Abstract

Undergraduate students often indicate they prefer a flexible course schedule and pace when completing asynchronous online courses, often in an effort to balance their academic commitments with their personal and professional obligations. While students must focus on their time management skills when taking an online course, faculty often have control of both the course schedule and pace in which the student is able to move through the course. In a study conducted at a large, comprehensive public university, the author collected data to measure the relationship between student performance in an online asynchronous undergraduate course based on three different course learning models, each using varying course schedules and course pacing methods: instructor-regulated staggered release, instructor-regulated all-at-once release, and student-regulated all-at-once release. The quantitative study indicated insignificant differences between the median grades of each learning model, but concluded the distribution of lower grades was higher in the student-regulated, all-at-once course delivery option. This study suggests that providing increased levels of flexibility using different course scheduling and pacing options may not be beneficial for all students in the asynchronous online learning environment, yet not a significant difference to warrant the minimization of flexible course offerings.

Introduction

Online learning has become a conventional delivery mode for teaching and learning in higher education (Wright et al., 2023). Regardless of the subject area, the Covid-19 pandemic accelerated the migration to online learning at many higher education institutions (Guler, 2023) (Wright et al., 2023). According to the 2022 data from the National Center for Education Statistics, nearly 54% of undergraduate students took at least one online course, with a quarter of students completing their degree exclusively using distance education courses. In comparison to pre-pandemic statistics, that is nearly a 20% increase in online course enrollment and a 10% increase in exclusive online education utilization (National Center for Education Statistics, n.d., Table 311.15). Online education is here to stay and expected to grow nearly nine percent each year over the next decade (Arnold, n.d.).

Many program administrators were forced to facilitate the move to online learning during the pandemic to not only meet the financial needs of the program and university, but also to ensure student progression to graduation. Despite the commotion to quickly do so, program administrators are realizing the benefits of online delivery for their program. While some programs had to return to on-campus teaching simply due to the nature of the content being taught, others have chosen to continue with exclusive online delivery modes for their courses. Not only are online courses more cost-effective to deliver, they also help with the shortage of resources and facilities that are required to conduct on-campus classes (Castro & Tumibay, 2021). The real estate needs for faculty on campus dwindle, in addition to the other ancillary costs that come with a face-to face work environment. The move to exclusive online teaching also can help with the faculty shortages many program administrators are experiencing. Remote faculty positions bring a much larger pool of potential applicants and increase the odds of hiring more qualified and experienced instructors for the program. Offering degree programs exclusively online has been an answer to many of the obstacle’s administrators have been experiencing in higher education.

In addition to the benefits for program administrators, online courses are eagerly accepted by undergraduate students (Wakeling et al., 2018). While more and more program directors and educators are now embracing online course delivery, research affirms the online learning environment is valued and often preferred by students (Soffer et al., 2019). Unlike with face-to-face courses where faculty help regulate learning in the classroom, online education often provides students with higher levels of autonomy and low levels of instructor presence (Jansen et al., 2020) (Jin, 2023). In many cases, remote learning is attractive to students because it can provide additional learning opportunities (You, 2016) than traditional, campus-based education (Jansen et al., 2020). Students learn in unsupervised situations where they make active decisions about their own study (Carvalho, 2016, as cited in Wakeling et al., n.d.) The flexibility that comes with online courses allows for more personalized learning because students are able to decide when, where, and what they can learn based on their individual preferences and schedule (Soffer et al., 2019). Students perceive this flexibility as beneficial because it allows them to better juggle their personal and professional commitments and therefore is a key factor why students ultimately choose to enroll in online courses (Soffer et al., 2019). A 2024 online survey of demands and preferences of online college students found that sixty percent of respondents reported they preferred enrolling in an asynchronous online course when given the various options for distance education courses (Aslanian & Fischer, 2024).

In addition to flexibility, students appreciate the elimination of transportation costs that are often associated with attending on-campus classes. This cost savings leads to an overall decrease in the cost of attendance, as moving and living expenses associated with on-campus courses are also eliminated. In some cases, online tuition rates are less expensive than out-of-state tuition rates, essentially opening the door for a student to affordably attend a school outside their immediate area without having to relocate.

Students, in particular online learners, have become strategic planners. They are researching programs, calculating costs and benefits, and demanding flexible options (Homan, 2024). There is more competition than ever in higher education so understanding this shift in mindset of students is crucial (Homan, 2024) for online program administrators in order to not only recruit, but also retain learners. With the recent reliance and immense growth of distance education, there is an increased awareness of the need to create accessible, equitable, and inclusive learning experiences for students (Wright et al., 2023). With that said, in addition to the competition online education has brought to the industry, the demand for research related to high-quality online learning has also increased (Wright et al., 2023) While flexible learning is often favored by students, there are other factors related to both course quality and student success that program administrators should consider prior to requesting faculty implementation in courses.

