brunton, J. (2020). A balancing act: a window into online student engagement experiences. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-020-00199-x

Garrison, D. R. (2017). E-learning in the 21st century: A community of inquiry framework for research and practice. (3rd ed). Routledge.

Garrison, D. R. (2007). Online community of inquiry review: Social, cognitive, and teaching presence issues. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(1), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v11i1.1737

Gopalan, M., & Brady, S.T. (2020). College students’ sense of belonging: A national perspective. Educational Researcher, 49(2), 134–137. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X19897622

Hansen-Brown, A., Sullivan, S., Jacobson, B., Holt, B., & Donovan, S. (2022). College students’ belonging and loneliness in the context of remote online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Online Learning, 26(4), Section II. https://olj.onlinelearningconsortium.org/index.php/olj/article/view/3123

Kaufmann, R., Vallade, J.I. (2022). Exploring connections in the online learning environment: Student perceptions of rapport, climate, and loneliness. Interactive Learning Environments, 30(10), 1794-1808.

Maghsoodi, Amir H., Nidia Ruedas-Gracia, & Ge Jiang. (2023). Measuring College Belongingness: Structure and Measurement of the Sense of Social Fit Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 70(4), 424–435. https://occrl.illinois.edu/docs/librariesprovider2/briefs---non-project/Measuring-College-Belongingness-Structure-and-Measurement-of-the-Sense-of-Social-Fit-Scale.pdf

Maslow, A.H. (1958) A dynamic theory of human motivation (p. 26-47). In Understanding Human Motivation. A. H. Maslow. Howard Allen Publisher.

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2023). Undergraduate enrollment: Condition of education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences.https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cha.

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2024). Condition of education. U.S. Department of Education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED652152.pdf024

Pedler, M.L., Willis, R. & Nieuwoudt, J.E. (2022). A sense of belonging at university: student retention, motivation and enjoyment. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 46(3), 397-408. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1955844

Ragusa, A.T., Crampton, A. (2018) Sense of connection, identity and academic success in distance education: Sociologically exploring online learning environments. Rural Society, 27(2), 125-142

Roddy, C.,D.L. Amiet, J. Chung, C. Holt, L. Shaw, S. McKenzie, F. Garivaldis, J.M. Lodge, M.EMundy (2017). Applying best practice online learning, teaching, and support to intensive online environments: An integrative review. Frontiers in Education, 2, 1-10.

Rose, E. (2017). Beyond social presence: Facelessness and the ethics of asynchronous online education. McGill Journal of Education, 52(1), 17-32.

Sandstrom, G. M., & Rawn, C. (2015). Embrace chattering students: They may be building community and interest in your class. Teaching of Psychology, 42(3), 227–233.

Strayhorn, T. L. (2019). College students' sense of belonging: A key to educational success (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315297293

Štremfel, U., Šterman Ivančič, K., & Peras, I. (2024). Addressing the sense of school belonging among all students? A systematic literature review. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(11), 2901–2917. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14110190

Thomas, L. (2012). Building student engagement and belonging in higher education at a time of change: Final report from What works? Student Retention and Success Program. Paul Hamlyn Foundation. https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets.creode.advancehe-document-manager/documents/hea/private/what_works_final_report_1568036657.pdf

Zhan, Z. & Mei, H. (2013). Academic self-concept and social presence in face-to-face and online learning: Perceptions and effects on students’ learning achievement and satisfaction across environments. Computers & Education, 69, 131-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.07.002

Zhao, S., & You, L. (2024). Exploring the Impact of Student-Faculty Partnership on Engagement, Performance, Belongingness, and Satisfaction in Higher Education. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 30(2), 180–197.