Abstract

This action research study evaluated and enhanced the Program Curriculum Deep Dive (PCDD) process to improve a bachelor’s degree program in healthcare administration at a private online college. Using a mixed-methods approach combining document analysis and a stakeholder survey, researchers examined cross-functional collaboration between academic and industry experts to modernize course content. Analysis revealed four key findings: (1) participants valued structured process organization; (2) personalized, collaborative support contributed to meaningful stakeholder engagement; (3) faculty perceived their contributions as instrumental in enhancing industry-curriculum alignment; and (4) faculty believed their curriculum changes resulted in improved student career preparedness. The study's systems thinking framework emphasized the interconnected nature of curriculum elements, while the action research methodology facilitated continuous improvement through iterative cycles of planning, implementation, and reflection. This research addresses the critical need for healthcare administration programs to bridge the preparation-practice gap through authentic learning experiences while navigating the unique challenges of online education. Recommendations include maintaining collaborative structures, emphasizing real-world applications, diversifying assignments for skill development, and documenting successful processes for institutional replication.

Keywords: curriculum development, course review, higher education, action research

Introduction

The growth in distance education, widely acknowledged as a “disruptive innovation” (Altmann et al., 2018; Snow Andrade, 2020; Thompson, 2016), presents unique challenges for institutions striving to balance academic rigor with flexible degree pathways. A framework developed by Diep et al. (2019) specifically addresses the needs of adult online learners, emphasizing several key elements in curriculum design. Their research underscores the value of authentic assignments that connect to real-world applications, intellectually challenging coursework paired with targeted support systems, meaningful peer collaboration opportunities, and diverse learning approaches that foster student autonomy. As institutions expand their program offerings to include more online options, structured and research-based evaluation processes become essential to ensure these design elements are effectively and consistently implemented across all courses. Structured evaluation processes support consistent review and revision of programs to identify strengths and weaknesses and make consistent improvements (Debataz, 2024).

This action research study aimed to systematically evaluate and enhance the Program Curriculum Deep Dive (PCDD) process used to improve a bachelor’s degree in healthcare administration program at a private online college. The research focused on assessing the effectiveness of cross-functional collaboration between academic and industry experts in modernizing course content and ensuring alignment with current healthcare industry needs. Through a comprehensive analysis of the PCDD, this study identified program strengths and areas for improvement while providing valuable insights into effective methods for maintaining academic program relevance in the rapidly evolving healthcare sector. The research is particularly timely given the increasing demand for online education among adult learners and the critical need for healthcare administrators to be well-prepared to address contemporary industry challenges.

The following research questions guided the study:

RQ1: What aspects of the Program Curriculum Deep Dive process were most instrumental in identifying and implementing healthcare curriculum revisions?

RQ2: How do stakeholders perceive their contributions to healthcare curriculum revisions?

Literature Review

Quality Assurance Frameworks in Higher Education

To maintain accreditation and uphold the same caliber of programs, universities must “show commitment to achieving a level of excellence comparable to the quality, integrity, student support, and effectiveness evident in their traditional campus instruction” (Nworie & Charles, 2021, para. 29). When evaluating the quality of distance education, many institutions rely on pre-existing standards established by various organizations such as Quality Matters (QM) or the Anthology Exemplary Course Rubric (Anthology, 2023).

The selection of appropriate evaluation tools is critical for quality assurance. Lowenthal et al. (2021) conducted a comparative study of the six most widely used course rubrics, specifically examining how effectively each addressed accessibility. On a 10-point scale, Quality Matters (QM) scored 7.5, while Blackboard Exemplary Course Program (ECP, now Anthology) scored 6. These differences underscore the importance of selecting a tool that aligns with an institution's academic priorities and values, particularly when accessibility is a key concern. While systems designed to evaluate individual courses often differ from those used for comprehensive program evaluation, the two must align to ensure cohesive and practical improvements. Some applicable frameworks for broader program assessment include the Online Learning Consortium's Quality Scorecard (OLC, 2024), the American Association for Higher Education’s Nine Principles of Good Practice for Assessing Student Learning (AAHE, 1992), and the CIPP (Context, Input, Process, Product) Evaluation Model (Stufflebeam, 2003).

Healthcare Administration: Unique Challenges and Requirements

The rapidly evolving healthcare field demands continuous adaptation of healthcare administration curricula to ensure that graduates are sufficiently prepared to meet industry challenges. Healthcare education requires industry partnerships, systematic curriculum reviews, and evidence-based teaching methods that prepare students for clinical practice (Saifan et al., 2021). A persistent challenge in healthcare education is the preparation-practice gap, where healthcare administrators report significant disparities between educational competencies and workforce demands (Hickerson et al., 2016). For example, only 23% of new nursing graduates possess entry-level competencies, and many patient safety errors stem from ineffective clinical judgments (Billings, 2019). Similar workforce gaps have been identified in specialized areas such as dementia training and care (Weiss et al., 2020) and pain treatment disparities (Meghani et al., 2012).

To address these gaps effectively, health educators must offer learning activities that engage students in real-world situations, challenging and nurturing their critical thinking skills (Crownover et al., 2024). Pedagogical approaches such as simulations, case studies, and data analyses provide authentic, career-relevant opportunities to better prepare students for the complexities of healthcare administration. This experiential learning focus is particularly significant in distance learning environments, where creating meaningful, practical experiences requires innovative approaches.

Academic and Industry Collaboration

The complexity of modern healthcare administration necessitates a collaborative approach to curriculum development that combines academic expertise with industry insight. Social accountability is emphasized in healthcare education, solidifying the connection between stakeholders in academia and the healthcare field (Belita et al., 2020). Such partnerships have significant potential to enhance community-engaged curricula and improve student satisfaction and engagement. Higher education institutions and industry partners complement each other by combining academic research skills with practical applications to enhance patient care (Sathian et al., 2023). This collaboration is particularly crucial for online healthcare programs that meet public healthcare needs and reach large audiences (Chen et al., 2019).

