Abstract

National University’s Master of Science in Educational Counseling underwent a revision in 2022 utilizing the approach of deriving program learning outcomes directly from the California Teaching Commission standards for school counselors. The program is offered solely in an online format. This study was undertaken to assess the program in terms of student self-assessment of teaching and learning both before and after the program revision to align with the professional standards. Data were collected from student end-of-course self-assessment questionnaires, revealing a statistically significant difference between the pre-realignment group (Group 1) and the post-realignment group (Group 2) in student perceptions of learning and teaching. These findings suggest that the revised, standards-aligned program may be more effective in enhancing student educational experiences. A Mann-Whitney U test was also conducted to evaluate whether students’ cohort and curriculum differed by students’ perception of teaching. The results indicated that students taking courses in the revised curriculum had significantly better perceptions of teaching than students who took courses using the previous curriculum, z = 5.70, p < .001. A Mann-Whitney U test was also conducted to evaluate whether students’ cohort and curriculum differed by students’ perception of learning. The results indicated that students taking courses in the revised curriculum had significantly greater perception of learning than students who took courses using the previous curriculum, z = 6.00, p < .001. Future research could explore the long-term impact of standards-aligned curricula on graduates' career readiness and professional success, further validating this approach to curriculum development. Additionally, investigating alternative assessment methods to capture more nuanced data on student learning outcomes and teaching effectiveness would enhance the validity of future studies.

Keywords: Education Counseling, Student Assessment of Teaching and Learning, Professional Standards

An Evaluation of a Professional Standards-Aligned Online Curriculum and Student Perceptions of Teaching and Learning

National University was founded in 1971 and dedicated to making life‐long learning opportunities accessible, challenging, and relevant to a diverse student population. Anchored by the core values of quality, access, relevance, accelerated pace, affordability, and community, National University is dedicated to educational access and academic excellence. The Sanford College of Education (SCOE) was established in 1980, and in 1996, online degree programs were established. The Educational Counseling programs at National University are housed in the SCOE. The program consists of two different pathways: community college counseling emphasis and the Pupil Personnel Service (PPS) School Counseling pathway, which is approved by the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing (2020).

Over the past three years, the Educational Counseling programs have transitioned and implemented new program learning outcomes aligned to the new state standards, established by the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC). As such, students enrolled in the older version of the programs are being taught out, and all remaining students in the legacy program were migrated to the new program through a curriculum crosswalk as of June 2024.

When enrolled in the Educational Counseling program at National, candidates receive an education that complies with the highest professional standards. The Counseling program complies with standards set forth by the Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP). The program has also been accredited by the California Commission on Teacher Credentials (CTC). Additionally, the program requires candidates to demonstrate mastery of a series of highly rigorous Program Learning Outcomes (PLOs). The PLOs were created directly from the professional standards and are as follows:

- PLO # 1 Implement the basic foundations of school counseling professional standards.

- PLO # 2 Advocate for all PK-14 students by employing anti-racist practice within educational foundations, growth, and development, learning theory, and academic achievement.

- PLO # 3 Perform as equitable-driven leaders and promote social justice efforts to enhance inclusivity and access for all.

- PLO # 4 Distinguish among major developmental theories of practice (personality, social, physical, emotional, and cognitive development) and chronological stages of human development that impact student academic development and life- long learning.

- PLO # 5 Examine, assess, and construct academic, social, and emotional comprehensive development programs with research-based practices.

- PLO # 6 Evaluate legal and ethical practices of professional school counseling.

- PLO # 7 Evaluate and assess program development for equitable outcomes.

- PLO #8 Demonstrate competence in the application of research methods.

National University’s Master of Science in Educational Counseling is committed to training candidates to provide best practices counseling services in educational settings. Toward this end, the curriculum was revised in 2022 to align with the professional counseling standards. The curriculum provides foundational knowledge and experience in the areas of human development and learning, contemporary and multicultural issues, comprehensive guidance programs, individual and group counseling, leadership and consultation, academic and career guidance, psycho‐educational, assessment, legal and ethical issues, and research. Clinical experiences, including practicum and field experience/internships with experienced supervisors, are a central component of the training candidates receive and allow the candidate to apply acquired knowledge and professional skills in field‐based settings. The professional counseling standards were the drivers of the curriculum revisions and the program learning outcome alignment.

Professional Counseling Standards

The California Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC) guidelines and standards influence the development of pupil personnel services (i.e., school counselor) training programs across California. In 2020, the CTC updated the School Counseling Preconditions, Program Standards, and Performance Expectations document to outline the essential components that all PPS training programs must adhere to. These standards shape the curriculum of school counselor training programs, and they offer a framework to ensure that candidates acquire the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to effectively support students. The School Counseling Preconditions, Program Standards, and Performance Expectations provide a roadmap for program development, implementation, and assessment to produce highly competent and culturally responsive school counselors. These program standards are outlined below.