The scholarship of teaching and learning brings an abundance of studies comparing student performance in online courses to traditional face-to-face classes (Southard et al., 2016). Studies related to student perception, adoption of and integration of technology, and the overall concept of effective teaching strategies in the online learning environment are also easy to come by. Since the rapid expansion of online courses in the past few decades, scholars have identified several best practices for online teaching (Gillis & Krull, 2020). Best practices in an online course often center around ways faculty can best connect with their students in the virtual environment, the importance of providing clear learning objectives, the use of appropriate tools, and both prompt and regular communication with students (Gillis & Krull, 2020). In addition, instructional design should be used to control the content of the course, feedback given to learners, task structure, and the overall organization of the online learning environment (Costley & Lange, 2016).

Write et al (2023) found course design to be one of the main components to predict the quality of an online course. According to Jones and Blankenship (2017), investigating and analyzing how online courses are designed should be an integral part of online teaching methodology, in addition to learning the students’ preferences for their online experience. Returning to the 2024 online survey of demands and preferences of online college students, 30% of respondents indicated they would enroll at a more expensive institution if the learning format or schedule were ideal (Aslanian & Fischer, 2024). With that said, consideration of when courses are offered, length of courses, and overall flexibly of a course should be strongly considered by both administration and program directors in an effort to recruit and retain students in post-secondary institutions.

When students indicate they desire “flexible” online learning, there are a variety of ways in which the term can be interpreted by both students and faculty. Online learning in-and-of itself is considered to be more flexible than an in-person course on campus. Flexibility in online courses can refer to variances in a course schedule, pace in which the course is presented (or can be completed by students), types of assignments or assessments, and whether the course is delivered in a synchronous or asynchronous format. There are plenty of research studies evaluating each of these types of online course design, with some supporting increased flexibility and others discouraging it. Online learners are responsible for initiating, planning and conducting their studies, but many have expressed how difficult it is to maintain their motivation and persistence throughout a distance education course (Elvers et al, 2003, as cited in You, 2016). One could assume too much flexibility in an online course would exacerbate this for students. While good time management skills are essential for success in any online class, faculty tend to think they are supporting the students by choosing a schedule and pace they think best suits the subject area and population of learners enrolled in the course. While students often desire the highest level of flexible learning format, they do not always lead to effective learning (Soffer et al., 2019). Therefore, in order to understand the best way to integrate flexible course delivery options and support student learning, it is essential we continue to study how students make use of flexibility in online courses and evaluate how it relates to their performance in a course (Soffer et al., 2019).

The objective of this paper is to assess student performance using both varying course schedules (instructor-regulated verses self-regulated) and course pacing (staggered verses all-at-once) options in an effort to determine which course design method best facilitates student success in the online asynchronous learning environment. This paper does not evaluate student attitudes and perceptions of the varying course structures. While course pacing and course scheduling have been evaluated separately or for a short subset of a course, to the best of the author’s knowledge, no research has been conducted on how variances in both course scheduling and course pacing affect overall student performance in an asynchronous online course.

Background

While curriculum design is a critical step in course development, Robertson and Wakeling (2018) recommend faculty start designing an undergraduate course using the “Three S” course design method. The “Three S” design method suggests the instructor first determine the setting of the course (on-campus, online or hybrid), the learning style that will be used (passive or active), and the learning structure (instructor-regulated or student-regulated) that will be implemented (Robertson & Wakeling, 2018). This paper will solely focus on variance in learning structure, as the study was conducted exclusively in an online setting, and therefore used more of the default passive learning style (Robertson & Wakeling, 2018). Table: 1 provides an overview of the terms used to define varying learning structure options in this paper.

The passive learning style is similar to the traditional lecture-based on-campus course (Robertson & Wakeling, 2018). While active learning can be implemented in an online course using discussions, group-based activities, or simulations, using more of a passive learning style opens the door for additional flexibility in a course (Robertson & Wakeling, 2018). The selection of the best learning structure for an online course often centers around the university’s and program needs, faculty preferences, or decided based on the course content. When deciding on a course schedule, program directors, in conjunction with the teaching faculty, must determine if the course will be instructor-regulated or student-regulated.