Factors contributing to successful academic-industry initiatives include positive leadership, empowerment of all stakeholders, a sense of ownership, and a culture of equality (Belita et al., 2020). Diverse communication modes, active listening, and encouragement by facilitators or leaders help promote meaningful participation. Stakeholders felt that they made valuable contributions when their expertise and feedback were formally acknowledged and integrated into decisions that led to critical changes or project development.

Approaches to Curriculum Program Reviews

Quality assurance activities in higher education, particularly program reviews, reveal a distinct divide in approach and purpose. Traditional reviews are typically managed by quality assurance offices and administrators with accountability-focused agendas. In contrast, more innovative approaches emphasize educational development, faculty autonomy, and continuous quality improvement through collaborative processes and learning communities. Numerous studies of curriculum review and revision processes highlight the need for institution-wide approaches to change, rather than course- or department-level impetus (Kandiko Howson & Kingsbury, 2021; Riad, 2022; Snow Andrade, 2020). This broader perspective helps ensure coherence across programs and alignment with institutional goals while respecting disciplinary expertise.

A key factor in a successful curriculum review is the strategic alignment of authority and expertise. Kang et al. (2020) demonstrated this concept in their study of an engineering department at a Hispanic-serving institution, where they applied Kotter's change model. Their success hinged on forming a stakeholder team that balanced faculty expertise with authority while leveraging the department chair's credibility to manage disciplinary hierarchies effectively. Similarly, Lock et al. (2018) emphasized the importance of involving stakeholders at various levels. They found that institutional leaders could envision the curriculum from a broader perspective, including the overall academic vision, student employability trends, and institutional strengths. Various stakeholder perspectives complemented the instructors' ability to identify and define relevant course themes, teaching practices, and assessment strategies.

The collaborative nature of curriculum review emerges as critical for meaningful reform. Oliver and Hyun (2011) found that shared decision-making and a common philosophical foundation were essential in overcoming the complexities of institutional change during a four-year curriculum review process. In a similar approach, Hoare et al. (2023) proposed the Program Review Learning Community (PRLC) model to guide the program review process through an appreciative lens. They acknowledged that those who volunteered to participate in and complete the review possess the theoretical and experiential knowledge necessary to move the process forward.

Online College Curriculum Review: Processes and Challenges

Curriculum reviews in fully online colleges remain underexplored in the academic literature, despite their critical importance for ensuring quality education in digital environments. A comprehensive review process involves critically examining course content and structure, assessing quality and relevance, ensuring alignment with learning outcomes, and evaluating the effectiveness of the online learning experience against industry standards. Online programs demand additional considerations, including accessibility features, interactive elements, and adherence to legal guidelines such as copyright ownership (Hai-Jew, 2010). A consistent course structure across the program of study helps establish clear expectations and fosters stronger online learning communities (Shea et al., 2016).

Recent studies have focused on enhancing student engagement and learning experiences through course redesign. Sheridan and Gigliotti (2023) and Duck and Stewart (2021) undertook systematic course redesigns in sociology and pathophysiology to improve student learning outcomes. While Sheridan and Gigliotti applied a Universal Learning Design framework to enhance engagement and navigation across multiple campuses, Duck and Stewart focused on accommodating diverse learning styles through the use of active learning strategies. Both studies revealed important online course design considerations relevant to course reviews. Sheridan and Gigliotti emphasized peer collaboration and theory-practice connections, while Duck and Stewart highlighted instructional resources required to support active learning approaches, particularly for providing timely feedback and assessment.

For online healthcare administration programs specifically, the literature suggests that successful curriculum reviews must address the preparation-practice gap through authentic learning experiences, incorporate industry perspectives through structured collaboration, and attend to the unique aspects of online learning environments. However, more research is needed on comprehensive program reviews in fully online colleges, as much of the current literature focuses on individual course redesign rather than program-level evaluation.

Theoretical Framework

The systems thinking framework views education as a complex, interconnected system in which curriculum, instruction, assessment, institutional goals, and external standards interact and influence one another. This framework focuses heavily on the big picture and how different aspects of the curriculum come together to create the whole (Shaked & Schechter, 2019). Changes in one part of the system create ripple effects across other areas, requiring continuous adaptation and improvement. Curriculum mapping is a powerful tool for adopting this holistic perspective by systematically visualizing relationships among courses, learning outcomes, and assessment methods. The principle of interconnectedness acknowledges that curricular elements do not exist in isolation but are part of a broader system where they mutually influence one another (Sweeney & Meadows, 2010).

Another critical aspect is continuous adaptation. Curriculum mapping supports this cyclical model of evaluation and improvement, moving beyond a one-time exercise to become an integral part of the institution's strategic planning and development processes. Senge (2006) emphasized this point by advocating for processes of change rather than short-term solutions, noting that educational systems must continuously evolve to meet changing demands.

Moreover, systems thinking emphasizes both multiperspective engagement and data-driven decision-making in curriculum review. By incorporating diverse stakeholder input—including faculty, students, industry partners, and accrediting bodies—institutions can ensure their curricula remain aligned with evolving learning objectives, industry needs, and external standards (Capra & Luisi, 2014). The insights generated from curriculum mapping provide a robust foundation for evidence-based changes to courses, learning outcomes, and assessment methods. By leveraging data in this way, institutions can make informed decisions that enhance the quality and effectiveness of their educational offerings while maintaining a holistic view of the curriculum system and aligning with broader organizational development principles for effective institutional change (Senge & Sterman, 1992; Senge et al., 2012).