- Program Standard 1: Program Design and Collaboration

Standard 1 stresses the significance of designing programs based on theory and research to prepare candidates for establishing student support systems. It requires collaboration with all stakeholders, such as parents, teachers, committees, educational institutions, and community organizations, to enhance program quality and efficacy.

- Program Standard 2: Preparation for School Counselor Performance Expectations

Focuses on equipping candidates with the abilities to meet the School Counselor Performance Expectations (SCPEs) through coursework and practical experiences. It provides opportunities for candidates to understand, apply, and engage in reflexive practice with each SCPE progressively throughout their program.

- Program Standard 3: Monitoring and Support

Standard 3 underscores the importance of overseeing candidate progress toward meeting credential requirements. It ensures that faculty members, program supervisors, and district-employed supervisors assist candidates in mastering SCPEs by offering evidence-based assessment tools for growth and development.

- Program Standard 4: Clinical Practice

Clinical practice provides candidates the opportunity to apply concepts in school settings through field experiences. During clinical practice, candidates receive continuous supervision in the school setting from both faculty members and district-employed supervisors.

- Program Standard 5: Determination of Candidate Competence

Standard 5 requires that school counseling programs utilize various methods to evaluate candidates’ knowledge, skills, and abilities in all training areas. Candidates must meet performance expectations and credential requirements before being recommended for the School Counseling Credential.

Performance Expectations (SCPEs)

The performance expectations define the abilities that school counselors need to lead counseling programs. These are outlined in the program learning outcomes. These outcomes encompass areas such as foundations of school counseling, professionalism, ethics, student development, leadership, advocacy, program development, research, and technology. The skills expected are evidenced directly in the language of the program learning outcomes, which are mapped throughout the curriculum and aligned to course learning outcomes. The standards and performance expectations serve as a guide for developing training programs that produce knowledgeable, skilled, and culturally responsive school counselors. By following these standards and performance expectations, school counselor training programs can ensure that candidates receive an education that equips them to address diverse student needs. They also prepare graduates to uphold these standards, advocate for equity and social justice, and lead school counseling programs (California Teacher Credentialing, 2020).

Literature Review

The development of curriculum in higher education, particularly in professional programs, is increasingly guided by professional standards. This approach ensures that students are well-prepared for their future careers and that the curriculum remains relevant and up-to-date. In the field of Educational Counseling, professional standards play a crucial role in shaping curriculum content and delivery. This paper explores how using professional standards to guide curriculum development, particularly in online settings, can lead to increased student satisfaction with their experiences of teaching and learning.

Online Student Satisfaction in Higher Education Courses

Online education rapidly expanded with the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2019, 36% of undergraduate students were enrolled in at least one online course. At the peak of the pandemic in 2020, 75% of undergraduate students were enrolled in at least one online course. This number declined to 61% in 2022 as the pandemic receded and face-to-face classes resumed at most universities. Undergraduate students enrolled exclusively in online courses expanded from 15% in 2019 to 44% in 2020 and settled at 28% in 2022 (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2023). Understanding student satisfaction in online learning has become increasingly important to university administrators and faculty as it has been empirically linked to student retention and success, and is a driving force in faculty performance and institutional ranking (Bornschlegl & Cashman, 2018; Hassani & Wilkins, 2022; Martin & Bolliger, 2022). As online enrollments have grown, institutions of higher education have increasingly focused on students’ satisfaction with their online courses and overall educational experience, and student, faculty, and institutional factors influencing online student satisfaction in higher education.

Factors Influencing Online Student Satisfaction

Researchers have linked online student satisfaction in higher education to a wide range of factors associated with students, instructors, and institutions. Factors found to positively influence student satisfaction with online courses and programs include social presence, teacher presence, cognitive presence, academic achievement, student engagement (including cognitive, emotional, and behavioral engagement), instructional design and course content, technology and infrastructure, and instructor-student interaction (Flener-Lovitt, 2020; Hazzam & Wilkins, 2023; Hensley et al., 2021; Holbeck & Hartman, 2018; Natarajan & Joseph, 2022; Shi et al., 2023). In this section, we limit our discussion to predominate factors that influence student satisfaction in online learning, presences (social, teaching, & cognitive presence), and student engagement (cognitive, emotional, & behavioral engagement) because these two factors often involve many of the other factors associated with student satisfaction, such as instructor-student interactions, course design and content, technology management, and academic achievement. Finally, we explore student satisfaction regarding individual courses vs. complete online programs, an area with limited research but of significant importance to understanding student satisfaction, retention, and academic achievement.

Social, Cognitive, and Teaching Presence. Garrison et al.’s (2000; 2010) Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework has seen widespread use in the research and practice of online and blended learning environments. The foundational assumption of CoI is that higher-level learning occurs best in the presence of learners who are engaged in critical reflection and discourse. The CoI framework posits three types of presence that are necessary for effective online learning: social presence, cognitive presence, and teaching presence (Garrison et al., 2010).

