Abstract

This paper outlines the course, Essentials of Online Teaching, at Penn State's World Campus. The course leverages the Community of Inquiry (CoI) model to quickly develop effective online instructors by focusing on four key behaviors: communication, facilitation, feedback, and fostering a climate of belonging. The course aims to address the needs of instructors new to online teaching, helping them improve student community and retention. Institutions with well-designed courses that meet quality assurance criteria for course design but face the challenge of quickly developing effective online instructors may find this approach valuable for replication or adaptation.

Introduction

As the demand for online programs continues to rise, so does the demand for effective instructors who are able to meet the needs of a rapidly evolving student population. Conversations with academic partners and students have identified the need for emphasis on online pedagogy, instructor presence, and student engagement. To address these demands, World Campus Online Faculty Development has begun a systematic revision of our course portfolio starting with our introductory course, Essentials of Online Teaching. The underlying framework for this work is the practical application of the Community of Inquiry (CoI) model that focuses on four online teaching behaviors— communication, facilitation, feedback, and fostering a climate of belonging. Other institutions who have well designed courses that meet quality assurance criteria but face the challenge of developing effective online instructors quickly may be interested in replicating or adapting this approach.

The Community of Inquiry model by Garrison, Anderson, and Archer (2000) fulfills the stated needs of our academic programs and students. As our instructor participants come from a variety of backgrounds— academic, industry, technical experts, non-native speakers of English— many of whom have never learned, let alone taught online, it was imperative that we design an approach grounded in evidence but designed for instructors not interested in esoteric pedagogical theory. 25 years after its inception, CoI the remains a leading framework for online teaching and learning practitioners (Fiock 2020; Hulett and Gray 2023; Garrison 2022; Akbulut, et al. 2022).

Community and (Online) Learning

Dewey’s (1938) reflective thinking cycle (problem → exploration → integration → resolution) emphasized inquiry as a collaborative, reflective activity requiring dialogue and shared problem-solving. Any development of the individual, including educational development and specifically higher order development, is best achieved in a community. The CoI model applies this philosophy to the online learning environment establishing that “participants . . . construct meaning through sustained communication” (Garrison et al., 2000, p. 89). Swan et al. (2009) establish the connection between Dewey’s theory and its influence on the CoI model. They write:

The CoI framework is a dynamic model of the necessary core elements for both the development of community and the pursuit of inquiry, in any educational environment. Its three core elements— cognitive, social and teaching presence— … are viewed as multidimensional and interdependent ... At their core is the unity of a collaborative constructivist learning experience consistent with the legacy of John Dewey (5).

The three presences— cognitive, social, and teaching presence— within the CoI model are interdependent, often visualized as a Venn diagram (Garrison et al., 2000). Each are critical to community in the online learning environment. Social presence is “the ability of participants in a community of inquiry to project themselves socially and emotionally, as ``real'' people (i.e., their full personality), through the medium of communication being used” (Garrison et al., 2000, p. 94). Research has established that both instructor and student presences are a part of social presence in the course (Pollard & Swanson, 2014; Rovai, 2000). Cognitive presence is the ability of participants to construct meaning while interacting with course content and their community. Garison et al. (2000) qualify, “As essential as cognitive presence is in an educational transaction, individuals must feel comfortable in relating to each other” (94). Teaching presence is described as the “binding element” in CoI, the presence of an expert who guides and illuminates (Garrison et al., 2000). It encompasses course design, facilitation, and the direction of cognitive and social processes.

Factors Influencing Design

During the early 2010’s, World Campus Online Faculty Development courses were designed to mimic the asynchronous online experience of our World Campus students, albeit in an abridged version. Our audience, at that time, was mostly faculty members who were both authoring courses and preparing to deliver them. For that reason, our Essentials of Online Learning course contained a mixture of design and teaching topics. Designed courses were passed from one faculty member to another within academic departments, with many new instructors wanting to redesign parts of the course to fit their teaching philosophy.

In 2023, Online Faculty Development met with academic partners who required all instructors to complete The Essentials of Online Learning course prior to teaching. The goal was to obtain course design feedback. An overwhelming number of participants indicated that focus of the course should be solely on instruction and not on course design. They further expressed that course design content was not relevant to their part-time instructors who would never be asked to design or make changes to the courses they teach.

At the same time, World Campus experienced a dramatic increase in traditional-aged students in their programs. From the ‘19/’20 to the ‘24/’25 academic years the average age of dropped from 31 to 29 while the percentage of undergraduate students, which consistently trend younger, rose from 23.4% to 36.3% across the same academic years (World Campus Fast Facts Dashboard, 2025). (Note: these statistics are from an unpublished, World Campus internal report and do not represent official university data.)