Methodology

Action research operates through a cyclical process of planning, implementing actions, and conducting research to determine effects (Lewin, 1946). Action researchers address challenges through systematic planning, data collection, reflection, and informed action (Burns, 2015). Susman and Evered (1978) formalized a five-stage approach, emphasizing that "the researcher is necessarily a part of the data he or she helps to generate" (p. 600), highlighting this methodology's participatory nature, in which researchers actively engage with their context.

In higher education curriculum design, action research offers a reflective process emphasizing stakeholder collaboration to enhance educational practices (Davison et al., 2021). It enables educators to systematically investigate instructional strategies, course content, and assessment methods, providing insights into student engagement and learning outcomes. Numerous higher education studies have documented the value of action research in enhancing student engagement through reflective practice and stakeholder empowerment (Gibbs et al., 2017; McGahan, 2018). By adopting this methodology for curriculum review, institutions create a responsive approach to maintaining curriculum quality while addressing the specific challenges of online healthcare administration education.

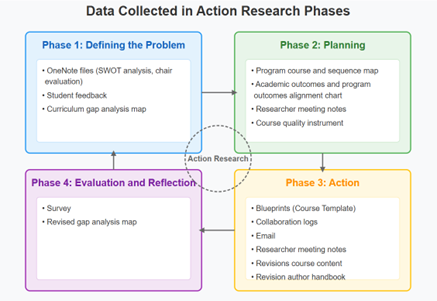

The action research study followed a structured four-phase approach outlined in Table I, which guided both the curriculum revision process and our research activities.

Research Setting and Population

This study was conducted at a four-year, private online college offering approximately 80 degree programs at both undergraduate and graduate levels across healthcare, nursing, education, business, and leadership disciplines. The institution primarily serves non-traditional students, with 91% of its student population aged 25 or older. The demographic composition reflects a predominantly female enrollment (78%) compared to male students (22%). The student body's ethnic diversity includes 48% White, 21% Black or African American, 16% Hispanic/Latino, 6% Asian, and 9% identifying as two or more races, other, or international students (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2023). This diverse population primarily consists of working professionals seeking to advance their careers through higher education while balancing their professional and personal responsibilities.

Table I

Timeline of Research Cycle

| Phase | Time | Process | Participants |

Phase 1: Defining the Problem | April-June 2024 |

| Academic Provost Assistant Provost Director of Assessment Department Chair Curriculum & Development Leader and Specialists |

Phase 2: Planning | July-August 2024 |

| Assistant Provost Department Chair Faculty SMEs Curriculum & Development Specialists |

Phase 3: Action | September-November 2024 |

| Department Chair Faculty SMEs Curriculum & Development Team |

Phase 4: Evaluation and Reflection | December 2024-March 2025 |

| Department Chair Faculty SMEs Curriculum & Development Leadership and Specialists |

Data Collection Methods

Data were collected through two complementary methods: a comprehensive document review and an anonymous survey of PCDD participants. In the document review, existing PCDD documentation and related materials were analyzed. To maintain focused inquiry, researchers examined curriculum development and process evaluation content. Artifacts included student and faculty satisfaction survey feedback, a curriculum map with gap analysis, administrative documentation, revision training course materials, collaboration logs and email communication between curriculum developers and SMEs, course quality assessment rubrics, and revised course blueprints showing the implementation of changes.

The second component involved developing a survey instrument aligned with the research questions (Appendix A). This survey was peer-reviewed before distribution to participants via an online platform. The survey was sent to ten key stakeholders in the curriculum review process, including a department chair, seven faculty subject matter experts (SMEs), and two curriculum and production department leaders. The response rate was 70%, representing all participant sub-groups. Participants reported sixteen or more years of experience in the healthcare industry and/or healthcare education, with expertise in behavioral health, regulatory compliance, medical genetics, nutrition, nursing, gerontology, finance, and administration.

Defining the Problem

The PCDD process began with executive leadership analyzing multiple data sources, including market analyses, graduate surveys, student satisfaction metrics, and program viability assessments. The department chair conducted a SWOT analysis of the program, confirming the relevance of the curriculum. This analysis identified several program strengths, including the asynchronous online format, as well as areas requiring attention to maintain industry alignment.

The gap analysis process involved systematically comparing existing program content against current industry standards and emerging healthcare priorities. Specifically, the team examined:

- Job market data, position descriptions, and skills forecasts for healthcare administrators to identify required competencies

- Recent graduate and alumni feedback regarding preparedness for workplace challenges

- Professional healthcare standards from organizations such as the Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Management Education (CAHME)