Scholars contend that social presence is a critical element of the optimal online learning environment and is positively associated with and predictive of student satisfaction (Holbeck & Hartman, 2018; Nasir, 2020; Natarajan & Joseph, 2022; Yang et al., 2013). Garrison (2009) defined social presence as “the ability of participants to identify with the community (e.g., course of study), communicate purposefully in a trusting environment, and develop inter-personal relationships by way of projecting their individual personalities” (p. 352). Social presence is the ability of online learners to connect with others authentically in the online environment and engage in meaningful collaborative learning as real people (Garrison et al., 2000) and shows up in the online courseroom as emotional expression, risk-free expression, open communication, collaboration, and group cohesion (Garrison et al., 1999).

Teaching presence is defined as “the design, facilitation and direction of cognitive and social processes for the purpose of realizing personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile learning outcomes” (Anderson et al., 2001, p. 5). Teaching presence occurs when instructors define and initiate discussion topics, provide direct instruction, demonstrate effective instructional management, and build understanding among students. Teaching presence overlaps with the other two presences and significantly positively influences social presence and cognitive presence (Garrison et al., 2010).

Cognitive presence reflects students’ ability to engage with the course material and to construct meaning from the learning experience through open communication. Other indicators of cognitive presence include exploring, connecting, and applying ideas, and a free exchange of information (Garrison et al., 1999, 2010).

Social presence is heavily influenced by both teaching presence and cognitive presence. In their study of two online programs (social science and education) involving multiple online courses, Garrison et al. (2010) found that teaching and social presence had a significant influence on perceived cognitive presence and that teaching presence was perceived to influence social presence. Social presence is needed for teaching presence to have a positive influence on learners and is the essential element for binding together social, teaching, and cognitive presence (Garrison et al., 2000; Shi et al., 2023). Educators who recognize and address the importance of all three presences in the design and delivery of online courses, improve the probability of enhancing student satisfaction in online courses.

Student Engagement. Student engagement and students’ perceptions of faculty engagement have been reported as critical elements for successful online teaching and learning (Alqurashi, 2019; Moore, 2005; Wright et al., 2023), and directly influence student satisfaction in higher education (Baloran et al., 2021; Lux et al., 2023; Roque-Hernández, 2023). Student engagement is also an indicator of student success (Henre et al., 2015). In the online environment student engagement refers to the level of active participation, interaction, and involvement that students exhibit in their courses with the course material, peers, and instructor (Hazzam & Wilkins, 2023; Henrie et al., 2015). Researchers have identified three dimensions of engagement in the online learning setting: cognitive engagement, emotional or affective engagement, and behavioral engagement (Fredricks et al., 2004, 2016; O’Conner, 2024; Sun & Rueda, 2012). Students demonstrate cognitive involvement when they invest in exploring course material, seek out additional readings and resources to better understand a topic or concept, and engage in discussion of academic topics in the online course room. Emotional engagement reflects student feelings about their online course or program, such as being excited about the course, its format, content, and supporting materials. Behavioral engagement has to do with students’ observable behaviors in relation to an online class such as task completion, turning in assignments on time, participation in online discussions, and interactions with peers and instructors (Sun & Rueda, 2012). The effective use of technology that provides easy access to the course and supporting materials, navigation across platforms, and integrating technologies that encourage and enrich interactions between peers and instructors can improve cognitive, emotional, and behavioral engagement in the online class (Hazzam & Wilkins, 2023; Hobeck & Hartman, 2018). Faculty who effectively use technology in the online class and who use charismatic leadership in their online classes encourage participation in learning activities, collaborative learning, and interactions in the course room (Hazzam & Wilkins, 2023; Queen, 2022). The interactive online learning environment inspires relationship-building between peers and instructors and promotes student engagement and student satisfaction in online courses. In conclusion, online student engagement is empirically linked to student satisfaction. Employing strategies that promote active participation, interaction, and connectedness in the online learning environment safeguards students course retention, academic achievement, and positive learning experience (Baloran et al., 2021; Bolliger & Martin, 2018; Lux et al., 2023; Roque-Hernández, 2023).