The term “instructor-regulated” when referring to a course schedule is often used when faculty control the tempo at which students move through a course. Students are constrained by predetermined, communal deadlines that keep them progressing through the course using what the instructor thinks is a good pace. The entire class is bound together within the instructor’s timeline (Wakeling et al., 2018) and students have no control over how they progress through the course, nor do they have any flexibility for when assessments are due (Robertson & Wakeling, 2018). Other terms used for this type of course schedule is “instructor-paced”, “group based”, or a fixed-schedule course structure.

On the contrary, a “student-regulated” course scheduling model shifts accountability to the student (Robertson & Wakeling, 2018). This model requires students to create their own schedule and make their own study decisions (Robertson & Wakeling, 2018). Student-regulated online courses provide learners the most flexibility with learning. They are able to customize their learning to both their personal and educational preferences (Wakeline & Robertson, 2017) (Southard et al., 2016). They are able to work through the course when it best suits their schedule, often with instructors only having one due date for all assessments at the end of a course (Southard et al., 2016). Initially one may believe all online courses fall in the student-regulated category of course scheduling options as students generally teach themselves in distant learning courses. This is not to be confused with student-regulated learning (Robertson & Wakeling, 2018). When students must move through a course as a group, it is still considered to fall under the instructor-regulated course schedule model (Robertson & Wakeling, 2018).

When speaking of online course scheduling, it is difficult not to also address the concept of course pacing. There is certainly overlap between the two terms when reviewing the literature but for the purposes of this paper, course pacing will refer to the timing in which course content is made available for students to view (Bergamin et al., 2012). Essentially in this study, course pacing is referring to how transparent the content is to a student at the start of the class (Bergamin et al., 2012).

A conditional release of content refers to an instruction design pacing option where satisfactory completion of a module or assessment automatically unlocks the next segments of content for the student (University of Washington Tacoma, n.d.). This can be accomplished in an online course utilizing various settings in the learning management system. The conditional release course pacing option allows students to work at their own pace, while also requiring them to demonstrate they have a strong understanding of a particular content area before being permitted to move forward in the course. This pacing option is necessary in courses where mastery of content follows more of the Bloom’s Taxonomy process of learning. This pacing option was not used in this study due to the subject area of the course.

A scheduled or staggered release course pacing option is similar to a conditional release pacing option, but it is not focused on mastery of content and more geared toward faculty setting a pace for students in which they are expected to move through the course. With a staggered release, small chunks (usually organized in modules) of new content are released each week. The module becomes available to all students at a certain date or time regardless of the student’s progress in the course. The release of new content is not linked to any particular assessment or grade earned for an assessment. The staggered release design forces all students to move through the content in the course at the same time and allows students to focus on one module at a time (Bergamin et al., 2012).

An all-at-once course pacing option allows students to access the course in its entirety from the start (Bergamin et al., 2012). This open visibility pacing option provides the greatest transparency as students know exactly what is expected of them from the beginning. It allows students to work through the course content using their own schedule. While this option provides a new level of flexibility in a course, students may feel they can finish the course quicker by rushing through the content without having a thorough understanding of the concepts (Bergamin et al., 2012). In contrary, access to the entire course may cause a student to become overwhelmed (Bergamin et al., 2012).

Of course, every course schedule and pacing option does not lend itself to all subject areas and learning styles. As a program administrator, you will want to encourage faculty to meet the preferred flexible learning style needs of students, while creating a virtual environment and course design that aids in learning. From the perception of course design, both administrators and instructors wonder if course schedule and pace affect student success.

Table 1: Terms and definitions used for online course schedule and course pacing

| COURSE SCHEDULE | Term | Definition |

instructor-regulated, instructor-paced, group based, or fixed-schedule | The Instructor sets the schedule through which all students are to progress through the course. Learning is measured using scheduled, predetermined and sequenced assessments that occur at intervals throughout the course (Robertson & Wakeling, 2018). Students have minimal control over how they progress through the course nor when assessments will occur. | |

student-regulated, student-paced, self- paced or self-regulated | The student has full control of their progression through the course including timing of when the assessments will be completed. The student can progress through the course at their own speed with the only regulation being one deadline at the end of the course when assignments are due (Southard et al., 2016). This course schedule offers the most flexibility as students set their own goals and manage their own learning and performance in the course, based on their personal preference (Wakeling & Robertson, 2017) (You, 2016). | |

| COURSE PACING | staggered-release, scheduled release, linear sequencing, imposed pace model or manual release | Instructor sets definitive parameters regarding the timing and sequencing in which students can progress through a course (Wakeling & Robertson, 2017). Each unit or module in the course only becomes available to students at a certain date and time and students typically only focus on one unit at a time (Bergamin et al., 2012). All students move through the course together, engaging in the same learning activities at the same time (Bergamin et al., 2012) (Wakeling et al., 2018). While students typically are allowed to view previous modules, modules occurring in the future are not available until their assigned release day and time. |

all-at-once release or open visibility | All modules are available to all students for the entirety of the course and provides the greatest transparency of the course pacing options (Bergamin et al., 2012). The entire course is made available on day one and students can work on assignments out of order if they choose (Bergamin et al., 2012). |