- Current literature on healthcare administration trends and workforce needs

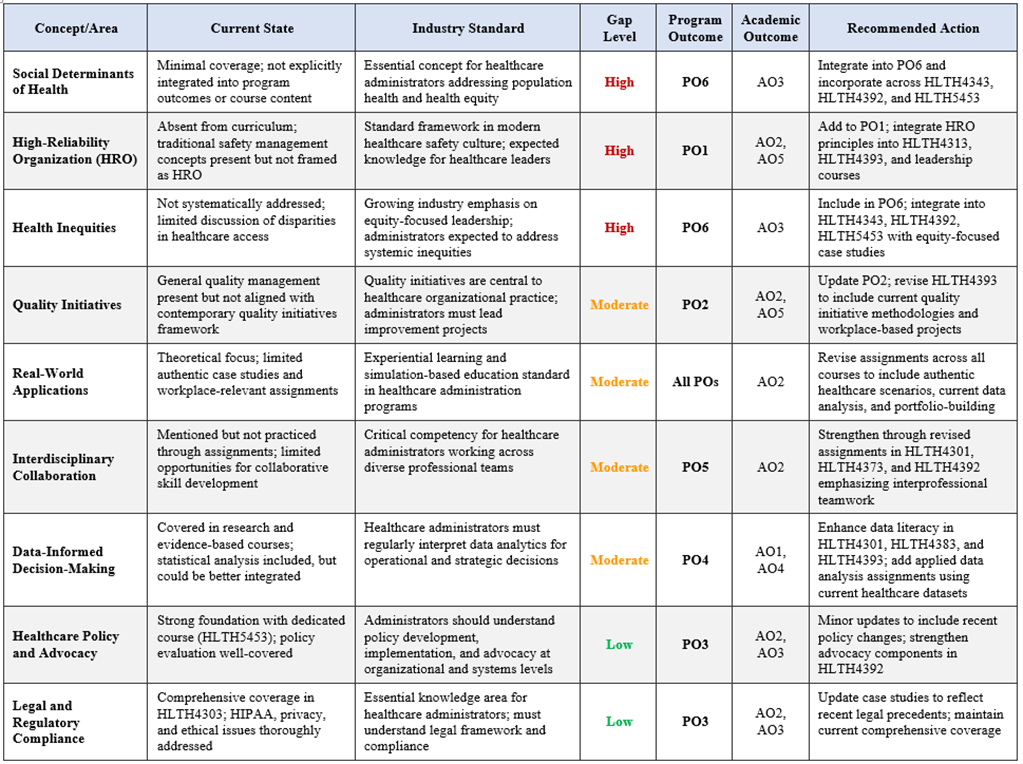

A detailed curriculum mapping matrix was used to systematically assess each course against institutional program and academic outcomes and determine critical gaps (See Appendix B for gap analysis summary). The existing curriculum inadequately addressed contemporary healthcare concepts that had gained prominence in recent years. For instance, while the program covered traditional quality management, it did not explicitly incorporate "quality initiatives" as they are currently framed in modern healthcare organizations. Similarly, the curriculum lacked explicit coverage of "social determinants of health," a concept increasingly recognized as essential for healthcare administrators addressing population health and health equity. The terminology "high-reliability organization"—now standard in healthcare safety culture—was absent from course content. Additionally, "health inequities" and strategies to address them were not systematically integrated into the curriculum, despite growing industry emphasis on equity-focused leadership.

Following this gap identification, the program description was systematically revised to ensure alignment with the learner profile, market needs, industry best practices, and institutional goals. Program outcomes were updated to incorporate emerging industry terminology and concepts, and course titles and descriptions were modified to enhance clarity and relevance.

Planning

After identifying industry gaps, the curriculum team selected qualified subject matter experts to review each program course using a course quality instrument based on the Quality Matters standards. A program mapping analysis was conducted to visually display data relationships between courses, learning outcomes, assessment methods, and curriculum. All program courses were mapped according to their outcomes, objectives, key understandings, and alignment with institutional academic outcomes and the Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Management Education competencies framework (CAHME, 2025):

- Knowledge of the healthcare system

- Communications and interpersonal effectiveness

- Critical thinking, analysis, and problem-solving

- Management and leadership

- Professionalism and ethics

A curriculum team member reviewed each course carefully to assess the level of learning of key course concepts, determining if they were introduced, practiced, or demonstrated. New concepts and skills identified during Phase 1 as critical for student learning were systematically incorporated into objectives and assignments for revision courses. To ensure inter-rater reliability, a peer reviewer also completed a map, noting a high level of agreement between assessments.

Take Action

Faculty SMEs were surveyed to identify areas of expertise and matched to specific subjects based on their backgrounds. Each SME completed curriculum revision training that provided best practices for online course design, access to the course author handbook, and instructions on effectively using tools, templates, academic databases, and other resources. Research consistently shows that quality online course design and clear organization increase student motivation, learning, and retention (Joosten & Cusatis, 2019; Muljana & Luo, 2019). The SMEs and curriculum development team reviewed course evaluation feedback and determined how changes in healthcare practices could be incorporated to create more relevant and meaningful student assignments. To guide this review process, they addressed several key questions, including:

- Have legal guidelines and relevant policies changed? (intellectual property, accessibility compliance with WCAG standards, learner privacy)

- What progress or change in the field might inform the course revision? (in-field practices, new data sources, professional codes of ethics)

- What updates in teaching and learning methodologies might be relevant? (sequencing, learner-centered experiences, career-relevant tasks)

- What updates in relevant technologies could improve the course? (new discussion platform with video response; student digital projects)

Accessibility was systematically addressed throughout the revision process. The curriculum development team reviewed all SME-created materials and formatted them in accordance with established accessibility guidelines. For multimedia components such as videos, instructional designers conducted accessibility verification, including checking caption accuracy and ensuring audio description was available where appropriate. This multi-level review process ensured that revised courses met institutional accessibility standards and provided equitable learning experiences for all students.

Course revision recommendations emphasized authentic case studies, real-time healthcare data utilization, and quality improvement initiatives similar to workplace initiatives. SMEs were provided with a template to guide their revision. Consistency in online course templates has been found to ease the collaborative curriculum development process and increase student engagement, as it fosters familiarity with content presentation (McMullan et al., 2022). A cloud-based file management system facilitated the collaborative revision process, allowing the SME and curriculum development team members to work on course materials simultaneously.

Evaluate and Reflect

While each phase of the action research study initially involved collecting and analyzing data in isolation, the final evaluation stage demanded a comprehensive integration of all data points. This holistic review allowed us to examine how individual data elements collectively informed the program curriculum revision process. This review revealed interconnections that might have remained hidden when examining each phase separately. Figure I illustrates the data collection points across the study phases.

Researchers systematically reflected on the empirical data and their experiences, examining contextual factors, underlying assumptions, critical decision points, and implementation challenges.