Online Courseload and Student Satisfaction

With the growth of online classes and virtual universities, the focus on student satisfaction and engagement in online learning is shifting from satisfaction with individual online courses to satisfaction with the educational experience that features most courses or an entire courseload online. Wright et al. (2023) noted that students’ overall educational experience is influenced not so much by taking an individual course here and there but by taking many courses online which can have greater effects on students’ relationships with peers and faculty, and improve academic performance, all of which can and do influence students’ overall satisfaction. Using the National Survey of Student Engagement data, several studies have reported conflicting outcomes on the impact of online courseloads on student interactions and student satisfaction. An early study by Chen et al. (2008) found that students who took all of their classes online had more interactions with faculty and fewer interactions with peers when compared to students in face-to-face classes. Dumford and Miller (2018) found that students taking a greater proportion of their courses online had lower student satisfaction. In the spring of 2021, during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, Wright et al. (2023) studied the effects of mostly or fully online classes vs. blended classes on students’ satisfaction with faculty engagement and academic satisfaction. The study used a sample of 2,123 undergraduates drawn from three 4-year universities in Boston. Wright et al. found that students who were in classes that met at least once a week face-to-face reported significantly higher satisfaction with faculty engagement and academic satisfaction when compared to students who never or rarely met in person. They noted that the effect was significantly less for Black and Asian students.

The research on the effect of mostly or completely online courseload on student satisfaction and engagement is limited. Further exploration is needed. More specifically, more understanding of the disproportionate effects of predominately online courseloads on students by race, ethnicity, and gender, and by student self-selection into online learning vs. students whose first option would have been face-to-face classes may reveal reliable predictors of student academic success, engagement, and satisfaction on the virtual campus (Morgan & Whip, 2007; Wright et al., 2023).

Applied Experiential Learning

Applied experiential learning has emerged as a critical pedagogical approach in online education, aimed at enhancing student engagement and skill development beyond traditional classroom settings. According to Radović et al. (2023), experiential learning emphasizes the active involvement of students in real-world scenarios where they can apply theoretical knowledge. This approach is particularly relevant in online classes, where creating meaningful learning experiences can be challenging (Chui, 2023) and especially challenging for online group work (Donelan & Kear, 2024). By integrating hands-on activities, simulations, and virtual labs, educators can bridge the gap between theory and practice, providing students with opportunities to develop practical skills (Kolil & Achuthan, 2024).

Applied experiential learning is an important learning approach to integrate into online curricula. Fitrianto and Saif (2024) underscored the effectiveness of applied experiential learning in online settings, highlighting its positive impact on student learning outcomes and learning retention. Chiu et al. (2023) argued that experiential learning fosters deeper engagement and critical thinking among students as they actively participate in problem-solving activities relevant to their field of study. Moreover, virtual environments and simulations can simulate real-world challenges, preparing students for future professional roles (Lin et al., 2023). This sentiment is echoed by Ahuja (2024), who emphasized that experiential learning activities in online education not only enhance academic achievement but also cultivate essential competencies such as teamwork, communication, and decision-making.

Furthermore, the integration of technology plays a pivotal role in facilitating applied experiential learning in online classes. Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) platforms offer immersive experiences that replicate authentic settings, allowing students to practice skills in a safe and controlled environment (Vairamani, 2024). These technological advancements enable educators to create interactive simulations and scenarios that enhance the learning experience and prepare students for diverse professional contexts (Ravichandran & Mahapatra, 2023; Tiwari et al., 2023).

Online Student Perceptions of Instructor Performance

Understanding online student perceptions of instructor performance is crucial for enhancing student satisfaction in virtual learning environments. Research indicates that students place significant value on instructor engagement and responsiveness in online courses (Gunness et al., 2023). Effective communication, timely feedback, and clear expectations are key factors that influence how students perceive instructor performance in digital classrooms (Lin et al., 2024). According to Schueler and West (2023), students appreciate instructors who demonstrate enthusiasm for the subject matter and demonstrate genuine interest in their learning progress, even in online settings. Moreover, the design and organization of online courses also impact student perceptions of instructor performance. Bervell et al. (2023) found that students value well-structured courses with organized content and easily navigable interfaces, which contribute to positive perceptions of instructor competence. Furthermore, interactive and multimedia-rich instructional materials can enhance engagement and improve student satisfaction with instructor performance.

However, challenges such as technical difficulties and inconsistent communication can negatively influence student perceptions of instructor effectiveness in online courses (Han & Geng, 2023). Students may perceive instructors as less effective if they encounter frequent disruptions in course delivery or experience delays in receiving feedback (Nussli et al., 2024). Therefore, it is essential for instructors to proactively address these issues and maintain a supportive online presence to foster positive perceptions among students. Online student perceptions of instructor performance are shaped by various factors, including communication effectiveness, course organization, and responsiveness. By focusing on clear communication, timely feedback, and course design, instructors can enhance their perceived effectiveness in online teaching and promote positive student experiences.

Study Methodology and Analyses

At the end of each National University course, students are asked to complete an online anonymous assessment questionnaire in which they assess items such as the extent of their learning in the course, their ability to use concepts learned in the course, instructor effectiveness, and value of course content items. Each of the items on the student end-of-course assessment questionnaire utilizes a five-point Likert scale response where the response value of “1” equals “not at all” and the value of “5” equals “very much.” The list of questions contained in the student-end-of-course questionnaire has two separate and distinct sections: (a) student perception of learning and (b) student perception of teaching.