The Study

Research Question:

The research question that guided this study includes:

RQ1: What is the impact on student performance in an online asynchronous course when using varying learning structures (self-paced or instructor-paced) and course pacing (staggered or all-at-once) options?

Experimental design

This research study surveyed students and analyzed their final course grades in three independent asynchronous online sections of the same course, each using a different combination of course scheduling and course pacing learning structures. (Table 2)

Instructor regulated, staggered content release:

Each semester, one section of the course was delivered using the instructor-regulated, staggered release learning model. With this course design method, students were given access to only one module per week. Due dates for assignments in each module occurred prior to the next module being available for students to view and complete. All students worked through the course content together at the same pace and were unable to work ahead. Learning occurred asynchronously and students had flexibility only with their daily schedule when working on the course (Wakeling & Robertson, 2017). This online learning model mimicked more of a face-to-face delivery method and would be considered the least flexible option for students in this study.

Instructor regulated, all-at-once content release:

The second section of the course in each semester would be considered a slightly more flexible option for students. Similar to the first section, the course was delivered using the same instructor-paced model, but with an all-at once release of the course content. At the start of the course, students were able to view all modules and assignments in the course, while still having the same required weekly due dates for assignments as the first section. Learning occurred asynchronously and students again only had flexibility as it pertained to their daily learning schedule (Wakeling & Robertson, 2017). Since students were able to view the entire course, they could work ahead if they chose, but the instructor-assigned due dates for assessments ensured the students were maintaining the pace designated by the faculty.

Student regulated, all-at-once content release:

The third and final section of the course in each semester presented the most flexible option by following more of a student-regulated, all-at once delivery model. Once again, students were able to view all modules and assignments in the course from the start, but were not provided with any weekly due dates for assignments to keep them on any particular pace. Instead, students were instructed to work through the course at their desired pace with all assignments needing to be submitted by a given date that fell at the end of designated term. This delivery method gave students complete autonomy and freedom within the confines of the course dates and allowed the students to self-manage their progress in the course.

The research using the three learning models above extended over one academic year, with each semester having 3 separate sections available for students to register. Each section was committed to and developed using one of the learning models prior to the opening of the course registration period. Students were able to register for the course during an open enrollment period with no advance knowledge of the predetermined course schedule and pace for each section.

Table 2: Differences in course schedule and course pacing in the 3 sections of the study

| Instructor-regulated, staggered content release | Instructor-regulated, all-at-once content release | Student-regulated, all-at-once content release | |

| Students were able to view the entire course and all assignments on day 1 | No | Yes | Yes |

| Students had required weekly due dates for assignments | Yes | Yes | No |

| Students were able to submit assignments for any module at any time during the course. | No | Yes | Yes |

Grade Performance Methodology

The university course used for this study was a 400, senior level Healthcare Management course. The course featured leadership content in support of personnel management, human resource concerns and effective team leadership that is often required in management positions within the healthcare arena. The course operated on a 7-week accelerated format, meaning an entire full semester of content was truncated into seven weeks. The Healthcare Management course is required of all Health Science majors and rated at three credits using the semester credit hour system. The course is consistently offered every semester and only in an asynchronous online format. Due to enrollment and faculty workload constraints, each section of the course had a maximum enrollment of 25 students.

It is important to note that each section of the course contained identical course design, course content (consisting of recorded lectures, content resources, assessments, and grading rubrics), class-wide communication, and experienced, tenured faculty of record (author). The course was delivered using the Canvas learning management system with course content organized in a modular format. Similar to chapters in a book, modules organize the subject material into logical units (Arnold, n.d.). The course was strategically designed to incorporate a variety of course activities and engagement between students, in addition to being logically structured and organized in regards to both the layout and navigation. With it being an accelerated course, the workload required students to study an average of 4 chapters per module, with each module requiring a submission of a written assignment, quiz or participation in an online discussion. In two of the seven modules, both a written assignment and discussion were required. In addition, students were required to create an audiovisual presentation on an assigned healthcare management topic. While the project was introduced to the class at the start of the course in the first module, the project submission was not due until the last day of the class. Delivery of the course, administration of quizzes, repository for all assignments, and classmate interaction all occurred entirely within the Canvas learning management system.