Figure I

Data Collection by Action Research Phase

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using Braun and Clarke's (2022) six-step thematic analysis framework. Both researchers independently familiarized themselves with the data by carefully examining collaboration logs, email communications, SME rating instruments, curriculum mapping analysis, and open-ended survey responses, documenting initial observations and analytical insights. Following the familiarization, each researcher systematically coded relevant data segments using meaningful descriptive labels. The researchers then met to compare codes and discuss discrepancies, reaching consensus through dialogue and re-examination of the data. The third step involved collaboratively generating preliminary themes by clustering similar codes while preserving nuanced meanings. Theme development and review followed, wherein both researchers examined coded data within each grouping to verify internal cohesion before consolidating into comprehensive thematic categories. The fifth step involved refining, defining, and naming themes through iterative discussion and mutual agreement. Finally, researchers produced a written analysis, organizing findings by salience and alignment with research questions.

Quantitative survey data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and integrated with the qualitative findings to provide a comprehensive understanding of the effectiveness of the PCDD process. The triangulation of data from multiple sources helped establish trustworthiness.

Findings

RQ1: Process Effectiveness

Research question one examined what aspects of the Program Curriculum Deep Dive process were instrumental in identifying and implementing healthcare curriculum revisions. Thematic analysis revealed two prominent findings: stakeholders valued the process organization and appreciated personalized support.

Structured Process Organization

Participants consistently highlighted the value of well-organized processes and robust support structures during the revision cycle. Implementing structured project management workflows was central to ensuring consistent progress throughout development. The course quality instrument and curriculum map provided clear records of decisions, ensuring consistency and continuity. Early in the revision cycle, course-specific feedback identified precise needs for each course, which were addressed later in the revision process.

One participant described the structured approach: "...you had a training first and then you followed the map. I didn't feel as if there were any gaps or as if I was left out on my own. You were supported throughout the whole process."

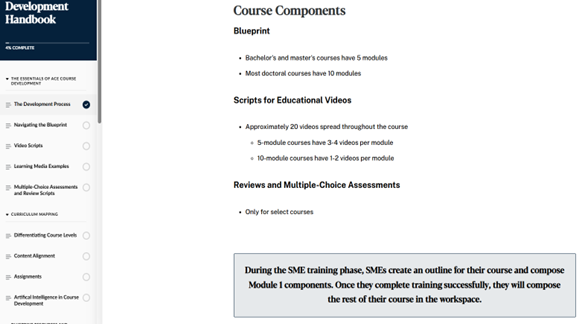

Enrollment in course revision training prepared subject matter experts before initiating their work. This training incorporated methodological guidance and concrete tools for curriculum development, including a handbook with guidelines for addressing every aspect of curriculum development. Figure II visually represents a required training module completed before the revision begins.

The collaboration log documented ongoing communication, supporting continuous improvement. Initial communication established clear expectations, as evidenced by this collaboration log entry:

"Thanks for meeting today. As a summary, all your materials are located in the [workspace] here: HLTH4393 Quality Management for Healthcare Administrators. I'll send a meeting invite for next Wednesday at 1:00 pm to review your progress and provide any guidance needed. In the meantime, feel free to contact me here or through email with any questions. I look forward to working with you on this course!"

These structured and scheduled check-ins allowed for real-time adjustments to the workflow and created accountability within the process. One participant noted: "Using the program map and the collaboration log to ask questions ensures you're on the right path and were invaluable tools."

Figure II

Training Module Example

Personalized Collaborative Support

Key to the success of this process was personalized support. Specific assistance tailored to each participant's needs emerged as a unique theme during data analysis. This precedence of personalized work was set early in the process when the curriculum development team matched each course revision with a SME whose education, expertise, and professional experience aligned best. This approach enabled SMEs to contribute their knowledge where it would have the most significant impact.

Participants valued one-on-one meetings with a curriculum development team member and ongoing communication in the collaboration logs. One stakeholder reflected: "Overall, I found this to be an excellent process and I appreciated the real-time collaboration between the SMEs and the curriculum developer." The collaboration logs enabled SMEs with demanding schedules to receive asynchronous support, allowing them to contribute to the course blueprint when their professional responsibilities permitted:

"Hi [CD team member]. I just completed the blueprint. Will you take a look at Step 3 on Module 3 assignment to see if this works? Thank you for all of your help!"

"Sounds great, [CD team member]! I will get to these items later this afternoon. Please proceed with drafting the assignments and I will search for or draft a case study for M5. Thank you!"

Within the survey, all SMEs (n = 5) unanimously rated the value of this collaborative approach as the highest level (5 out of 5) on the effectiveness scale, underscoring the critical importance of this partnership in curriculum development. The openness to growth and feedback was evident in this collaboration log comment: "[CD team member] Thanks! Module 1 Part 3 is ready, but I need to update the others, mostly for the direct quotes. If there is anything you would like me to change based on the first one, I can apply that feedback."

RQ2: Stakeholder Perceptions

Research question two explored how stakeholders perceive their contributions to healthcare curriculum revisions. The emerging themes indicated that stakeholders felt their contributions helped align the curriculum with current industry standards and better prepare students with the skills for professional success.

Industry-Curriculum Alignment

Notably, all SME survey participants (n = 5) felt that their contributions directly impacted curriculum improvements and led to the integration of more current industry practices. When evaluating the overall impact of industry-relevant modifications, all SMEs assigned the highest possible rating (5 out of 5).

The curriculum revision process addressed identified gaps between theory and professional practice. SMEs provided critical insight into current healthcare trends, technologies, and regulatory requirements. One participant explained: "Using SMEs to help with revisions and incorporating more real-world examples and drafting assignments to emulate actual work in healthcare helps the student understand the theoretical underpinnings while developing skills." Another participant noted, "It seems students will be able to apply what they learn in class immediately in their careers."