For this study, the student-end-of-course questionnaire data for all educational counseling courses taught from July 2020 through June 2021 (Group 1: pre-revision students) and July 2022-June 2024 (Group 2: post-revision students) were analyzed using IBM SPSS. This consisted of data from 174 courses; N = 939, after listwise deletion of missing data N = 885 (i.e., students that answered all of the questions). Analyses for individual question means and bivariate correlations included all of the students who answered that question. First, a Spearman correlation analysis was conducted to assess the overall relationship between student perception of learning variables and student perception of teaching variables. Next, Spearman correlation analyses were conducted within both groups to assess the relationship between Group 1 student perception of learning variables and student perception of teaching variables and Group 2 student perception of learning variables and student perception of teaching variables. Third, a Mann Whitney U test was conducted to analyze whether there was a significant difference between the two groups on student perception of learning and teaching.

Findings

First, a Spearman rank-order correlation analysis was conducted to assess the overall relationship between student perception of learning and student perception of teaching. Specifically, the dependent variables were measured on a Likert scale and thus the data were ordinal. A Spearman correlation analysis found that every correlation between student perception of learning and student perception of teaching were highly correlated (overall mean = 4.43, SD = .22, N = 885). For example, there was a significant correlation between student perception of their ability to write improving and “I received useful comments on my work” (r = .72, p < .001) and “The instructor was an effective teacher” (r = .75, p < .001).

Next, Spearman rank-order correlation analyses were conducted within both groups to assess the relationship between Group 1 student perception of learning and student perception of teaching and Group 2 student perception of learning and student perception of teaching. Student perception of learning was highly correlated with student perception of teaching. For instance, in Group 1 (see Table 1), student’s perception of their ability to write improving was highly correlated with “The instructor was an active participant in this class” (r = .72, p < .001), “Instructor encourage students to think independently” (r = .79, p < .001), “Instructor was available for assistance” (r = .71, p < .001), “I received useful comments on my work” (r = .70, p < .001) and “The instructor was an effective teacher” (r = .78, p < .001). Students feeling like they gained significant knowledge was also highly correlated with “The instructor was an active participant in this class” (r = .67, p < .001), “Instructor encourage students to think independently” (r = .72, p < .001), “Instructor was available for assistance” (r = .70, p < .001), “I received useful comments on my work” (r = .67, p < .001) and “The instructor was an effective teacher” (r = .70, p < .001). Students critical thinking ability was also highly correlated with “The instructor was an active participant in this class” (r = .74, p < .001), “Instructor encourage students to think independently” (r = .77, p < .001), “Instructor was available for assistance” (r = .73, p < .001), “I received useful comments on my work” (r = .68, p < .001) and “The instructor was an effective teacher” (r = .77, p < .001).

Table 1

Group 1 Spearman Correlation Analyses

| Student Perception of Learning | Instructor was an Active Participant in Class | Instructor Encouraged students to Think Independently | Instructor was Available for Assistance | Received Useful Comments on Work | Instructor was an Effective Teacher |

Ability to Write | .72** | .79** | .71** | .70** | .78** |

Gained Significant Knowledge | .67** | .72** | .70** | .67** | .70** |

| Critical Thinking | .74** | .77** | .73** | .68** | .77** |

Note. **p < .001

For Group 2, student perception of learning was also highly correlated with student perception of teaching (see Table 2). For instance, student’s perception of their ability to write improving was highly correlated with “The instructor was an active participant in this class” (r = .71, p < .001), “Instructor encourage students to think independently” (r = .71, p < .001), “Instructor was available for assistance” (r = .68, p < .001), “I received useful comments on my work” (r = .71, p < .001) and “The instructor was an effective teacher” (r = .71, p < .001). Students feeling like they gained significant knowledge was also highly correlated with “The instructor was an active participant in this class” (r = .74, p < .001), “Instructor encourage students to think independently” (r = .72, p < .001), “Instructor was available for assistance” (r = .71, p < .001), “I received useful comments on my work” (r = .69, p < .001) and “The instructor was an effective teacher” (r = .74, p < .001). Students perception of learning variable of improved ability to think critically was also highly correlated with “The instructor was an active participant in this class” (r = .73, p < .001), “Instructor encourage students to think independently” (r = .74, p < .001), “Instructor was available for assistance” (r = .71, p < .001), “I received useful comments on my work” (r = .71, p < .001) and “The instructor was an effective teacher” (r = .72, p < .001).