A student’s final grade in the course was determined using a culmination of assessments to ensure effective evaluation of student mastery of the course learning objectives. Student competency was evaluated using written assignments (3), discussions (2), quizzes (3), and completion of a course project. Each type of assignment carried a different weight toward the final grade calculation. Discussions contributed towards 20% of a student’s course grade, while written assignments 45%, quizzes 15% and the course project counting toward 20% of the course grade. No group-based assignments were required in the course in an effort to ensure each student could independently self-manage their participation and their course grade be based on their own efforts.

Canvas served as the repository for all assignments submitted in the course. Faculty evaluation of every submission was also communicated to the student in Canvas. With the exception of quizzes, all assignments were evaluated using a detailed grading rubric specific to the type of assignment. Each rubric contained 3 to 4 evaluation criteria with four rating levels for each criterion. Specific requirements for each rating level were provided in an effort to ensure consistent grading from one section to the other by removing as much subjectivity as possible from the evaluation process. Students in all sections were privy to the grading rubric prior to submitting every assignment. Grading for each assignment was completed within 3 business days of the date the student submitted the assignment, regardless of the section in which the student was registered. Quizzes typically contained 20 multiple-choice questions the computer randomly selected from a faculty approved test bank. The same random-selection test bank for each quiz was used in each section and students were given 60-minutes to complete each quiz.

A late policy was implemented for any work submitted in both of the instructor-paced delivery models. In order for a student to be allowed to submit an assignment after the due date, they were to request permission from the instructor prior to the due date for the assignment. Each day the assignment was submitted late, a 10% deduction from their earned score was implemented, per the course syllabus. Students who did not request additional time for an assignment prior to the due date, received a zero. In the student regulated, all-at-once content release delivery model, the late policy did not apply. Any assignments not submitted by the course end date received a zero.

Table 3: Alpha-Numerical Grade Conversion Chart

| Health Science Grading Scale | ||

| Letter Grade | Quality Points (GPA) | Numerical Grade |

| A | 4.000 | 96-100 |

| A- | 3.667 | 92-95 |

| B+ | 3.033 | 90-91 |

| B | 3.000 | 87-89 |

| B- | 2.667 | 85-86 |

| C+ | 2.333 | 82-84 |

| C | 2.000 | 78-81 |

| C- | 1.667 | 75-77 |

| D+ | 1.333 | 72-74 |

| D | 1.000 | 70-71 |

| F | 0.000 | 69-0 |

Data Collection

The sponsoring institution’s Institutional Review Board provided permission to conduct this study. The data collection for the study involved two separate processes: a short survey of students and collection of the final course grade for each student.

At the conclusion of the course, following final course grades being submitted to the university, students in each section of the course received e-mail correspondence from the instructor. The e-mail requested the student’s permission in allowing their course grade to be part of a study evaluating varying course schedules and course pacing options. Within the email was a link to the survey for students to complete, if they chose to participate. At the start of the survey, students were informed of the purpose of the study and that completion of the survey provided authorization for their final course grade and survey answers to be used in the research. The survey consisted of nine, closed-ended multiple choice questions requesting the student identify their demographics, online learning preferences, in addition to both their education experience and past performance in online course.

Participants

The study was conducted at a large, public, comprehensive university located in a major metropolitan area. Although the university is campus-based, it provides several online learning courses and majors.

The enrollment in the course for all sections offered in one academic year totaled 118 students, of which 81 students agreed to participate in the study. Tables: 4a and 4b below present the distribution of students based on course enrollment in each section, in addition to the demographics of the study participants by section.

The population of the students in the study mimicked the demographics of the students enrolled in the health science program with 85% of them identifying as female and nearly 70% between the ages of 18 and 35. It is important to note that given it was a senior level course, nearly 81% of the students had over 90 credit hours earned, with 69% reporting they had taken at least 6 online courses during their academic career. Students in the program are generally high achieving which was similar to those enrolled in each section of the course for this study. 91% of students enrolled in the course reported having a GPA of at least 3.0 or higher.