An internal qualitative focus group study on student retention of World Campus faculty members and students conducted by World Campus strategic planning and an external consultant framed two foci pertinent to Online Faculty Development courses: What are the keys to students staying enrolled? And what are the keys to students’ academic performance? Traditional and adult learners in the survey stated different enrollment and academic challenges. In general, adult learners indicated non-academic challenges and the need for greater flexibility to accommodate for conflicting responsibilities. Traditional students indicated more academic challenges such as workload, instructor facilitation, timely feedback and connection to Penn State resources. These are all factors Online Faculty Development could address in a new course.

Operationalizing the Community or Inquiry Model

As a part of an institution of higher education, Online Faculty Development grounds course content in academic literature and evidence-based practice. However, as a development unit that is charged with rapidly upskilling instructors, we recognize that our mission is not to teach the literature and theories as an academic subject. Our mission is to quickly prepare instructors to be effective online instructors, not prepare them for academic discourse in pedagogy. One approach to preparing effective online instructors is to provide frameworks related to theory that allow instructors to rapidly understand the desired behaviors in an online classroom and to promote evidence based, best-practice examples.

To help our instructors efficiently prepare we developed a four-week course containing the following four modules:

- Being Present and Engaged,

- Fostering a Climate of Belonging,

- Preparing to Teach Online, and

- Developing a Reflective Practice.

The first three modules operationalize the CoI model and are discussed below.

Being Present and Engaged

This module grounds our participants in the CoI model with a brief overview of the model that underscores the importance of community and the three presences. During the introduction of CoI, participants are asked reflection questions about each presence to prompt them to consider instructor behaviors in the online classroom that foster a sense of community.

Table 1

Definitions of the presences within the CoI model and reflections questions as they appear in Essentials of Online Teaching

| Presence | Definition in the Course | Reflection Question |

| Social | The degree to which the learner feels connected to the instructor and their peers | How might an instructor create social presence in an asynchronous online classroom? |

| Teaching | Course design, facilitation, and the direction of cognitive and social processes. | What is the right level of instructor participation in asynchronous discussions? |

| Cognitive | The ability of learners to construct meaning through discourse and reflection within their community | Where does cognitive presence occur in the asynchronous online classroom? |

After the introduction to CoI, the course presents the three key behaviors needed to develop strong social, teaching, and cognitive presences— communication, facilitation, and feedback— chosen to operationalize the behaviors that contribute to community and effective online teaching.

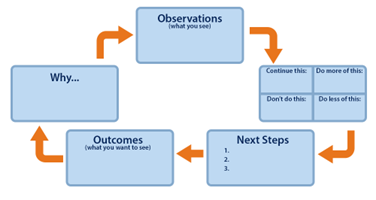

Figure 1

Instructor presence in an online course

In the course, communication is defined as the regular messages that you send about course logistics, assessment criteria, and outcomes. Facilitation is described as the act of using your expertise to keep your students engaged in the right ways with each other and content. And, feedback is observations provided to the student about performance on activities and assessments that are specific, actionable, timely, balanced and consistent.

In this framework communication encompasses both social presence and teaching presence. Participants are encouraged to reflect on the aspects of personal and professional identity that they want to project in the course. They are also asked to plan a communication cadence. Communication also impacts teaching presence as participants identify at what point guidance is needed about course logistics.

Facilitation is firmly grounded in teaching presence. Participants reflect on approaches for discussion board facilitation, are encouraged to set explicit expectations for interactions in the course, identify sections of the course in which students may have barriers to learning, gather guidance and supplemental materials, and reflect on modeling inclusive behaviors.

Feedback contains elements of both teaching and cognitive presence. Effective feedback should both guide students about where to find resources to improve (teaching presence) and direct the cognitive process to improve learning (cognitive presence). We present the framework for effective feedback developed by Zelinski et al (2019) as a model to achieve feedback that is specific, actionable, timely, balanced and consistent (Zelinski et al., 2019). Figure 2 shows this model adapted from the publication. Participants practice effective feedback by using the model to revise poor feedback.

Figure 2

The framework for effective feedback adapted from Zelinsky et al. (2019)

This framework encompasses many of the best-practice techniques that one would typically find in a course for online instructors. Fendler (2021) writes, “The most common techniques used by online teachers to achieve presence are frequently posting written announcements [communication], providing clear written instructions on assignments [facilitation], offering students meaningful written feedback [feedback], and timely responding to emails [communication]” (para.1). Instead of a laundry list of techniques, however, the framework focuses the participants’ attention primarily on behaviors, with examples of evidence-based techniques provided in the course and presented by participants in discussions.