Table 2

Group 2 Spearman Correlation Analyses

| Student Perception of Learning | Instructor was an Active Participant in Class | Instructor Encouraged students to Think Independently | Instructor was Available for Assistance | Received Useful Comments on Work | Instructor was an Effective Teacher |

Ability to Write | .71** | .71** | .68** | .71** | .71** |

Gained Significant Knowledge | .74** | .72** | .71** | .69** | .74** |

| Critical Thinking | .73** | .74** | .71** | .71** | .72** |

Note. **p < .001

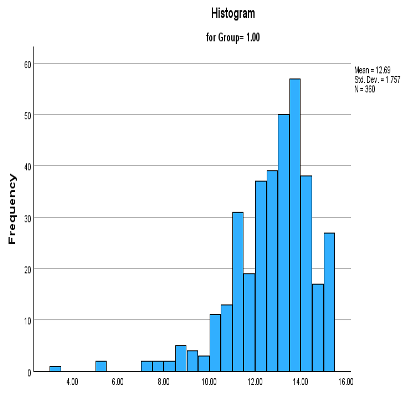

Lastly, because the dependent variables were measured on a 5-point Likert Scale, the assumptions of an independent-samples t-test were violated, therefore a Mann-Whitney U test was conducted to analyze whether there was a significant difference between the two groups on student perception of learning and student perception of teaching. All assumptions of a Mann-Whitney U test were met: 1) both dependent variables were measured at the ordinal level, 2) the independent variable consists of two categorical, independent groups (Group 1 and Group 2), 3) there is independence of observations between both groups in that no students in the first cohort were in the second cohort, and 4) the two independent groups have similar distribution shapes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Results of Normality Test

|  |

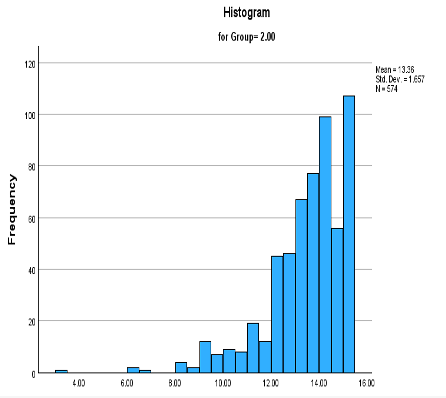

A Mann-Whitney U test was conducted to evaluate whether curriculum type (Group 1 and Group 2) differed by student perception of learning (Total N = 940). The results indicated that Group 2 (students taking courses with the revised curriculum) had significantly greater perception of learning than Group 1 (students that took courses using the previous curriculum), z = 6.00, p < .001 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Student Perception of Learning

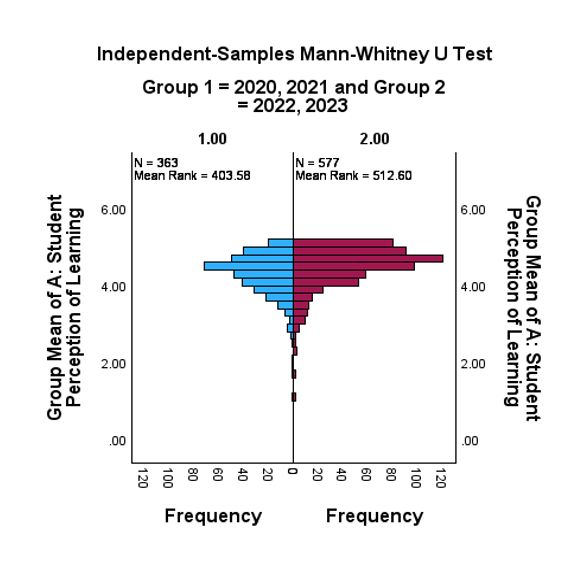

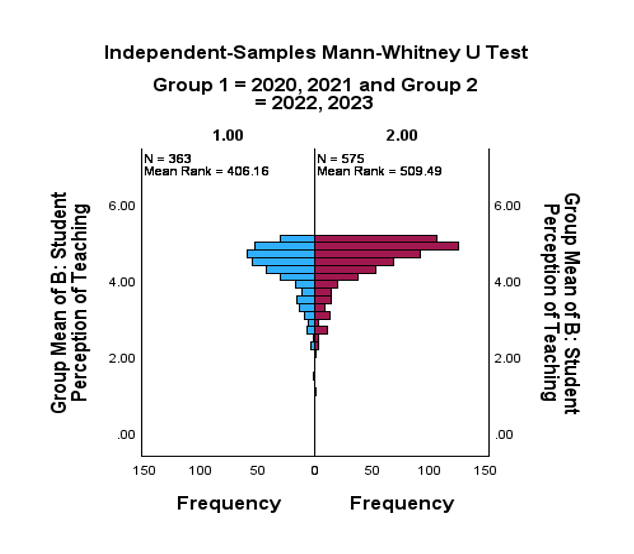

A Mann-Whitney U test was also conducted to evaluate whether curriculum type (Group 1 and Group 2) differed by student perception of teaching (Total N = 938). The results indicated that Group 2 (students taking courses in the revised curriculum) had significantly better perceptions of teaching than Group 1 (students that took courses using the previous curriculum), z = 5.70, p < .001 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Student Perception of Teaching

Conclusion

The use of professional standards to guide curriculum development, particularly in online educational settings, has significant benefits for student success. By ensuring relevance, comprehensiveness, currency, clarity, and quality in the curriculum, standards-aligned courses meet the needs and expectations of students across various course types. This study captured the overall positive outcomes of realigning the curriculum around professional standards.