Table 4a: Distribution students in each course learning model of the study:

Number of students in the study n=81 | Instructor-regulated, staggered content release | Instructor-regulated, all-at-once content release | Student-regulated, all-at-once content release |

| 22 | 22 | 36 |

Table 4b: Demographic Information of study participants:

| Instructor-regulated, staggered content release | Instructor-regulated, all-at-once content release | Student-paced, all-at-once content release | ||||

| Variables | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | Frequency | % |

Gender | ||||||

| Male | 2 | 9 | 4 | 18 | 6 | 17 |

| Female | 20 | 91 | 18 | 82 | 30 | 83 |

Age | ||||||

| 18-24 | 11 | 50 | 11 | 50 | 7 | 19 |

| 25-35 | 9 | 41 | 8 | 37 | 19 | 53 |

| 36-45 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 9 | 9 | 25 |

| 46-55 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

Credit Hours Earned at the Start of the Course | ||||||

| 31-60 (sophomore) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 5 |

| 61-90 (junior) | 2 | 9 | 2 | 9 | 8 | 22 |

| 91+ (senior) | 20 | 91 | 19 | 86 | 26 | 72 |

GPA at the start of the course | ||||||

| 2.0-2.9 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 5 |

| 3.0-3.4 | 5 | 23 | 8 | 37 | 16 | 44 |

| 3.5-4.0 | 15 | 68 | 13 | 59 | 18 | 50 |

Number of Online Courses Taken prior to this course | ||||||

| 0-2 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 14 | 3 | 8 |

| 3-5 | 4 | 18 | 5 | 23 | 10 | 28 |

| 6-9 | 9 | 41 | 9 | 41 | 10 | 28 |

| 10+ | 9 | 41 | 5 | 23 | 13 | 36 |

Results

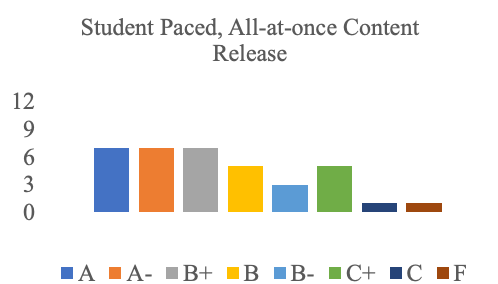

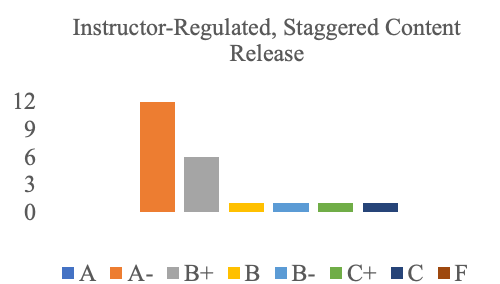

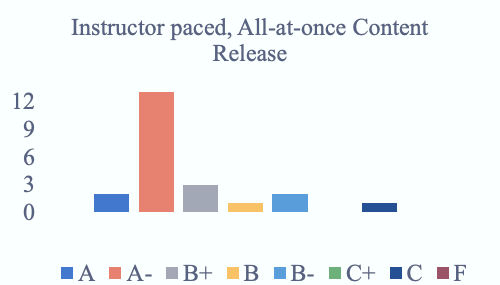

Due to the final course grade data being ordinal, a Kruskal-Wallis Test was conducted to compare the median grades between the three course types. The resulting p-value (p=0.2701) indicates there is no evidence the medians are significantly different from one learning model to another. Graph: 5a and Table: 5b provide a visual demonstration of the distribution of letter grades earned in each learning model.

Graph 5a: Letter grade distribution based on learning model

Table 5b: Letter grade distribution based on learning model

| Letter Grade | Instructor-regulated, staggered content release | Instructor-regulated, all-at-once content release | Student-regulated, all-at-once content released |

| A | 0 | 2 | 7 |

| A- | 12 | 13 | 7 |

| B+ | 6 | 3 | 7 |

| B | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| B- | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| C+ | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| C | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| F | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Based on both the table and graph above, we can conclude that although the median grades may not be significantly different between the course types, the exact letter grade distribution may vary slightly. The distribution of lower grades is higher for the “student-regulated, all-at-once content release” learning model. The median grade is slightly lower for that type of course as well.

Table 5c: Summary Statistics-Final Course Grade by learning model

| Instructor- regulated, staggered content release | Instructor-regulated, all-at-once content release | Student-regulated, all-at-once content release | |||||

| % | Letter | % | Letter | % | Letter | ||

| Median | 93.5 | A- | 93.5 | A- | 90.5 | B+ | |

| Mean | 90.9 | B+ | 92 | A- | 89.3 | B | |

| Min | 79.5 | C | 79.5 | C | 50 | F | |

| Max | 93.5 | A- | 98 | A | 98 | A | |

Limitations of the study

The small sample size of the study could bring concerns for its validity to the overall, general online learner population. The faculty researcher had limited data as nearly thirty-two percent of students who took the course did not complete the survey, and therefore did not consent to allowing their course grade be used in the study.