The collaboration resulted in assignments that more closely mirror industry practices, including developing codes of ethics for healthcare facilities, creating social media policies, analyzing complex ethical case studies, and crafting professional communications for various stakeholders.

Student Career Preparedness and Skill Development

Research participants felt their contributions would directly influence students' experience in the course and develop job-ready skills. One SME shared: "Actually doing the work of a manager/leader in healthcare. Helps students identify what obstacles they may face in new roles."

Respondents emphasized the role their input had in integrating more applicable workplace scenarios and assignments, which they felt "should drive student interest, which should increase impact." These opportunities to practice responding to real-world healthcare issues allow students to learn and grow in a low-stakes setting before facing the pressure and responsibilities of their future careers.

Course revisions empower students to create a professional portfolio through assignments where they create a personal leadership philosophy, resume, and cover letter and practice writing professional articles. One participant observed: "Adding in the resume and cover letter will help the student to begin to think about looking for that healthcare job... but to also start thinking about where they see themselves when they complete their degree."

Students can apply critical thinking to make sound ethical decisions through simulated work experiences, such as a case study on end-of-life issues and a budget analysis to recommend expanding mental health services. One survey respondent noted: "The revised curriculum incorporated more critical thinking opportunities for students using real-world healthcare examples. I think this is one of the best improvements in the new courses."

Discussion

The Program Curriculum Deep Dive (PCDD) process exemplifies effective curriculum development principles, emphasizing strong leadership, structured workflows, and precise documentation (Bens et al., 2021). Consistent progress was facilitated by structured project management, while course quality instruments and curriculum mapping provided clear decision records, supporting Shaked and Schechter's (2019) holistic view of curriculum integration. The emphasis on change processes, rather than quick fixes, aligned with Senge’s (2006) systems thinking framework.

Collaborative Curriculum Development: Processes and Partnerships

A critical component of this success was integrating SME professional knowledge with the curriculum development team's pedagogical expertise. This partnership generated value by combining theoretical research skills with practical applications (Sathian et al., 2023). Matching SME expertise to specific courses maximized the impact of their contributions, supporting research on balanced stakeholder teams in curriculum review (Kang et al., 2020; Lock et al., 2018). Institutional leaders provided the broader curriculum perspective to complement instructors' course-specific insights.

Stakeholder Engagement and Continuous Improvement

Pre-revision training and documentation supported continuous improvement, aligning with research demonstrating enhanced application of design principles when instructors have access to best practices during the editing process (Corral et al., 2018). Multiple feedback mechanisms enabled responsive adjustments to emerging needs, supporting research on the importance of diverse communication methods and active listening in fostering participation (Belita et al., 2020). The process also addressed Oliver and Hyun's (2011) observation that overcoming institutional change complexities requires shared decision-making and unified philosophical foundations.

Enhancing Student Career Preparedness and Skill Development

The curriculum revisions transformed theoretical content into practical learning experiences, addressing a fundamental need in healthcare education for industry partnerships, systematic curriculum reviews, and evidence-based teaching methods (Saifan et al., 2021). Stakeholders' contributions of authentic workplace scenarios aligned with research emphasizing real-world applications in developing job-ready skills (Crownover et al., 2024; Diep et al., 2019). Integrating professional portfolio elements enhanced student career readiness, while the overall course design improvements supported increased student motivation, learning, and retention (Joosten & Cusatis, 2019). Simulated work experiences directly addressed concerns regarding ineffective clinical judgments by providing structured opportunities for critical thinking and ethical decision-making (Billings, 2019).

Systems Thinking and Sustainable Engagement

The structured processes and personalized support facilitated effective alignment between industry and curriculum, demonstrating the principle of interconnectedness in practice (Capra & Luisi, 2014). Applying systems thinking through action research emphasizes experiential learning and meaningful participant involvement (Coghlan & Brydon-Miller, 2014). Sustained engagement and capacity building emerged through consistent and authentic participation, supporting Belita et al.'s (2020) emphasis on influential leadership and balanced power dynamics. This multi-perspective engagement exemplified systems thinking principles (Senge, 2006), while participation fostered deep reflection and resulted in a replicable framework for future program revisions.

Ethical Considerations

The study maintained rigorous ethical standards throughout its implementation. Following IRB approval, researchers emailed participants comprehensive information about the study's purpose, methods, and potential impacts. The voluntary nature of participation was emphasized, including the right to withdraw at any time. Informed consent was obtained through an electronic process prior to survey completion. Participant confidentiality was maintained through the use of anonymous survey links and pseudonyms in all research documentation. Data security measures included storage in a password-protected cloud drive accessible only to the two researchers. Access to institutional data, including faculty and student satisfaction survey results, was restricted to authorized leaders and curriculum department members through secure, password-protected files.

Conclusions and Implications for Higher Education

Distance learning, once seen primarily as a niche feature of open universities, has evolved into a mainstream educational approach with the power to revolutionize how we structure and deliver education. These changes extend beyond the delivery method to create opportunities for comprehensive curriculum revisions informed by assessment findings and evolving employer needs. The study’s quality assurance process emphasized two key elements: (1) collaborative curriculum review and mapping processes focused on continual improvements and (2) enhancement of the student experience.

Implications for Practice

Analysis of the data revealed several critical implications for practice. First, institutions should maintain a collaborative process structure, including training, mapping, and regular communication touchpoints that have proven effective. Second, curriculum development should continue emphasizing real-world applications through SME involvement and authentic scenarios. Third, assignment diversification is needed to enhance student engagement and practical skill development. Fourth, the highly effective personalized support curriculum developers provide should be recognized and replicated in future iterations.