The data used were from student end-of-course self-assessment questionnaires. Results show a statistically significant difference between Group 1 and Group 2 on student perception of learning and student perception of teaching. Although these results suggest that the revised program may be more effective in regards to student perception of learning and teaching, there are limitations: (a) students are not mandated to complete these questionnaires, therefore important information may have been lost in terms of those students who chose not to respond; (b) we relied on student self-assessments; (c) there was a lack of variability in the data, with most students responding with 4’s or 5’s; and (d) analyses were based off mean scores versus raw data, which was unavailable to the researchers. National University is working toward the development of better measures of student learning and instructor teaching, but clearance from the governance bodies needs to be resolved before any single standardized measure can be developed and implemented. For lack of a current better measure, the student end-of-course self-assessment questionnaire remains the best overall source of data at present but the use of the data and interpretation of the results must be tempered by an awareness of the data’s limitations.

The Master of Science in Educational Counseling program at National University exemplifies a standards-based approach, integrating professional standards throughout its curriculum to prepare students for successful careers in educational counseling. As the field of education continues to evolve, the importance of aligning curriculum with professional standards will likely grow. Future research could explore the long-term impact of standards-aligned curricula on career readiness and professional success, further validating the benefits of this approach to curriculum development.

References

Ahuja, V. (2024). Simulations in business education: Unlocking experiential learning. In V. Membrive (Ed.) Practices and Implementation of Gamification in Higher Education (pp. 1-21). https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-0716-8.ch001

Anderson, T., Rourke, L., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, R. (2001). Assessing teaching presence in a computer conferencing context. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 5(2), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v5i2.1875

Baloran, E. T., Hernan. J. T., & Taoy, J. S. (2021). Course satisfaction and student engagement in online learning amid COVID-19 pandemic: A structural equation model. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 22(4), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.1002721

Bervell, B., Owuyaw, K. E., Armah, J. K., Mireku, D. O., Asante, A., & Somuah, B. A. (2023). Modeling distance education students’ satisfaction and continuous use intention of students’ portal: An importance-performance map analysis. Information Development, 15, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2024.100431

Bornschlegl, M., & Cashman, D. (2018). Considering the role of the distance student experience in student satisfaction and retention. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 34(2), 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680513.2018.1509695

Chiu, M. C., Hwang, G. J., & Hsia, L. H. (2023). Promoting students' artwork appreciation: An experiential learning‐based virtual reality approach. British Journal of Educational Technology, 54(2), 603-621. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13265

Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2020). Pupil personnel services: School counseling preconditions, program standards, and performance expectations. https://www.ctc.ca.gov/educator-prep/stds-prep-program

Donelan, H., & Kear, K. (2024). Online group projects in higher education: Persistent challenges and implications for practice. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 36(2), 435-468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-023-09360-7

Fitrianto, I., & Saif, A. (2024). The role of virtual reality in enhancing experiential learning: A comparative study of traditional and immersive learning environments. International Journal of Post Axial: Futuristic Teaching and Learning, 2(2), 97-110. https://doi.org/10.59944/postaxial.v2i2.300

Flener-Lovitt, C. (2020). Using structure teams to develop social presence in asynchronous chemistry courses. Journal of Chemical Education, 97(9), 2519-2525. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00765

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concepts, state of evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59-109. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3516061

Fredricks, J. A., Filsecker, M., & Lawson, M. A. (2016). Student engagement, context, and adjustment: Addressing definitional, measurement, and methodological issues. Learning and Instruction, 43, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.02.002

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (1999). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher education, 2(2-3), 87-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Garrison, D. R. (2009). Communities of inquiry in online learning. In P.L. Rogers (Ed.), Encyclopedia of distance learning (2nd ed.), pp. 352-355. IGI Global.

Garrison, D.R., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Fung, T. S. (2010). Exploring causal relationships among teaching, cognitive, and social presence: Student perceptions of the community of inquiry framework. Internet and Higher Education, 13(1-2), 31-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.10.002Get rights and content

Gunness, A., Matanda, M. J., & Rajaguru, R. (2023). Effect of student responsiveness to instructional innovation on student engagement in semi-synchronous online learning environments: The mediating role of personal technological innovativeness and perceived usefulness. Computers & Education, 205, 104884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104884

Han, J., & Geng, X. (2023). University students’ approaches to online learning technologies: The roles of perceived support, affect/emotion, and self-efficacy in technology-enhanced learning. Computers & Education, 194, 104695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104695