Successful flexible learning requires students to already possess some level of skill working independently and being able to self-govern their progress in a course to be able to effectively engage in learning activities (Bergamin et al., 2012). Students in this study were generally at a senior level towards degree progression, with nearly all students having experience learning in the online format from previous courses taken for the major. It is likely students in the course had developed self-discipline from their previous online education experiences and may have had the skills to appropriately tackle the course, regardless of the learning model. This factor could level the differences between the learning models in this study. In contrast, students with minimal online learning experience or students who were unaware of the consequences using a particular model may have different results. Studying without a schedule or being able to postpone studying could lead students to an inaccurate estimate of the time needed to complete the course. In the student-regulated, all-at-once learning model, procrastination could have led to decreased learning of the content and inferior submissions in order for the student to meet the deadline for the course. In addition, students in the study were not able to choose the course schedule and pacing method they preferred at the time of enrollment. If students were allowed to register for their preferred learning model, results may have varied, as well.

It is also important to reiterate that students in this study were from the same academic program. Naturally, senior level students in the same major often have developed friendships or created study groups with their classmates. It can’t be ignored there is a possibility a student in one of the all-at-once pacing models shared course information with a student in the faculty-regulated section. Ultimately, if that were the case, the student would have had more time to complete the assignment(s) than others in the same section of the course. The additional time to complete the assignment may result in a higher grade, ultimately skewing the results.

Student performance for this study was measured within the context of a single subject. Each module in the healthcare management course addressed a new leadership concept, each relatively unrelated to the other. If this study were conducted again, results could vary using a course with a different subject, varying levels of difficulty, or one where mastery of simpler concepts is required before comprehension of later topics can be accomplished.

Finally, none of the learning models prevented students from reaching out to the instructor with questions or requesting additional help with either understanding the course content or assessments. While the faculty had minimal individual interaction with students, the degree of instructor interaction directly with students could have altered course grades for those select students.

Discussion and Recommendations

In conclusion, program directors, instructional designers and faculty need to be aware that choosing and implementing a course schedule and pace that works for the overall program, instructor, and the students is the ultimate goal in any virtual classroom (Wright et al., 2023). Although the sample size is too small to generalize to the larger online education population, this evidence-based study contributes to the body of knowledge about the impact flexible learning models can have on student performance in an online asynchronous course. While the research in this study concluded there was no significant difference in the median grades between the learning models, it is still important to note the letter grade distribution does vary slightly between the models. As one would expect, the distribution of lower grades was higher for the student-regulated all-at-once delivery method in addition to the median grade for this model being slightly lower as well. Due to both the flexibility and self-regulated nature of that model, we can ultimately conclude the course design option providing the most flexibility may not always be providing an optimal learning experience for all students. However, based on literature regarding student preference in online courses mentioned earlier, it is likely students would choose more flexibility with the course schedule, than a slightly higher grade (Aslanian & Fischer, 2024).

This study was designed with replication in mind. Duplication of this study is encouraged to not only continue the analysis of varying pacing and scheduling options in online learning but also provide validation of the results. Further research should consider examining a larger sample of students and use courses from adverse disciplines or with a more varied population of students. It would also be noteworthy to duplicate the study using varying instructors for the same course to see if there would be variance in the results in that aspect. The use of other methodologies, including interviews with students and data mining from the learning management system, may shed more light on learning practices of the students and the affect instructor control has on student satisfaction and overall success in online asynchronous courses.

Depending on the program subject area, the findings of this study may have implications for program administrators, instructional designers, and faculty when they endure the development process for a new online course. Not only does the study provide insight regarding varying course schedules and pacing mechanisms used in online course design, it also supports increased flexibility in which students can complete a distance learning course. Post-secondary education administrators and program directors should take notice that flexible course schedules and pacing options can successfully be used as a way to increase student satisfaction, enrollment, and retention without jeopardizing student success.

Acknowledgements

Statistical analysis and interpretation were completed with the assistance of the Northern Kentucky University Burkardt Consulting Center (Highland Heights, KY).