Operational recommendations include combining initial SME training with completing the first course module to set clear expectations and establish standard timelines based on estimated work percentages for each course. This adjustment addresses feedback from one SME who requested additional time for the course revision. Successful process elements should be documented to ensure replication in both ongoing practices and formal curriculum revisions across the institution.

Limitations

Several limitations warrant acknowledgment. The dual role of researcher-participant introduced potential bias in data collection, interpretation, and reporting of results. To mitigate this, we implemented collaborative checkpoints and regular peer debriefing sessions where team members critically questioned each other's assumptions and interpretations of the data. This process helped broaden our analytical perspective. Our triangulation approach incorporated multiple data sources, strengthening the validity of our conclusions. One researcher maintained a distance from direct SME interactions to provide additional objectivity. While research studies typically face limited generalizability due to their context-specific nature, we documented our methods with deliberate transparency to resonate with other practitioners and support their implementation efforts.

Recommendations for Future Research

Several key areas warrant further investigation to build upon this study's findings. A longitudinal impact assessment is crucial for understanding the sustained effectiveness of curriculum revisions by tracking student performance metrics in revised courses compared to previous versions, analyzing alumni success post-graduation, and examining employer feedback on graduate preparedness. Future research should also examine the scalability and transferability of the PCDD process across different academic disciplines and institutional contexts. These future research directions emphasize both practical implementation and theoretical advancement while focusing on continuous improvement in healthcare education.

References

Altmann, A., Ebersberger, B., Mössenlechner, C., & Wieser, D. (2018). Introduction: The disruptive power of online education: Challenges, opportunities, responses. In A. Altmann, B. Ebersberger, C. Mössenlechner, & D. Wieser (Eds.), The disruptive power of online education (pp. 1–4), Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-78754-325-620181001

American Association for Higher Education (AAHE). (1992). Nine principles of good practice for assessing student learning.

Anthology Inc. (2023). Anthology exemplary course program rubric. https://www.anthology.com/material/exemplary-course-program-rubric

Belita, E., Carter, N., & Bryant-Lukosius, D. (2020). Stakeholder engagement in nursing curriculum development and renewal initiatives: A review of the literature. Quality Advancement in Nursing Education, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.17483/2368-6669.1200

Bens, S., Kolomitro, K., & Han, A. (2021). Curriculum development: Enabling and limiting factors. International Journal for Academic Development, 26(4), 481–485.

Billings, D. E. (2019, April 16). Closing the education-practice gap. Wolters Kluwer. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/expert-insights/closing-the-educationpractice-gap

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage.

Burns, A. (2015). Action research. In J. D. Brown and C. Coombe (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to research in language teaching and learning (99–104). Cambridge University Press.

Capra, F. & Luisi, P. L. (2014). The systems view of life: A unifying vision. Cambridge University Press.

Chen, B. Y., Kern, D. E., Kearns, R. M., Thomas, P. A., Hughes, M. T., & Tackett, S. (2019). From modules to MOOCs: Application of the six-step approach to online curriculum development for medical education. Academic Medicine, 94(5), 678–685. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330735985_From_Modules_to_MOOCs_Application_of_the_Six-Step_Approach_to_Online_Curriculum_Development_for_Medical_Education

Coghlan, D., & Brydon-Miller, M. (Eds.) (2014). The SAGE encyclopedia of action research. (Vols. 1–2). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446294406

Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Education (CAHME). (2025). About us. https://cahme.org/about/

Corral, J., Post, M .D., & Bradford, A. (2018). Just-in-time faculty development for pathology small groups. Medical Science Education, 28, 11–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-017-0516-z

Crownover, J., Connolly, T. & Beaton, M. (2024). Bridging the preparation-practice gap. Nurse Educator, 49(2), E101–E102. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0000000000001549

Davison, R. M., Martinsons, M. G., & Malaurent, J. (2021). Research perspectives: Improving action research by integrating methods. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 22(3), 851–873. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00682

Diep, A. N., Zhu, C., Cocquyt, C., de Greef, M., Vo, M. H., & Vanwing, T. (2019). Adult learners’ needs in online and blended learning. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 59(2), 223–253.

Duck, A. A., & Stewart, M. W. (2021). A pedagogical redesign for online pathophysiology. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 16(4), 362–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2021.04.005

Gibbs, P., Cartney, P., Wilkinson, K., Parkinson, J., Cunningham, S., James-Reynolds, C., Zoubir, T., Brown, V., Barter, P, Sumner, P., MacDonald, A., Dayananda, A., & Pitt, A. (2017). Literature review on the use of action research in higher education. Educational Action Research, 25(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2015.1124046

Hai-Jew, S. (2010). An instructional design approach to updating an online course curriculum. Educause Quarterly, 33(4). https://er.educause.edu/articles/2010/12/an-instructional-design-approach-to-updating-an-online-course-curriculum

Hickerson, K., Terhaar, F. M., & Taylor, A. L. (2016). Preceptor support to improve nurse competency and satisfaction: A pilot study of novice nurses and preceptors in a pediatric intensive care unit. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 6(12), 57–62. http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v6n12p57

Hoare, A., Dishke Hondzel, C., Wagner, S., & Church, S. (2023). A course-based approach to conducting program review. Discover Education, 3(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-023-00085-4

Joosten, T., & Cusatis, R. (2019). A cross-institutional study of instructional characteristics and student outcomes: Are quality indicators of online courses able to predict student success? Online Learning, 23(4), 354–378. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v23i4.1432

Kandiko Howson, C., & Kingsbury, M. (2021). Curriculum change as transformational learning. Teaching in Higher Education, 28(8), 1847–1866. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1940923

Kang, S. P., Chen, Y., Svihla, V., Gallup, A., Ferris, K., & Datye, A. K. (2020). Guiding change in higher education: An emergent, iterative application of Kotter’s change model. Studies in Higher Education, 47(2), 270–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1741540

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues, 2(4), 43–46.