Hazzam, J., & Wilkins, S. (2023). The influences of lecturer charismatic leadership and technology use on student online engagement, learning performance, and satisfaction. Computers & Education, 200, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104809

Henrie, C. R., Halverson, L. R., & Graham, C. R. (2015). Measuring student engagement in technology-mediated learning a review. Computers & Education, 90(1), 36-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.09.005

Hensley, A., Hampton, D., Wilson, J. L., Culp-Roche, A., & Wiggins, A. T. (2021). A multicenter study of student engagement and satisfaction in online programs. Journal of Nursing Education, 60(5), 259-264. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20210420-04

Holbeck, R., & Hartman, J. (2018). Efficient strategies for maximizing online student satisfaction: Applying technology to increase cognitive presence, social presence, and teaching presence. Journal of Educators Online, 15(3), 1-5. https://doi:10.9743/jeo.2018.15.3.6

Kolil, V. K., & Achuthan, K. (2024). Virtual labs in chemistry education: A novel approach for increasing student’s laboratory educational consciousness and skills. Education and Information Technologies, 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12858-x

Lin, X., Huang, M., & Lin, Q. (2024). Students’ expectations of instructors in face-to-face and online learning environments at a Chinese university. E-Learning and Digital Media, 21(2), 160-179. https://doi.org/10.1177/204275302311564

Lux, G., Callimaci, A., Caron, M., Fortin, A., & Smaili, N. (2023). COVID-19 and emergency online and distance accounting courses: A student perspective of engagement and satisfaction. Accounting Education, 32(2), 115–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2022.2039729

Martin, F., & Bolliger, D. U. (2022). Developing an online learner satisfaction framework in higher education through a systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 19, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-022-00355-5

Nasir, M. K. M. (2020). The influence of social presence on students’: Satisfaction toward online course. Open Praxis, 12(4), 485-493. https://doi:10.5944/OPENPRAXIS.12.4.1141

Natarajan, J., & Joseph, M. A. (2022). Impact of emergency remote teaching on nursing students’ engagement, social presence, and satisfaction during COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing Forum, 57(1), 42-28. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12649

National Center for Education Statistics. (2023). Undergraduate enrollment. Condition of education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cha.

Nussli, N., Oh, K., & Davis, J. P. (2024). Capturing the successes and failures during pandemic teaching: An investigation of university students’ perceptions of their faculty’s emergency remote teaching approaches. E-Learning and Digital Media, 21(1), 42-69. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12649

O’Conner, S. (2024). Nursing students’ engagement in online learning. British Journal of Nursing, 33(13), 630-634. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2023.0161

Queen, C. (2022). Applying charismatic leadership to support learner engagement in virtual environments: Teaching and learning in a time of crisis. Pedagogy in Health Promotion, 9(3), 158-160. https://doi.org/10.1177/23733799221107613

Radović, S., Hummel, H. G., & Vermeulen, M. (2023). The mARC instructional design model for more experiential learning in higher education: Theoretical foundations and practical guidelines. Teaching in Higher Education, 28(6), 1173-1190. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1872527

Ravichandran, R. R., & Mahapatra, J. (2023). Virtual reality in vocational education and training: challenges and possibilities. Journal of Digital Learning and Education, 3(1), 25-31. https://doi.org/10.52562/jdle.v3i1.602

Roque-Hernández, R. V., Díaz-Roldán, J. L., Mendoza, A. L., & Salazar-Hernández, R. (2023). Instructor presence, interactive tools, student engagement, and satisfaction in online education during the COVID-19 Mexican lockdown. Interactive learning environments, 31(5), 2841-2854. https://doi:10.1080/10494820.2021.1912112

Schueler, B. E., & West, M. R. (2023). How online learning can engage students and extend the reach of talented teachers: evidence from a pandemic-era national virtual summer program. Journal of Educational Change, 24(4), 759-803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-022-09464-4

Shi, C., Diamond, K., & Smith, M. (2023). Different grouping methods in asynchronous online instruction: Social presence and student satisfaction. TechTrends, 1(67), 637-647. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-023-00876-4

Sun, J. C., & Rueda, R. (2012). Situational interest, computer self-efficacy, and self-regulation: Their impact on student engagement in distance education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(2), 191-204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01157.x

Tiwari, C. K., Bhaskar, P., & Pal, A. (2023). Prospects of augmented reality and virtual reality for online education: A scientometric view. International Journal of Educational Management, 37(5), 1042-1066. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-10-2022-0407

Vairamani, A. D. (2024). Enhancing social skills development through augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) in special education. Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality in Special Education, 65-89. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781394167586.ch3

Yang, D., Sinha, T., Adamson, D., & Rose, C. P. (2013, December). Turn on, tune in, drop out: Anticipating student dropouts in massive open online courses. In Proceedings of the 2013 NIPS Data-driven education workshop (pp. 1-8).