References

Arnold, C. (n.d.). Online education market size, share, and growth: Global trends. LinkedIn.https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/online-education-market-size-share-growth-global-trends-chris-arnold/

Aslanian, C.B., Fischer, S., (2024) Online College Students Report 2024. 13th Annual Report on the Demands and Preferences of Online College Students. Education Dynamics. https://www.educationdynamics.com/the-online-college-students-report-2024/

Bergamin, B., Werlen, E., Siegenthaler, E., Ziska, S., (2012). The Relationship between Flexible and Self-Regulated Learning in Open and Distance Universities. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning. (13) 2 101-123.

Castro, M. D. B., Tumibay, G., (2021) A literature review: efficacy of online learning courses for higher education institution using meta-analysis. Education and Information Technologies. 26:1367-1385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-10027-z

Costley, J., Lange, C., (2016). The Effects of instructor Control of Online Learning Environments on Satisfaction and Perceived Learning. The Electronic Journal of e-Learning. 14 (3) 169-180.

Gillis, A., Krull, L., (2020). Covid-19 Remote Learning Transition in Spring 2020: Class Structures, Student Perceptions, and Inequality in College Courses. Teaching Sociology. 48(4) 283-299. DOI: 10.1177/0092055x20954263

Guler, K., (2023). Structuring knowledge-building in online design education. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, (33), 1055-1086. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-022-09756-z

Homan, J. (2024) . Understanding the Motivations and Needs of Online College Students. EducationDynamics. Retrieved from https://www.educationdynamics.com/the-online-college-students-report-2024/

Jansen, R. S., van Leeuwen, A., Janssen, J., Conijn, R., Kester, L. (2020) Supporting learners’ self-regulated learning in Massive Open Online Courses. Computers and Education. 146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103771

Jin, S., Im, K., Yoo, M., Roll, I., Seo, K. (2023). Supporting students’ self-regulated learning in online learning using artificial intelligence applications. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education. 20:37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00406-5

Jones, I., & Blankenship, D. (2017). Student perceptions of online courses. Research in Higher Education Journal, 32. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1148916.pdf

National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.). Table 311.15: Number and percentage of degree-granting postsecondary institutions that have an open admissions policy, by level and control of institution: Selected years, 2000-01 through 2018-19. Digest of Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_311.15.asp

National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.). Table 311.15: Number and percentage of degree-granting postsecondary institutions that have an open admissions policy, by level and control of institution: Selected years, 2000-01 through 2022-23. Digest of Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d23/tables/dt23_311.15.asp

Robertson, P., Wakeline, V., (2018). Three S’s of Undergraduate Course Architecture: Compatibilities of Setting, Style, and Structure. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration. https://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/spring211/robertson_wakeling211.html

Soffer, T., Kahan, T. & Nachmias, R. (2019). Patterns of Students’ Utilization of Flexibility in Online Academic Courses and Their Relation to Course Achievement. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 20(3). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v20i4.3949

Southard, S., Meddaugh, J., France-Harris, A., (2016), Can SPOC (Self-Paced Online Course) Live Long and Prosper? A Comparison Study of a New Species of Online Course Delivery. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration. http://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/summer182/southard_meddaugh_harris182.html

University of Washington Tacoma. (n.d.). Chunking, scaffolding, and pacing. Digital Learning. https://www.tacoma.uw.edu/digital-learning/chunking-scaffolding-pacing

Wakeling, V., Doral, M., Robertson, D., & Patrono, M. E. (2018). Perceptions of Undergraduate Students of Student-Regulated Online Courses. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration. https://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/fall213/wakeling_doral_robertson_patrono213.html

Wakeling, V., Robertson, P. R., (2017). A Comparison of Student Behavior and Performance between an Instructor-Regulated versus Student-Regulated Online Undergraduate Finance Course. Faculty Publications- Kennesaw State University. 4066.

http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/facpubs/4066

Wright, A. C., Carley, C., Alarakyia-Jivani, R., Nizamuddin, S. (2023). Features of high quality online courses in higher education: A scoping review. Online Learning, 27(1), 46-70. DOI: 10.24059/olj.v27i1.3411

You, J., (2016) Identifying significant indicators using LMS data to predict course achievement in online learning. Internet and Higher Education. 29, 23-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.11.003

Author Bio:

Shannon Fredrick, MHA, R.T. (R)(T) is an Associate Professor in the School of Allied Health at Northern Kentucky University where she teaches courses in Healthcare Management, Chronic Disease Management and Ethical and Legal Issues in Healthcare. She also serves as the program director for the Bachelor of Science in Health Science Program with over 12 years of experience in online higher education. Prior to transitioning to teaching, Shannon served in healthcare management roles and as a clinician in the fields of radiation therapy, radiography, and computed tomography.