Lock, J., Hill, L., & Dyjur, P. (2018). Living the curriculum review: Perspectives from three leaders. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 48(1), 118–131. https://doi.org/10.7202/1050845ar

Lowenthal, P., Lomellini, A., Smith, C., & Great, K. (2021). Accessible online learning: An analysis of online quality assurance frameworks. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 22(2), 15–29.

McGahan, S. J. (2018). Reflective course review and revision: An overview of a process to improve course pedagogy and structure. Journal of Educators Online, 15(3), Article 3. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1199111.pdf

McMullan, T., Williams, D., Ortiz, Y. L., & Lollar, J. (2022). Is consistency possible? Course design and delivery to meet faculty and student needs. Current Issues in Education, 23(3). https://doi.org/10.14507/cie.vol23iss3.2092

Meghani, S. H., Polomano, R. C., Tait, R. C., Vallerand, A. H., Anderson, K. O., & Gallagher, R. M. (2012). Advancing a national agenda to eliminate disparities in pain care: Directions for health policy, education, practice, and research. Pain Medicine, 13(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01289.x

Muljana, P. S., & Luo, T. (2019). Factors contributing to student retention in online learning and recommended strategies for improvement: A systematic literature review. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 18, 19–57. https://doi.org/10.28945/4182

National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.) Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). U.S. Department of Education. https://nces.ed.gov/collegenavigator/

Nworie, J. & Charles, B. C. (2021). Quality standards and accreditation of distance education programs in a pandemic. Online Journal of Distance Learning Association, 24(3). https://ojdla.com/articles/quality-standards-and-accreditation-of-distance-education-programs-in-a-pandemic

Oliver, S. L., & Hyun, E. (2011). Comprehensive curriculum reform in higher education: Collaborative engagement of faculty and administrators. Journal of Case Studies in Education, 2. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1057195.pdf

Online Learning Consortium (OLC). (2024). Administration of online programs: OLC Quality Scorecard suite. https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/quality/scorecards/program-level/#download

Riad, J. (2022). Obstacles to successful curriculum management in higher education and opportunities for improvement. International Journal for Innovation Education and Research, 10(12), 89–93.

Saifan, A., Devadas, B., Daradkeh, F., Abdel-Fattah, H., Aljabery, M., & Michael, L. M. (2021). Solutions to bridge the theory-practice gap in nursing education in the UAE: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), 490. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02919-x

Sathian, B., van Teijlingen, E., Simkhada, P., Banerjee, I., Manikyam, H. K., & Kabir, R. (2023). Strengthening healthcare through academic and industry partnership research. Nepal Journal of Epidemiology, 13(2), 1264–1267. https://doi.org/10.3126/nje.v13i2.58243

Senge, P. M. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art & practice of the learning organization (Rev. ed.). Currency.

Senge, P. M., Cambron-McCabe, N., Lucas, T., Smith, B., & Dutton, J. (2012). Schools that learn (updated and revised): A fifth discipline fieldbook for educators, parents, and everyone who cares about education. Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Senge, P. M., & Sterman, J. D. (1992). Systems thinking and organizational learning: Acting locally and thinking globally in the organization of the future. European Journal of Operational Research, 59(1), 137–150.

Shaked, H., & Schechter, C. (2019). Systems thinking for principals of learning-focused schools. Journal of School Administration Research and Development, 4(1), 18–23.

Shea, J., Joaquin, M. E., & Wang, J. Q. (2016). Pedagogical design factors that enhance learning in hybrid courses: A contribution to design-based instructional theory. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 22(3), 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2016.12002254

Sheridan, L., & Gigliotti, A. (2023). Designing online teaching curriculum to optimise learning for all students in higher education. The Curriculum Journal, 34(4), 651–673. https://doi.org/10.1002/curj.208

Snow Andrade, M. (2020). A responsive higher education curriculum: Change and disruptive innovation. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.80443

Stufflebeam, D. L. (2003). The CIPP model for evaluation. In D. L. Stufflebeam & T. Kellaghan (Eds.), The international handbook of educational evaluation (Chapter 2). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Susman, G. I., & Evered, R. D. (1978). An assessment of the scientific merits of action research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23(4), 582–603.

Sweeney, L. B., & Meadows, D. (2010). The systems thinking playbook: Exercises to stretch and build learning and systems thinking capabilities. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Thompson, C. J. (2016). Disruptive innovation in graduate nursing education: Leading change. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 30(3), 177–179. https://doi.org/10.1097/NUR.0000000000000199

Weiss, J., Tumosa, N., Perweiler, E., Forciea, M. A., Miles, T., Blackwell, E., Tebb, S., Bailey, D., Trudeau, S., & Worstell, M. (2020). Critical workforce gaps in dementia education and training. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(3), 625–629. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16341

Appendix A

Survey Instrument

| Part I. Demographic Information | Item Type | Response Options |

| Multiple Choice | Healthcare Department Faculty or Chair Curriculum Developer Curriculum Department Leader Other [specify] |

| Multiple Choice | [0-5] [6-10] [11-15] [16-20] [21+] |

| Open Response |

| Part II. Collaboration and Process | |||||

| Please rate your agreement with the following statements using this scale: | Strongly Disagree (1) | Disagree (2) | Neutral (3) | Agree (4) | Strongly Agree (5) |

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| [Open response] | ||||

| Part III. Industry Alignment | |||||

| Please rate your agreement with the following statements using this scale: | Strongly Disagree (1) | Disagree (2) | Neutral (3) | Agree (4) | Strongly Agree (5) |

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| [Open response] | ||||

| [Open response] | ||||

| Part IV. Final Thoughts | |

| [Open response] |

| [Open response] |

Appendix B

Program Curriculum Gap Analysis Summary