Fostering a Climate of Belonging

Garrison (2017) writes that CoI is a “Collaborative experience which includes a sense of belonging and acceptance in a group with common interests” (p. 35). The second model focuses on techniques to help the instructor foster belonging in their course. Course participants reflect on their beliefs about teaching and students, examine course policies and interaction guidelines, and read about techniques for fostering a climate of belonging adapted from How Learning Works (Ambrose et al., 2010). As World Campus Students are highly diverse— representing not just diversity of culture and identity but also diversity of age, experience, and educational goals— participant instructors are encouraged to teach the whole student and are presented resources about the needs of specific populations attending World Campus courses. Ambrose et al. (2010) write,

[I]t is important to recognize the complex set of social, emotional, and intellectual challenges that college students face. Recognition of these challenges does not mean that we are responsible for guiding students through all aspects of their social and emotional lives... However, by considering the implications of student development for teaching and learning we can create more productive learning environments. (p. 134)

Preparing to Teach Online

Module 3 presents general tips for orienting yourself to a new course, information about time management, and institutional resources. The sections on institutional resources contain crucial knowledge for an instructor in a CoI because the instructor is the bridge between the course community and the larger institutional community. Knowing who to direct students to at the library, where students get general tech support, where to go for support with course technology when there is a problem, how to implement academic adjustments are examples of crucial skills that aid in course facilitation. In addition, instructors are considered more than just teachers and experts in the field. Students often view an instructor as a leader, mentor, and guide in their academic experience. Instructors may encounter students experiencing personal issues or extenuating circumstances such as the sickness of a loved one or a natural disaster in their section of the world. While instructors are not expected to be counselors, knowing what resources to direct students to in times of need is important to the CoI. A recommendation to the correct resource may make the difference between stopping out and finishing a semester.

Conclusion and Opportunities for Research

Essentials of Online Teaching is designed to meet the need to quickly and efficiently upskill online instructors at a large research institution with a mature instructional design unit. Comparative research should be done that explores the similarities and differences among our framework and others that use the CoI model.

Barriers still exist to reaching part-time instructors who may not be compensated for time spent on a month-long asynchronous professional development course. Further study into alternate approaches is warranted to ensure that these individuals receive both educational support and compensation for their time and effort.

Finally, there is limited direct research specifically examining instructor knowledge of institutional resources within the CoI framework. Although the connection is logical and supported by broader research, there is a need for more targeted studies that explicitly examine how instructor knowledge and proactive use of institutional resources impact the development and sustainability of a CoI in online courses.

References

Akbulut, M. S., Umutlu, D., Diler, O. N. E. R., & Arikan, S. (2022). Exploring university students’ learning experiences in the COVID-19 semester through the Community of Inquiry framework. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 23(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.1050334

Ambrose, S.A., Bridges, M.W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M.C., & Norman, M.K. (2010). How learning works: 7 research-based principles for smart teaching. Jossey-Bass.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education (7th printing, 1967). New York: Collier.

Essentials of Online Teaching. Unpublished course. (Retrieved April 25, 2025).

Fendler, R. J. (2024). Improving the “other side” to faculty presence in online education. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 27(1). https://ojdla.com/articles/improving-the-other-side-to-faculty-presence-in-online-education

Fiock, H. S. (2020). Designing a community of inquiry in online courses. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 21(1), 135–153. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v20i5.3985

Garrison, D. R. (2022, May 6). Faculty development and the Community of Inquiry. The Community of Inquiry. https://www.thecommunityofinquiry.org/editorial34

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2), 87–105.

Garrison, D. (2017). E-learning in the 21st century: A Community of Inquiry framework for research and practice (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Hulett, K. H., & Gray, M. (2023, June 21). Inquiring minds want to know…About social, cognitive, and teacher presence online. The Scholarly Teacher. https://www.scholarlyteacher.com/post/inquiring-minds-want-to-know-about-social-cognitive-and-teacher-presence-online

Pollard, H., Minor, M., & Swanson, A. (2014). Instructor social presence within the Community of Inquiry framework and its impact on classroom community and the learning environment. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 17(2). https://ojdla.com/archive/summer172/Pollard_Minor_Swanson172.pdf

Rovai, A. P. (2000). Building and sustaining community in asynchronous learning networks. Internet and Higher Education, 3, 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(01)00037-9

Swan, K., Garrison, D. R. & Richardson, J. C. (2009). A constructivist approach to online learning: the Community of Inquiry framework. In Payne, C. R. (Ed.) Information Technology and Constructivism in Higher Education: Progressive Learning Frameworks. Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 43-57.

World Campus Fast Facts Dashboard. Unpublished report. (Retrieved April 25, 2025).

Zelenski, A. B., Tischendorf, J. S., Kessler, M., Saunders, S., MacDonald, M. M., Vogelman, B., & Zakowski, L. (2019). Beyond "read more": An intervention to improve faculty written feedback to learners. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 11(4), 468–471. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-19-00058.1